APRA’s loan repayment deferral data: Shining a light on credit risk

As coronavirus hit, many banks started offering support packages to allow borrowers to defer their loan repayments for up to six months. To support banks’ efforts to help their customers, APRA granted concessionary capital adequacy treatment for eligible loans that had been granted temporary repayment deferrals due to COVID-19.

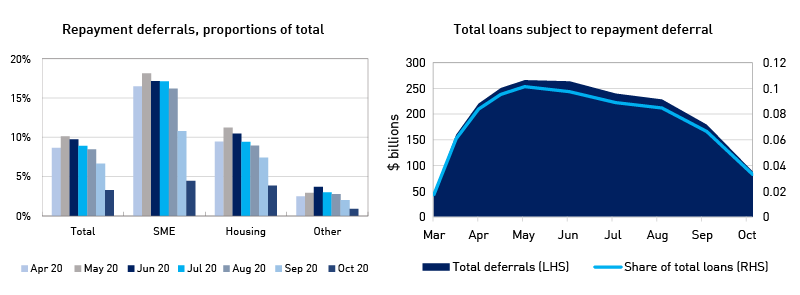

Essentially, APRA allowed banks and other authorised deposit-taking institutions, or ‘ADIs’ (such as credit unions or building societies), to ‘stop the clock’ on the counting of arrears. Normally, when a loan falls into arrears, APRA requires an ADI to hold more capital against that loan, because the loan is considered to represent a higher risk of loss. By not enforcing this approach for loans in arrears that remain on an eligible repayment deferral, APRA helped ADIs to work more effectively with their customers through this uncertain period (in essence, by lowering the financial cost of offering payment deferrals to these customers). At peak levels, $266 billion, or over 10 per cent of all ADI lending was subject to repayment deferral, mostly loans to small and medium businesses and home loan customers.

APRA was able to provide this concessionary treatment for such a large portfolio of loans because of the fundamental strength of the banking system. In recent years, banking system capital adequacy has been built up to historically high levels, with a view to that resilience being available to be utilised in times of crisis. COVID-19 was such a time.

Nevertheless, to provide transparency as to the extent of the concession, APRA collected and subsequently published data on these temporary loan repayment deferrals. This data is significant because loan repayment deferrals – while an important source of flexibility and support to borrowers impacted by COVID-19 – also represent a key area of risk to Australia’s banking sector and economy. The risk is that at the end of their repayment deferral periods, many borrowers may still be unable to make loan repayments, which could lead to an increase in loan defaults, impacting both the borrower and the lender. An increase in defaults also places additional strain on ADIs’ capital levels, which may constrain their ability to continue to lend to viable borrowers.

Publishing the loan repayment deferral data enables market participants and the general public to develop a greater understanding of the scale and nature of this credit risk. This is important because markets depend on information, and the absence of information can lead participants to assume the worst. In times of uncertainty – as we are currently experiencing – timely, reliable and accurate information is especially valuable.

Collecting and publishing the data

The move towards collecting and publishing more data on ADIs was already underway before the pandemic struck.

In December 2019, APRA committed to substantially increasing transparency by making more data on ADIs publicly available. This move to greater transparency was aimed at increasing accountability, supporting competition and lifting overall standards in the banking industry. While COVID-19 resulted in some of APRA’s strategic priorities being adjusted, it didn’t change this commitment.

It was important for APRA and other regulatory and policy agencies (including the Treasury, RBA and ASIC) to understand the nature and scale of loans with deferred repayments. APRA worked with these agencies and the banking industry to collect data on a staggered basis, allowing smaller ADIs more time to adapt and report on these new categories of loans.

APRA first collected data on repayment deferrals from March, and expanded to all ADIs from June onwards. This data was necessary in order to clearly understand the banks’ level of support, the impact of COVID on borrowers, and the areas where there was a potential higher risk of default. The positive response by ADIs in implementing processes and upgrades to reporting systems in a short time was vital to APRA and other agencies’ understanding of the potential issues and making timely policy decisions, such as the extension of concessional capital relief to March 2021.

The first publication, released in July, contained data on total values, risk profiles and the number of deferred facilities. After this, entity-level data was released, containing data on an ADI-by-ADI level to investors, shareholders and customers. This entity-level publication was first released in September for data covering June and July reporting periods. APRA continues to publish this data on a monthly basis.

What does the data tell us?

The analysis of data on repayment deferrals has three components:

- The overall scale of support provided by the banks.

- Indicators which help assess risks within the deferred loan repayment portfolio.

- Changes to the level of support and outcomes at the end of the repayment deferral period.

Temporary loan repayment deferrals have been steadily decreasing since May, with the largest decline coming in October, which marked the end of the initial six-month period of deferral offered to many COVID-impacted customers. In October, only 3.3 per cent of all loans were subject to repayment deferral.

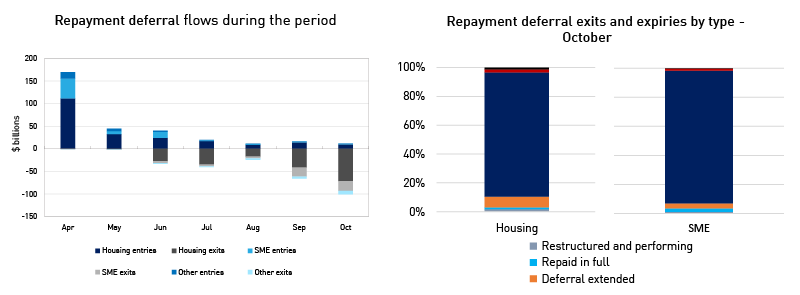

Loans that have expired or exited from temporary repayment deferral far outweigh new entries and extensions to deferral, and have done so since July. New entries into repayment deferral fell to their lowest level since their introduction, at $1.7 billion in October. To put this figure in context, it represents less than 0.1 per cent of all lending by ADIs. The vast majority of borrowers that have exited temporary deferrals have continued to make repayments and these loans have returned to a performing status. Very few of the deferrals which exited or expired in October required further extensions of their deferrals, in contrast to the trend in previous months where around 20 per cent of deferral exits were extended.

In terms of deferrals on housing loans, 89 per cent of exits from deferral returned to performance, while 8 per cent were extended for a further period. A small proportion of housing loans that exited from deferral in October (2 per cent) have not resumed repayments and have been categorised as non-performing. In terms of lending to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), 93 per cent of loans that exited temporary deferral in October returned to performance, with only 3 per cent of repayment deferrals being extended and 1 per cent classed as non-performing.

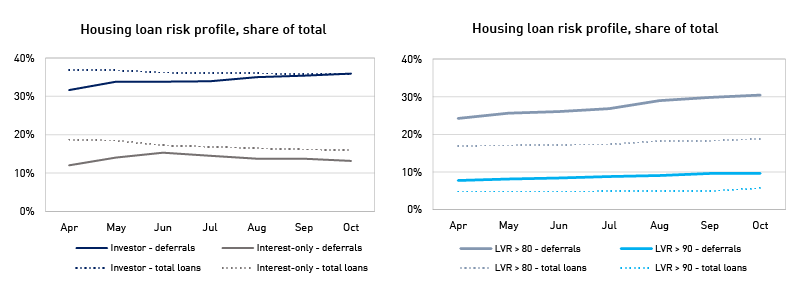

Unsurprisingly, the characteristics of loan repayment deferrals tend to be riskier than loans not in deferral. These risk characteristics have also changed since April, particularly for housing borrowers, indicating that loans that remain subject to repayment deferral are of a higher risk category than those which have exited repayment deferral and are already resuming repayments.

In particular, loans with higher loan-to-value ratios (LVRs) have formed an increasing share of housing loans with repayment deferrals. The LVR is a measure of the size of the outstanding loan, as compared to the value of the underlying property. Repayment deferrals with LVRs greater than 80 per cent reached 30 per cent of total housing loan deferrals in October. This is significantly higher than the representation of loans with LVRs greater than 80 per cent in total housing loans, which was 19 per cent in October. This shows that borrowers who have larger amounts owing on their loans, compared with the value of their properties, have been less likely to resume repaying their loans since entering into repayment deferral.

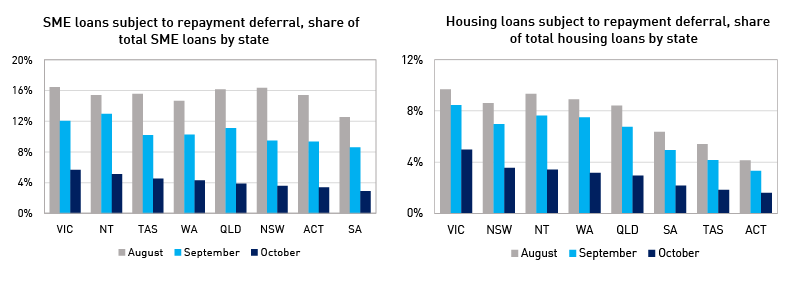

Victorian housing loans are more likely to be in repayment deferral than loans in any other state or territory, at 5 per cent in October compared with 3 per cent for the rest of the country. Victorian businesses are also most impacted, with 6 per cent of all SME loans in repayment deferral. This data is unsurprising given Victoria’s experience of the pandemic.

APRA and the ADIs continue to monitor a broad range of data and information, such as that shown above, which allows the industry to prioritise assisting borrowers and monitoring loans where there is greater risk. As long as this remains an area of heightened risk and focus, APRA will continue to monitor key data on temporary loan repayment deferrals and make that information public.

The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) is the prudential regulator of the financial services industry. It oversees banks, mutuals, general insurance and reinsurance companies, life insurance, private health insurers, friendly societies, and most members of the superannuation industry. APRA currently supervises institutions holding around $9.8 trillion in assets for Australian depositors, policyholders and superannuation fund members.