APRA Explains: Liquidity in banking

At its most basic level, liquidity is the ability to access cash when it is needed. Liquidity is an important consideration for all APRA-regulated entities: banks need to be able to pay depositors their money, superannuation funds need to be able to pay out benefits and requests for the release of funds, and insurers need to be able to pay claims – sometimes at short notice (such as the COVID-19 temporary early release of superannuation scheme, or the large number of insurance claims after the 2019/2020 summer bushfires).

In relation to banks, there are three different types of liquidity that are relevant:

- Funding liquidity: this relates to the ability of banks to pay their debts when they are due.

- Central bank liquidity: this relates to funding provided to market participants.

- Market liquidity: this relates to the ability of investors to trade assets in the market (for example, an asset is liquid if it can be easily sold in large amounts with only small changes in its price).

This article focuses on funding liquidity, which is critical to the safety and stability of banks, credit unions and building societies (collectively referred to as ‘banks’ in this article), and which is central to the work done by APRA and its peer regulators around the world.

Liquidity risk

Banks need to manage their funding liquidity risk carefully. This is because banks typically borrow a significant part of their funding from depositors for short terms (indeed, a substantial portion is available to be withdrawn at any time), while at the same time they often lend that money to customers for much longer terms, such as for a 30-year home loan.

If depositors want to withdraw their deposits after a short time, the bank cannot immediately get money back from the home loan. This means the bank either needs to:

- have a supply of cash on hand;

- borrow new money from another depositor/investor, or

- sell an asset to raise the funds.

Having sufficient ability to always do some or all of these things is crucial, because the community relies on banks being able to repay their creditors – such as depositors and bond-holders – as and when those debts are due. An inability to pay jeopardises depositors’ savings and disrupts customers’ ability to pay bills, transfer funds, or receive income. It would also severely undermine confidence in the safety of the broader financial system.

Prudential regulators such as APRA devote considerable resources to ensuring that banks are managing liquidity risk very carefully.

APRA and liquidity risk

APRA’s mandate is to protect the community by ensuring that, under all reasonable circumstances, financial promises made by the institutions it supervises are met within a stable, efficient and competitive financial system. So a central part of APRA’s work is to ensure that banks limit the extent of their liquidity risk. APRA seeks to do this in a number of ways, including:

- APRA requires banks to hold a minimum level of liquid assets (assets that can be easily and quickly converted to cash) against possible liquidity risk. The key regulatory ratios banks must meet is known as either the ‘Liquidity Coverage Ratio’ or the ‘Minimum Liquidity Holding Ratio’.

- APRA requires larger, more complex banks to structure their borrowing and lending so that there is less opportunity for liquidity risk to arise. This is achieved through a regulatory requirement known as the ‘Net Stable Funding Ratio’.

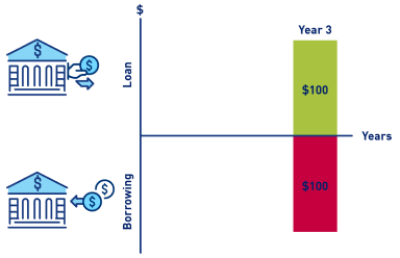

The diagrams below illustrate liquidity risk.

In Diagram 1, a bank loans $100 to a corporate customer for three years, and funds it by borrowing $100 from another customer – a corporate depositor – for three years.

When the corporate customer repays the loan in Year Three, the bank receives $100, and uses that money to repay the corporate depositor. The bank has fully matched its liability, so it runs no liquidity risk.

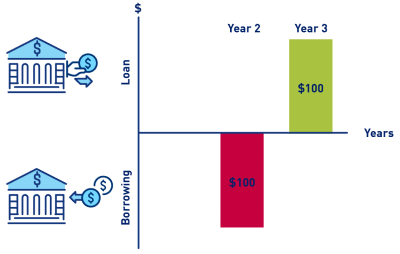

Alternatively, a bank may take a shorter term deposit to fund its three year loan.

In Diagram 2, the bank loans $100 to a corporate customer for three years, and funds it by borrowing $100 from another customer for two years. In this case the bank runs liquidity risk, as it will need to repay its borrowing when it matures in Year Two. The bank will therefore need to be confident it will have other sources of funding available to it to repay the $100 deposit before the loan is repaid.

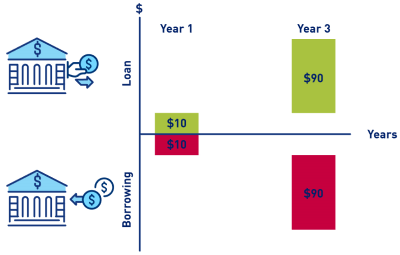

Banks typically adopt a more sophisticated approach that takes customer behaviour into account. For example, while typical savings accounts may be withdrawn immediately, depositors do not usually withdraw all of their money at the same time. This mitigates funding liquidity risk. If typically only 10% of such deposits is at risk of being withdrawn in Year One, and the remainder stays with the bank for three years, a different picture emerges.

In Diagram 3, the bank loans $100 to a corporate customer for three years, and funds it by borrowing from a group of retail depositors, with withdrawals of $10 and $90 expected in Years One and Three respectively.

In this case the bank still runs liquidity risk, but at a much smaller level. The bank only needs to be confident it will have other sources of funding available to it to repay the $10 deposit before the loan is repaid.

Diagram 4 outlines how a bank may reduce liquidity risk by holding liquid assets.

In this case, the bank makes a $90 corporate loan for three years, buys $10 in a highly liquid asset like Australian Government Securities (AGS), and funds both by borrowing $100 from a group of retail depositors, with withdrawals of $10 and $90 expected in Years One and Three respectively.

In this case the bank has eliminated its liquidity risk, as it may sell the AGS to repay Year One deposit withdrawals, and use the proceeds of loan repayments to repay Year Three withdrawals. Of course, this is subject to the assumed timing of the deposit withdrawals being as expected – it may vary according to circumstances, so in practice banks would typically hold additional liquid assets to allow for a degree of variability in deposit outflows.

Australian liquidity regulation

APRA’s ADI Prudential Standard 210 (APS 210) is mostly focused on funding liquidity. It aims to ensure that ADIs have sufficient High Quality Liquid Assets (HQLA) on hand to repay any funding withdrawals in the short-term, that their balance sheets are appropriately structured to minimise funding liquidity risk in the longer term, and that boards and management have a strong framework in place to manage liquidity.

For larger, more complex ADIs, APS 210 requires that they manage a Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) that reduces liquidity risk over the month ahead during an assumed period of stress, and a Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR) that minimises liquidity risk over the next year. For less complex ADIs, APS 210 requires that they maintain sufficient minimum liquid holdings (MLH) to manage liquidity risk over both short and longer periods.

Funding liquidity risk is inherent in banking and APRA’s regulation of funding liquidity is an important tool in reducing that risk. The liquidity ratios determined by APRA are central to ensuring that all Australian banks effectively measure and manage their liquidity risk, making the banking sector more robust and thereby protecting the interests of Australian depositors, and the stability of the broader financial system.

The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) is the prudential regulator of the financial services industry. It oversees banks, mutuals, general insurance and reinsurance companies, life insurance, private health insurers, friendly societies, and most members of the superannuation industry. APRA currently supervises institutions holding around $9 trillion in assets for Australian depositors, policyholders and superannuation fund members.