Myths and misconceptions should be no barrier to super consolidation

COVID-19 has presented challenges for all APRA-regulated industries – indeed, it’s disrupted almost all sectors of the economy – and superannuation is no exception. Australia’s retirement income system is among the best in the world, but a combination of falling asset prices, liquidity pressures and declining member contributions have put many funds’ financial and operational resilience to the test over recent months.

The short term impact of the COVID-19 crisis will pass, but some of its effects will be long-lasting. Declining returns, reduced portfolios and membership bases, and pressure on costs will challenge many funds’ ability to continue to provide value to members. This will generate a need, amongst other things, for some funds to more actively consider merger options than they may have done to date. The impacts flowing from COVID-19 will be significant for some funds, accelerating sustainability challenges that otherwise would have emerged over a slightly longer timeframe.

What APRA has observed over the past few months is that not all funds are equally well equipped to handle shifts in the landscape. Those that are well-resourced and well-governed, and with robust investment management and operational processes, are most likely to be better positioned to weather the short and long term impacts of COVID-19. It has been a timely reminder that trustees must continually reassess and be able to demonstrate their “right to remain”, and that for some the only way forward to secure the future of their members for the long-term may be to exit the industry and pass on the trusteeship of their funds to others who are better equipped for the task.

APRA’s efforts to encourage industry consolidation are often met with a long list of the difficulties of merging. Some of these are valid, but others are myths. While the decision to pursue a merger or transfer of trusteeship requires serious consideration and research, and there can be some operational issues to work through, many trustees appear to over-estimate the degree of difficulty and expense involved in the process, and under-estimate the benefits. Moreover, there are important steps all trustees can take now to put them in the best possible position to pursue or accept a merger offer should the need or opportunity arise.

Contraction in action

Before debunking some of the myths, it’s worth addressing another misconception about super industry consolidation: that it rarely happens.

In reality, consolidation and rationalisation of the industry has been steadily taking place over many years, and has continued since the introduction of APRA’s prudential framework in 2013. Over the past seven years, the asset pool being managed by APRA-regulated funds has more than doubled, from $0.96 trillion in June 2013 to $2.0 trillion in December 2019, whilst the number of APRA-regulated funds has decreased by one-third, from 279 to 185 over the same period.1

In APRA’s view, even 185 funds (which offer more than 40,000 investment options) is still a large number and means the industry is probably not operating with maximum efficiency. APRA continues to pressure the trustees of poor performing funds to merge or exit the industry unless they are able to materially lift their game. This pressure is being applied through the introduction of a stronger prudential framework (including the implementation of SPS 515 Strategic Planning and Member Outcomes), intensifying our supervision activities and the publication of a MySuper Heatmap exposing poorer performers.

Narrow thinking

A common reason trustees offer APRA for not progressing mergers or fund transfers is difficulties in complying with the equivalency test contained in the successor fund transfer provisions of the Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Act 1993.2 These provisions require the trustees of both the receiving and transferring fund to agree that the transfer will confer “equivalent rights” to transferring members, and that both trustees involved in the process form the view that the transfer is in the best interests of members.

Mergers are often stalled or abandoned by trustees that appear to take an overly narrow or restrictive interpretation of the legislation governing mergers. APRA expects trustees to take a pragmatic approach to this assessment – a holistic and “on balance” assessment of equivalency, rather than a line-by-line “same rights” approach. Where equivalence remains an issue, the trustees involved should actively consider negotiating trust deed amendments in relation to member rights, rather than abandoning the possibility of a merger.

To reiterate3:

- Members’ rights are those they are legally entitled to under the fund’s governing rules, such as access to insurance.

- Rights are not features. Features are determined by trustees, can be changed and provide no ongoing entitlement to a member, such as call centre access or online access to interactive tools. Generally, features may include the quantum and nature of fees that will be charged to a member; the level of insurance cover and its cost; other product features such as particular investment options; or the availability of services such as a phone app.

- The assessment of equivalency of rights means that the members’ rights in the receiving RSE are required to be equivalent, but not equal.

- Whilst the equivalent rights apply to members, APRA expects that trustees consider the rights provided to cohorts of (rather than individual) members, such as default members.

- Transfers of members between MySuper products will, in almost all instances, satisfy the equivalency test as, under law, MySuper products are required to have the same core characteristics and embedded rights.4

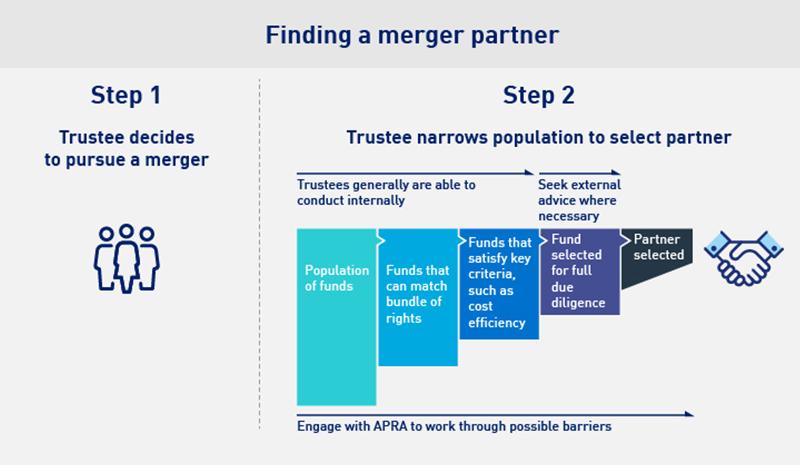

The legislative framework enables trustees to undertake a merger without any direct involvement from APRA, and mergers can generally be undertaken in-house with external experts engaged as appropriate. However, APRA encourages trustees to engage with their supervisor in relation to their approach to a potential merger, including the assessment of equivalent rights, at an early stage.

Costs vs benefits

Resistance to consolidation isn’t isolated to the crimson sections of APRA’s MySuper Heatmap: even stronger performing funds can be quick to present arguments why a potentially advantageous acquisition gets consigned to the “too hard basket”.

These trustees, that are otherwise open to acquiring funds, express legitimate concerns about the due diligence costs and effort involved. They worry about what liabilities they are taking on: unit pricing errors, insurance disputes, inadequate reserves that would otherwise provide some recourse to be indemnified for these unknowns. These issues impact their appetite for taking on a merger given they need to assess whether it is in the best interests of their existing membership. To overcome this, trustees that may be seeking a merger should take steps to address these issues to improve their prospects of finding a suitable partner. For example, ensuring reserves are sufficient to cover expected liabilities is something that funds should be acting on now.

When developing a business case for a merger, trustees undoubtedly need to consider the costs associated with the merger and the impact those costs will have on their members. However, these costs need to be considered over the medium to long-term, and need to be balanced against the benefits to be gained from the merger over the same period. This recognises the relatively long horizon over which a trustee manages members’ retirement savings.

Potential capital gains tax liability has been cited as a barrier to mergers in the past. The recent passage of legislation5 that makes capital gains tax relief permanent for merging funds provides certainty and removes this hurdle.

Sealing the deal

Narrowing the population of potential partners is the first step in any merger process, and should be driven by an assessment of the successor fund’s ability to provide members with equivalent rights as part of the transfer. Once a short-list of potential successor funds that are able to match the bundle of rights and satisfy key criteria is identified, trustees must select their preferred partner, mindful of their duty to act in the best interests of members.

In practice, this can be satisfied by a due diligence process that balances consideration of inter alia, costs, systems compatibility, product design including insurance offering, ‘governance, people and culture’, and performance across investments, fees and costs and longer term sustainability. For example a trustee may choose one partner over another because they share a common administrator which would lead to cost efficiencies, existing similarities between investment strategies that would simplify migration, similar insurance design, in-house capability or a desire to leverage off the in-house capability of the successor. Both trustees looking to merge would consider these matters, albeit with a different emphasis depending on their motive to merge. Whilst there are costs associated with undertaking due diligence, a well-considered process that identifies opportunities for cost-savings as part of the merger, benefits members.

The trustee’s ability to work through these considerations largely depends on the reliability of its data. Data plays a key role in the successful running of any business and superannuation is no different. Trustees that operate their funds on unified administration platforms from which reliable data can be analysed are well-placed to satisfy APRA’s regulatory expectations going forward, and for those contemplating a merger, it makes them a more attractive proposition.

Conclusion

The trustees of funds that face sustainability challenges should, as part of their board strategy, develop an ‘exit plan’. This would ideally put performance triggers in place that enable the trustee to make the call to exit, and involve periodically scanning the landscape for partners so that they are prepared to negotiate a merger on their own terms, rather than be compelled to undertake it because they have no other options.

Ultimately, the decision to merge or wind-up a fund is primarily one for trustee boards to make, however APRA is ensuring that trustees keep all options for improving member outcomes on the table, including merger or wind-up options. APRA acknowledges that it can be difficult to reach the decision to exit, and there may be challenges associated with finding a suitable merger partner. That doesn’t mean that these important decisions should be avoided or deferred, or that (sometimes questionable) reasons are found to avoid a merger that otherwise appears to be in members’ best interests.

APRA takes a facilitative approach to mergers and urges trustees to approach APRA early to discuss their merger plans – to work together to address any perceived barriers. Given the diversity of fund structures and product offerings across the APRA regulated population of funds, APRA’s view is that there is a merger partner for all funds – it’s just a matter of finding the right one.

Footnotes

1 Funds with less than five members are excluded from these statistics.

2 Refer to r. 6.29 and r 1.03 of the Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Regulations 1994 (SIS Regulations).

3 For more detailed guidance on the process for undertaking a successor fund transfer, refer to Prudential Practice Guide SPG 227 – Successor Fund Transfers and Wind-ups.

4 Part 2C Superannuation (Industry) Supervision Act 1993

5 Treasury Laws Amendment (2020 Measures No.1) Bill 2020

Media enquiries

Contact APRA Media Unit, on +61 2 9210 3636

All other enquiries

For more information contact APRA on 1300 558 849.

The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) is the prudential regulator of the financial services industry. It oversees banks, mutuals, general insurance and reinsurance companies, life insurance, private health insurers, friendly societies, and most members of the superannuation industry. APRA currently supervises institutions holding around $9 trillion in assets for Australian depositors, policyholders and superannuation fund members.