Soft Stuff

Ian Laughlin, Deputy Chairman - 31st Governance Institute of Australia National Conference, Brisbane

You won’t find this in the legislation, but on one view the prudential regulatory world is made up of hard stuff and soft stuff.

What does that mean?

Well, hard stuff includes things like quantitative requirements for capital, ratios, margins, and the like. It also includes many of the specific requirements in APRA’s prudential standards where it is usually clear how the requirement can be met.

Soft stuff includes things that are not so easy to measure, such as qualitative assessments, culture, values and behaviours.

Most people – institutions and regulators - are naturally more comfortable with the hard stuff. Hard stuff is easier to understand, and easier to assess. Soft stuff is more amorphous – it is difficult to assess and at times not at all easy to understand.

In other words, and rather paradoxically, hard stuff is actually not so hard, and soft stuff is hard.

Much of what APRA does falls into the hard stuff bucket. But we are giving increasing attention to the soft stuff. This all presents challenges – for us as regulator and for the institutions we supervise.

So why are we doing this? Well, let’s consider the matter of risk culture.

Since the GFC, the international regulatory community has spent much time and effort on rules and regulations (Basel III in the banking world is a good example). But it is also increasingly recognizing the fundamental importance of risk culture and is turning its mind to this – for example from the Financial Stability Board.[1]

It is generally accepted that inappropriate culture was at the root of many of the problems that emerged in the GFC (such as the packaging of poor quality mortgages into AAA securities and the way they were sold). And in the problems that came to the surface since then (such as the LIBOR scandal and the attitudes that allowed it to evolve). And indeed in many of the problems that emerged before the GFC (such as Nick Leeson’s escapades, and the failure of HIH).

The recent clippings[2] on the slide show that culture is a real ongoing concern.

But there is another reason why risk culture is becoming more important to us. At APRA, we already place great importance on supervision. However, in a world of deregulation and aversion to ever more regulation, supervision will assume an even more important role. Supervision will fill needs that might otherwise have been met by regulation. And an understanding of risk culture and its importance to prudent management is core to good supervision.

More on risk culture and other soft stuff shortly.

First, to help you better understand our interest in this, let me spend a few minutes on APRA and our approach to our job.

The APRA Act sets out APRA’s purpose, and various industry-specific acts provide us with supervisory powers. Our Mission provides a good overview of these more formal arrangements.

The first point to note is the attention given to financial promises being met by institutions. So this drives much of what we do.

The second leg to our Mission reflects a requirement in the APRA Act that “APRA is to balance the objectives of financial safety and efficiency, competition, contestability and competitive neutrality and, in balancing these objectives, is to promote financial system stability in Australia.” This means that safety is not everything, and an appropriate balance is necessary. This needs judgement, with soft stuff again assuming some importance.

Now, promises made by an institution are much more likely to be kept if it is prudentially sound.

And a prudentially sound institution must have very solid foundations.

Those foundations have three key elements:

- Capital management

- Risk management

- Governance

All three of these elements must be strong. If any one of them is weak, then the foundations will be unstable, prudential soundness will be in doubt, and the promises at risk.

Not surprisingly, therefore, we pay attention to each of the three elements of the foundations.

We address the three elements in a number of ways – in particular, through prudential standards[3] and supporting guidance, supervision, and assurances from various experts, the board and management.

We back up our prudential standards with very active supervision. Indeed, supervision is at the heart of APRA’s role as a prudential regulator.

All of this is supplemented by formal assurances and assessments (e.g. by auditors, actuaries, the CEO or the board).

Capital and liquidity management is nearly all hard stuff – there are various quantitative measures, specific requirements etc.

Governance and risk management have both hard stuff and soft stuff. Let me explain.

APRA has done a great deal of work on risk management hard stuff in recent years, with ongoing development of prudential standards and active engagement with institutions.

By and large, institutions have responded well, and we have seen marked improvements in the overall standards of risk management.

A new multi-industry prudential standard, CPS 220, comes into force on 1 January. This draws together the developments in our thinking over recent years and includes a number of hard requirements, including that an institution must have;

- a risk management framework;

- a risk appetite set by the board;

- a board-approved risk management strategy (which amongst other things sets out the approach for instilling an appropriate risk culture);

- a Chief Risk Officer; and

- a Board-approved business plan.

Now while these are hard requirements, they have elements of soft stuff. For example is risk appetite hard stuff or soft stuff? It’s a little bit of both. We certainly want to see hard measures of risk wherever possible. But we also expect the risk appetite statement to convey a message which goes beyond the numbers. And here we get into soft stuff.

Let’s go back now to risk culture.

There are many definitions[4] of risk culture – most quite complex. However, I don’t think we need to be too concerned with its precise definition.

A reasonably simple way to look at it is as follows: those aspects of the organisation’s culture that influence its management of risk.

Of course, culture is often described as "the way we do things around here". So a good working definition of risk culture is "the way we do risk around here".

Culture is about what is truly important in an organization. It is about the way people actually behave (rather than what they should do, or even would like to do).

What about values and behaviours? How do they relate to culture and what comes first? What is a function of what?

There are plenty of learned views on all of this, but for our purposes we don’t need to be too complex.

We might start with the premise that what is ultimately important for the prudent management of an institution is what decisions are made and what is actually done. In other words it is behaviour that is fundamentally important to prudential outcomes.

But culture is “the way we do things around here”. So we might then conclude that behaviour is an outworking of culture.

But then culture surely should be driven by the organisation’s values.

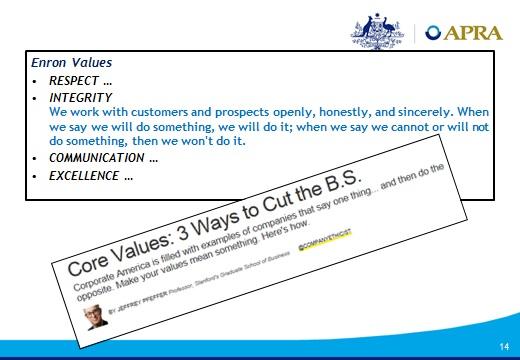

So a set of values that the board considers fundamentally important is a good starting point. But it is nowhere near enough, because so often those well-meaning values go no further than the poster on which they are printed.

So in our approach to supervision, we go a step beyond values and look to the board to actively seek the right sort of culture – in particular risk culture.

So what is needed for a sound risk culture? Here are a few thoughts:

The risk appetite must be clear and unambiguous; the espoused values must be clear, and consistent with the risk appetite and the business strategy; those values must be embraced across the organisation; and decision-making must be consistent with the values, risk appetite and business strategy.

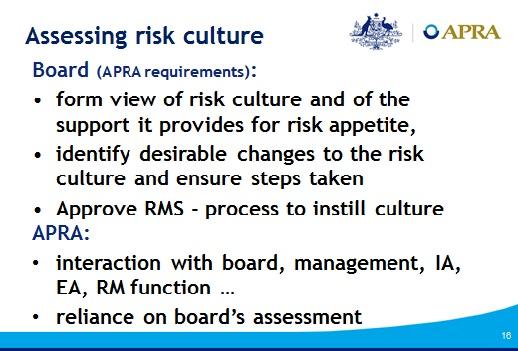

Under the new prudential standard, CPS 220, the board must ensure that “it forms a view of the risk culture in the institution, and the extent to which that culture supports the ability of the institution to operate consistently within its risk appetite, identifies any desirable changes to the risk culture and ensures the institution takes steps to address those changes.”

So how does the board form such a view? Well that is exercising quite a few minds at present.

We are seeing a range of practices emerging.

First, directors will as a matter of course develop a view of risk culture from their dealings with management. But they can and should go further than this, and do so systematically. They might start by posing a series of challenging questions for themselves[5] and then seeking answers to those questions.

They also are able to draw on the experiences of internal audit, external audit and other advisers who all will have formed views, consciously or otherwise. We are aware of one internal audit function having professionally skilled staff on the team to help with risk culture. We were advised recently that one of the criteria in an external audit tender was how the auditor would help with the assessment of risk culture. Often, staff engagement surveys are being used to get some insight. Some boards are going further and engaging specialist advisers (and there are quite a few in the market, offering various techniques) to help with their assessment. There also are academics offering their services to boards.

APRA too forms views on risk culture from its various interactions across the business. To help with this, we have occasional less formal meetings with chairs of the board and the audit and risk committees, in addition to annual meetings with the full board.

Importantly, however, APRA will rely heavily on the board’s view of risk culture, and not just our own opinion.

Let’s now consider governance.

This audience does not need an explanation of governance, or its importance, but it is worth noting a subset to which we give particular attention – risk governance6.

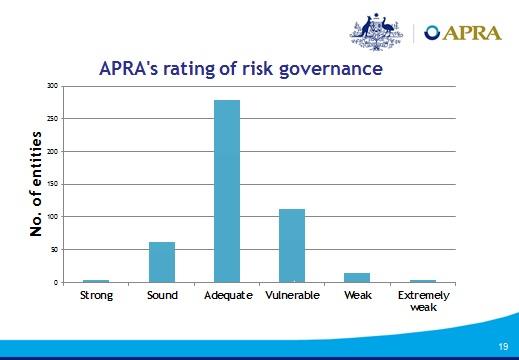

APRA makes formal assessments of the risk governance in each institution. We do this based on the many various interactions we have with an institution, quality of company policies, minutes of meetings etc.

You can see from the slide that we do not find consistently satisfactory standards, and so this is an ongoing area of focus for us. The reasons for the deficiencies are surprisingly basic in some cases – for example there might be a lack of direction from the board, or the risk appetite may be unclear. In some cases the KPIs are not aligned with the risk management framework. And so on.

It is worth noting that APRA has a number of specific governance requirements. These cover board size, board renewal, the need for various committees and fitness and propriety matters.

There are quite a few specific responsibilities imposed on the board in our prudential standards (e.g. that the board must ensure an adequate level of capital, or set the risk appetite). This sometimes generates concerns that APRA expects too much of boards. Or that we expect boards to take responsibility for what is normally seen as the province of management.

Let me finish by commenting briefly on that point.

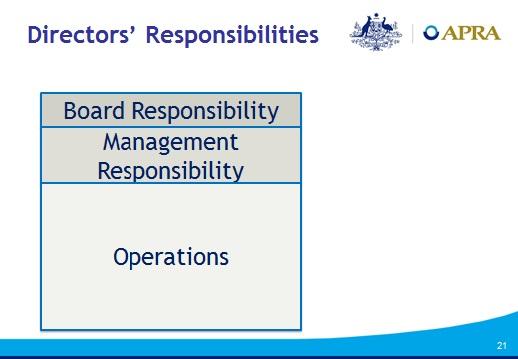

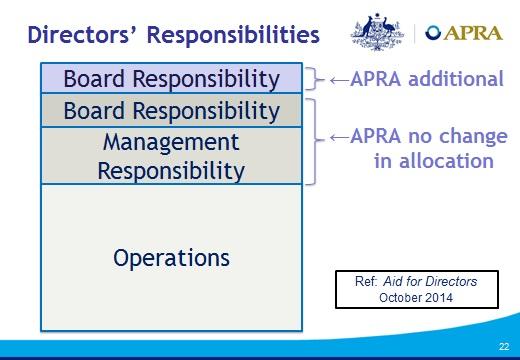

This slide is a simple representation of the conventional division of responsibilities – in particular between board and management.

The boundaries are generally clear and delegations and responsibilities well accepted in the business world.

Let me be clear: APRA is not seeking to change the boundary of responsibilities between management and board from generally accepted practice. In particular, it does not expect the board to be involved in operational matters.

However, for an APRA-regulated institution, there are additional board responsibilities for the board as explained earlier.[7] That is unambiguously the case. However, there is no intent that any of those additional responsibilities would in the normal course of events lie with management.

In conclusion, I hope this overview has given you some insights into why we consider risk culture and risk governance to be so important, and how we are tackling them in our regulation and supervision.

Footnotes

- For example, see this FSB paper http://www.fsb.org/2014/04/140407/.

- For example, see https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2014/11/20/lying-cheating-bankers.

- Prudential standards are our primary vehicle for setting out requirements for institutions and have the force of law. Prudential standards are very much about good practice. A well-governed, well-managed, well-capitalised institution should be doing most of what is in the prudential standards as a matter of course.

- See, for example, Risk Culture and Effective Risk Governance (edited by Patricia Jackson), chapter 2.

- For example:

- How does the board satisfy itself that the espoused values are truly supported by management and staff at all levels?

- Do remuneration and KPIs consistently support and drive the desired risk culture?

- How does the board gain a clear understanding of the quality and consistency of decision-making throughout the business and it is satisfied that this driving an appropriate risk culture?

- Risk governance applies the principles of good governance to the identification, assessment, management and communication of risks. Source: International Risk Governance Council.

- For more information, see Improving APRA's board engagement.

The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) is the prudential regulator of the financial services industry. It oversees banks, mutuals, general insurance and reinsurance companies, life insurance, private health insurers, friendly societies, and most members of the superannuation industry. APRA currently supervises institutions holding around $9 trillion in assets for Australian depositors, policyholders and superannuation fund members.