Preparing for the unexpected - Insights from APRA’s 2015 Life Insurance stress test

Geoff Summerhayes, Executive Member - Speech delivered to insurers who participated in APRA’s 2015 Life Insurance Stress test, APRA Offices, Sydney

Good morning, it’s good to be with you.

As participants of APRA’s most significant industry stress testing exercise for the life insurance sector let me start by saying that this was deliberately set to ‘raise the bar’. And not just for you who were involved, but the entire industry.

I say this because the industry has in the past not necessarily viewed stress testing as part of its ‘DNA’. While insurance companies have been adopting sensible practices over the years, including regular sensitivity testing and internal stress scenarios, the reality is that more rigorous stress testing exercises, conducted at a whole of business level, are still evolving. What was once viewed as a backroom activity performed by the actuarial team is now expected to reach further into the organisation if it is to be effective in making organisations resilient to adverse shocks. These events can come in many forms and will not present themselves in an orderly fashion, as was the case in our stress test. Insurers must be ready to respond to real-life shocks and to do that they must become adept at asking the question: “what if?” In doing so, insurers should not just think about adverse events arising from elsewhere; they should also ask the more uncomfortable question: “what if we are at the heart of the problem?”

And what better time to do so. At this moment the life insurance industry is under considerable pressure, facing significant issues, many of which, with the benefit of hindsight, have been quietly festering. Some of these relate to the recent concerns with claims management practices, raising questions about culture and conduct. The mispricing of risk, in group insurance schemes and disability products has seen profitability in recent years fall and these issues are not yet resolved. Legacy products continue to amplify complexity and operational risk, creating opportunities for innovation and disruption which places pressure on incumbent insurers.

Clearly, insurers are being tested, and there is a lot at stake. Life insurance plays an important role in the Australian economy. The products offered and the great good these benefits do for those in our community, who are often experiencing significant personal distress when calling on their policies, cannot be underestimated. It is with pride that the industry should hold its licence to offer this ‘social good’. But trust in the sector has waned despite the strengthened capital levels since the global financial crisis. This diminished sentiment needs to be reversed; ultimately, regulatory capital won’t help institutions if they can’t be trusted.

While I do not wish to delve further into this issue today, I mention it as an important lens from which to view stress testing. Benefit of hindsight aside, it is plausible that, had insurers been in the habit of applying robust and regular scenarios designed to test their ability to respond to some of the present challenges, they could have been better equipped to manage them and the associated reputational damage.

Today I intend to focus on the key insights of the APRA stress test and expectations going forward for all insurers, in what is a very challenging time for the industry.

Setting the scene

Before I do this, I need to set the scene more broadly about the role of stress testing.

A key plank of APRA’s mandate is to promote financial stability. APRA’s strategic plan sets out its three primary functions: supervision, policy and resolution. All of these play a part in financial system stability, and stress testing fits squarely within this mandate, complementing the more prescriptive capital rules that apply to financial sector entities and APRA’s risk-based supervision approach. Stress testing acts as a further protector of financial health alongside our prudential requirements and supervision activities, improving the readiness of the sector to withstand adversity, by enhancing capital management, informing recovery planning and reducing the likelihood for failure and resolution. Designing and playing out a scenario under a theoretical but entirely possible adverse situation is part of the regulators’ armoury and has gained greater focus since the global financial crisis, with regulatory agencies and financial institutions becoming more sophisticated in their approach to both industry-wide and entity-level stress testing.

As you know, APRA has performed a number of stress tests across the banking industry. More recently, in 2014 we undertook an exercise involving Australia’s largest banks to test capital resilience and improve capability. In 2015, a selection of banks were required to use a common scenario provided by APRA as part of their internal capital adequacy assessment processes, or ICAAPs. So, it is expected that at least most of our larger authorised deposit-taking institutions (ADIs) are further along the curve in terms of good practice on stress testing, given the focus and activity around this in recent times.

For life insurers (and general insurers, for which we have just released a similar stress testing exercise) we started with a set of objectives designed to uplift stress testing governance and capability, provide insights into capital resilience under a severe but plausible scenario and identify any new or emerging risks. We understood that this was the first comprehensive industry stress test of its kind for the industry and we also knew that the experience would likely be different than that seen for ADIs.

This is in part because of the heterogeneous nature of the life insurance industry compared to banking. Unlike their ADI counterparts, life insurance companies have very diverse business models and exposures. The participants involved in this stress test were a representative sample of the industry and included a mix of diversified insurers, reinsurers and risk specialists (some 54% of the market as measured by net premium revenue or 73% as measured by gross policy liabilities as at 31 December 2015). The diversity of the participants meant that each insurer was impacted differently by the stress scenario and hence responded differently. This posed challenges in interpreting the results, particularly at the aggregate level, and makes it difficult to make direct comparisons between insurers or to draw wider conclusions. I will however make some comments on the aggregate capital impacts and reinforce the importance of management actions and recovery planning in this context.

As mentioned, we were also cognisant that stress testing capabilities for life insurers were, in the main, not well advanced. While some insurers had been developing their stress testing frameworks, models and governance practices in recent times, most were still relatively immature. As we expect to undertake another industry stress test in future, likely to be 2018, we anticipate insurers will be better placed to undertake this exercise and our observation is that the 2015 stress test has lifted the focus and upped the standards already for those involved.

It is important to state too that APRA’s approach to stress testing is somewhat dissimilar to that which has evolved internationally. In the global banking arena, revelation of individual entity results in the interests of transparency, and capital implications, has been more the flavour. For APRA, we do not publish individual results, nor do we believe capital requirements should be set from those results. Rather, we think stress testing should inform capital decisions, helping to set target surplus thresholds and fostering greater understanding of the dynamic between capital and risk. This includes risks relating to conduct and reputation, as I highlighted earlier. Hence, today I will not reveal insurer-specific results, but will show an aggregate view and comment mostly on insights resulting from the stress test, and where improvements could be made.

The scenario

Let’s come back to the scenario itself. For the life insurers we used the same scenario we developed for the banking sector last year, based on a downturn in the Chinese economy leading to a decline in global growth and a recession in the Australian economy. At the macro level, GDP falls by 5 per cent and unemployment increases to 14 per cent. For insurers, the impact on employment and slower wage growth drives an increase in disability income insurance claims, with higher incidence rates in this class of business and for Total and Permanent Disablement (TPD) and longer periods on claim.

The stress also impacts asset classes, with severe downturns in property and equity prices and government bond yields, and an increase in credit spreads. As such, the stress was two-pronged, targeting both sides of the balance sheet.

Setting a severe but plausible scenario is always a challenge and one which we can never be sure to perfect. But based on the results, feedback from participants and a comparison with our regulatory capital requirements we feel the scenario achieved the targeted severity, balanced with plausibility. A word of caution here though before I go on. As an industry with significant actuarial presence, the question has arisen as to whether a probability of sufficiency, or degree of confidence, can be attached to the APRA scenario. The answer is no. This is because for a complex economic scenario with many moving parts, it is virtually impossible to do this at all accurately or meaningfully. Linking severity to probability in a mechanical way is not the core objective of an enterprise-wide stress test.

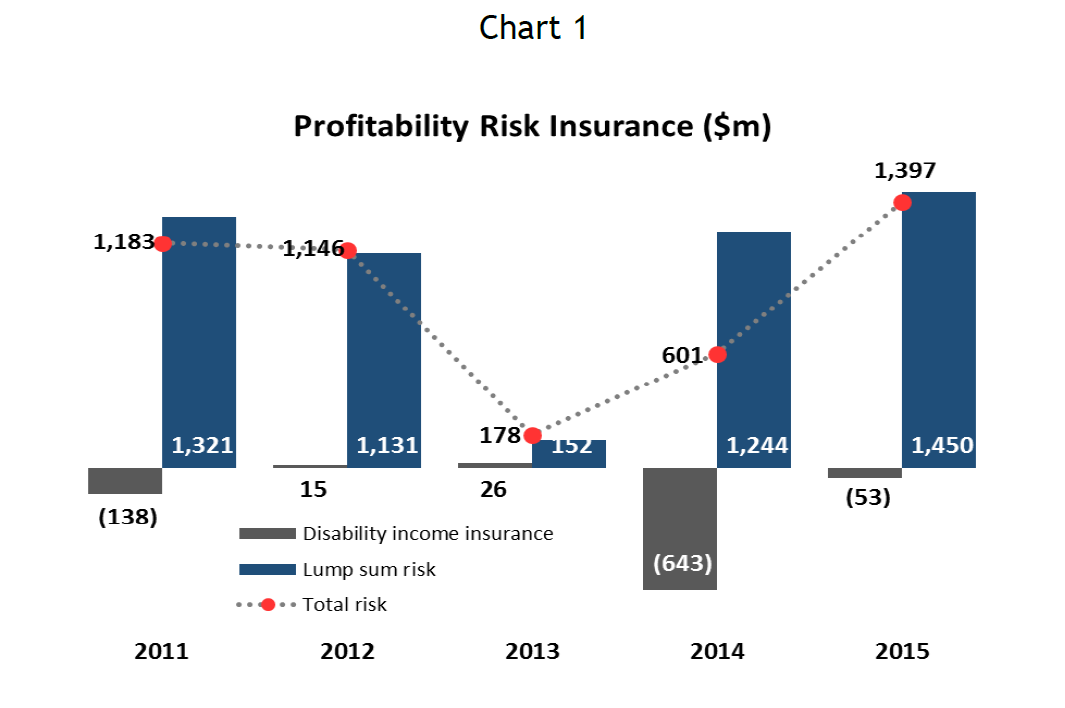

The scenario was targeted mainly at disability income insurance, a product that has in recent years become problematic for the life insurance industry. Chart 1 shows the profitability trends for this class of business compared with that for traditional lump sum risk business (i.e. death, trauma and TPD).

Results

I said earlier that the stress test was partly designed to identify any new or emerging risks. While institutions themselves gained further insights into their risk profiles, the results of the stress test did not reveal anything on the risk frontier that the industry and APRA were not already aware of. The stress test did though, put a spotlight on areas of concern, not the least being the exposure to disability insurance risks and the need to address problems with this product in the near term. I will say more about this later.

The results of the stress test showed that the scenario – not unexpectedly - had a severe impact on most insurers before the impact of management actions were allowed to be considered. For background, APRA prescribed certain actions that could be regarded as ‘before-mitigants’ (e.g. reduction in bonus and crediting rates for participating business) as distinct from those that could only be considered as post management actions or ‘after-mitigants’ (e.g. premium rate increases).

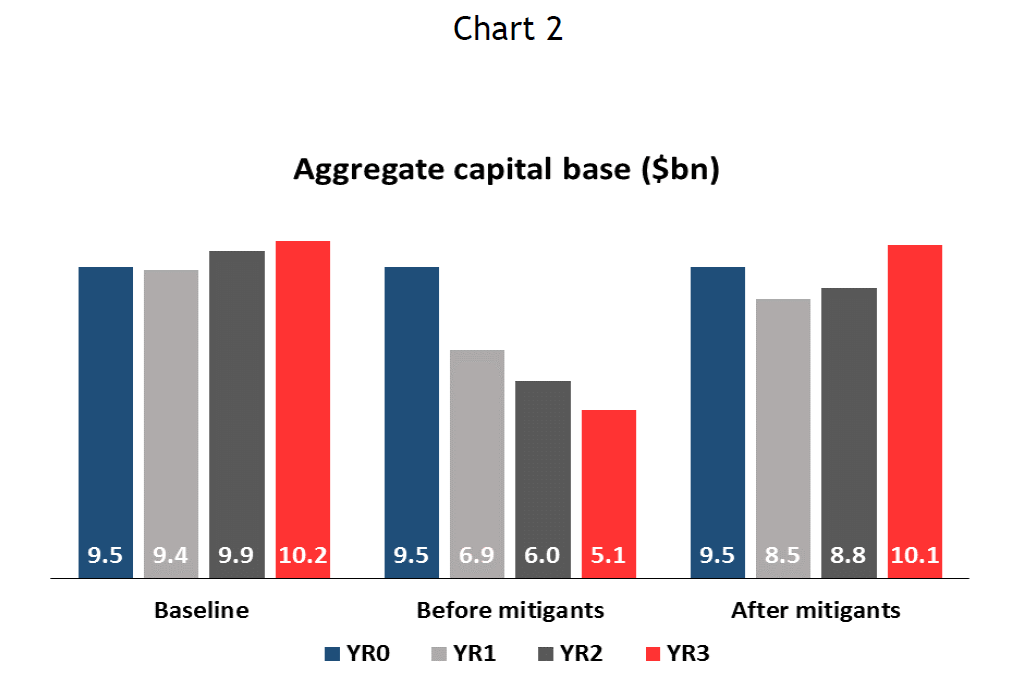

Chart 2 below depicts the impact on the aggregate capital base of the insurers involved in the test against their starting (baseline) position. The chart shows a capital impact of some $4.4 billion (46 per cent) from the baseline position (Year 0) to the end of Year 3 on a before-mitigants basis. After taking management actions however, aggregate capital returned to near pre-stress positions.

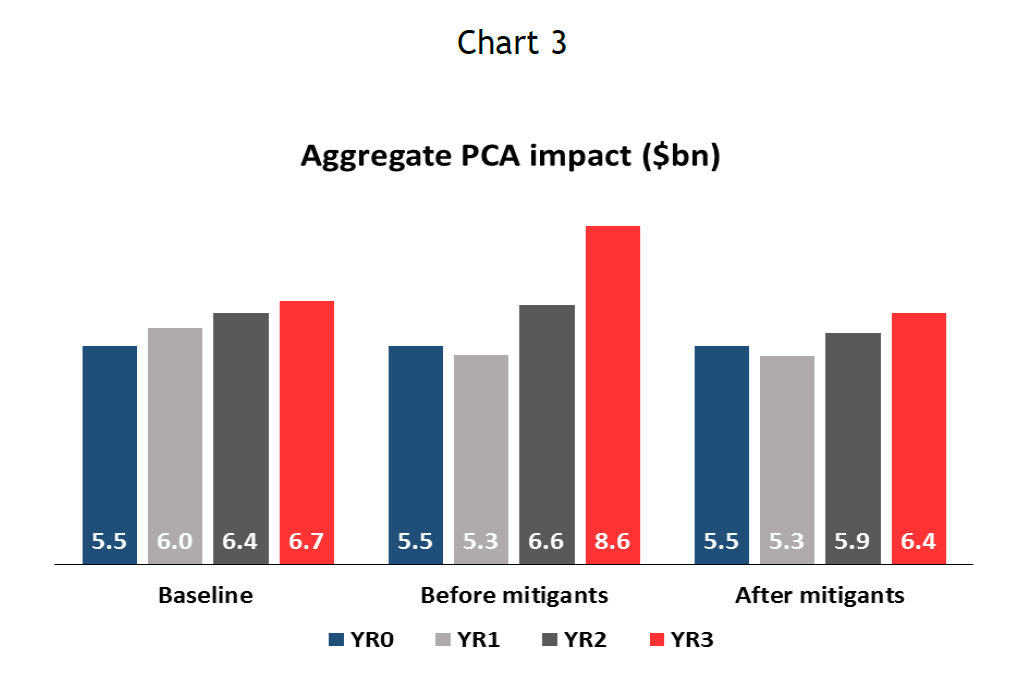

Chart 3 shows the impact on the regulatory capital required to be held under the scenario (i.e. the Prescribed Capital Amount or PCA) which increased by $3.1 billion (55 per cent) over the three years before the application of management actions. Once again, after mitigating actions the PCA returned to near pre-stress levels.

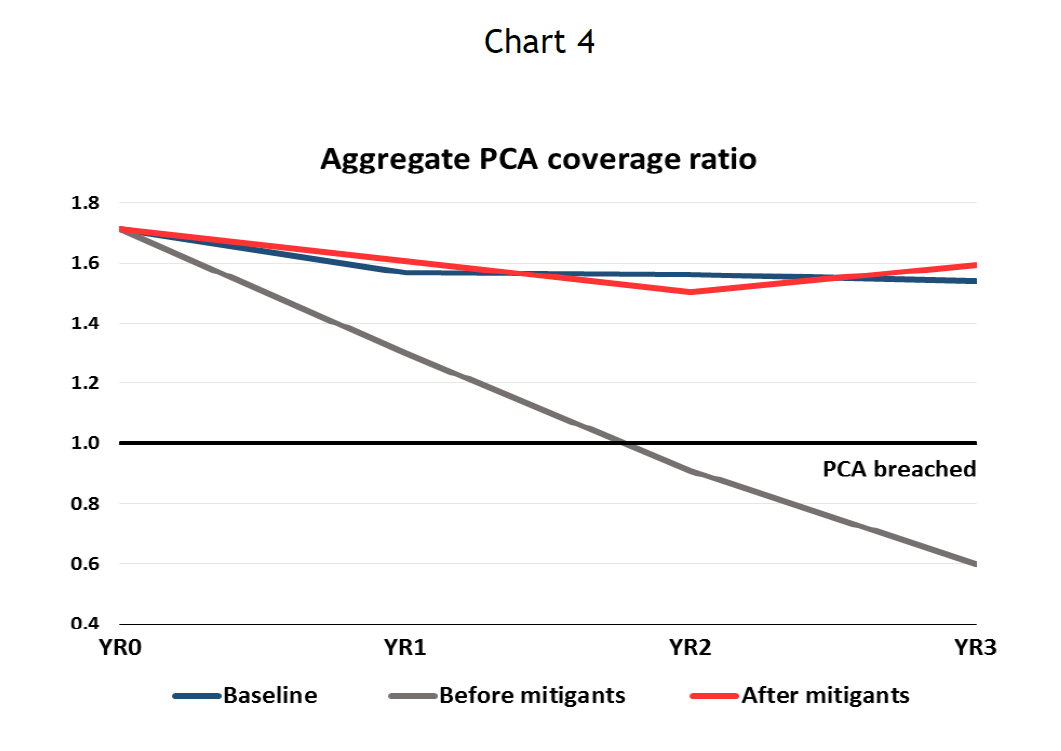

The aggregate capital base and PCA movements impacted regulatory capital coverage ratios, shown in Chart 4 below. Before mitigants the insurers in aggregate breached PCA just before the end of Year 2. Again, this was expected due to the severity of the scenario. Aggregate PCA coverage returned to just above baseline by the end of Year 3 after management actions were employed.

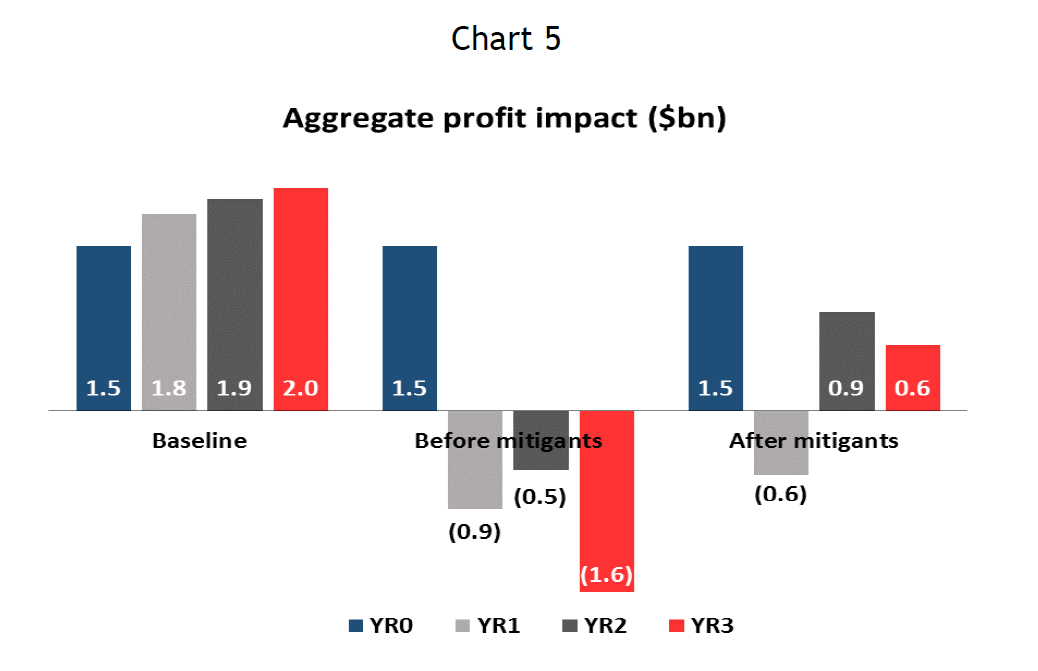

Chart 5 shows the impact on profitability. Without allowing for management actions, those involved in the stress test recorded a combined loss of some $900 million in the first year of the scenario and this grew to $1.6 billion by the end of Year 3, prior to employing management actions. Profitability improved once insurers were able to factor in the application of various mitigation strategies, including repricing, but unsurprisingly given the extent of the adversity, this would be insufficient to return the industry to anything like the baseline position.

Key insights

The feasibility of the management actions employed to restore capital was a key focus and this brings me to the main insights of the stress test.

Insurers responded to the stress scenario with a range of management actions. The most common actions were premium rate increases, reduction or suspension of dividends and capital injections. As a general observation, those insurers with more diversified business models had more options for mitigating the stress scenario than those, for example, with more concentrated product sets. Some took only one or a few management actions to restore capital, while others were able to (or chose to) access a greater range of actions.

In assessing feasibility we took into account the extent to which these actions can be reliably called on and the associated ease and timing of the effects. We also focussed on the rationale provided. Most insurers were able to offer sufficient justification that their plans would be achievable, but we highlight the need for Boards and senior management to understand any constraints attached to these actions, including implications for shareholders, policyholders, competitors and market capacity.

As an example, premium rate increases are an accepted and logical response to increased claims activity for insurance companies. But repricing poses challenges such as the speed in which to expect benefits and ease of implementation. Another difficulty is understanding how competitors would be responding to both the scenario in general and their own specific business needs. In this stress test, not all insurers opted to raise premiums. The impact on customer and competitor behaviour in this circumstance is therefore hard to predict.

As with past stress tests, each participant did not have a line of sight over responses by others and therefore needed to make a number of assumptions. This limitation is a feature of stress testing and places importance on the process and the decision-making framework within the confines of the scenario. To return to my earlier point, it also illustrates why we are reluctant to see stress testing evolve into a pass/fail exercise.

Another observation is the extent to which insurers sought external capital support, from either the market or their parent. Once again, not all insurers with that option chose to exercise it. Some relied on actions they could take on their own without external support. The cautionary word to insurers is that while the rationale for seeking support was generally reasonable, the extent to which new capital can be relied upon under duress (and in particular, if the stress scenario had a global reach) needs to be a continued conversation, with limitations acknowledged and mitigated by alternative arrangements.

Finally, while dividend reductions or suspensions were a common response, the patience of the shareholders and the impact on market confidence needs to be taken into account, particularly in such a prolonged stress period.

One of the outcomes of the stress test was that it illuminated the difficulties with disability income insurance. We in APRA are increasing our focus on this line of business, as part of our work on claims management practices with group risk insurers and superannuation trustees. We know the industry is working towards improving terms and conditions, pricing and other structural changes and we welcome these responses. The challenge here though is to find the right balance between affordability and sustainability.

The impact of the stress scenario on assets, for most, was not as severe as that for the liability book. This was expected, given the extent to which insurers have de-risked their investment portfolios since the global financial crisis. However, for some, the holding of higher growth assets is critical to fulfil obligations with guarantees attached. In these cases, insurers need to be confident that any resulting asset mix or hedging adjustments could be effectively employed within an environment of significant investment market decline. Clarity here is difficult and over-confidence should be avoided under such conditions.

Another insight relates to the setting of assumptions. While APRA set a number of prescribed parameters for the stress test, we left some open for insurers to set themselves. These were generally those that were difficult to quantify and subject to greater judgement, such as mortality, trauma, new business, expenses and lapse rates. The adjustments chosen by insurers for these assumptions varied widely, as did their rationale.

Some assumed increased lapse rates in response to premium rate hikes, others assumed no change. Some assumed an increase in mortality rates, largely from the tragic increase in suicide that can accompany economic downturns.

Our view is that, as long as the assumptions were accompanied by sufficient and reasonable analysis and justification, varied approaches and outcomes are not necessarily a bad thing. As I said earlier, the uncertainties of competitor and consumer behaviour makes prescription in this area difficult. However, we do note that some insurers erred on the side of conservatism more than others and this approach should be validated against risk appetite. Clearly, an overly optimistic approach to assumptions can mask the potential ultimate impact, just as an unduly pessimistic approach might – the onus is on insurers to get this balance right. But stress testing is ultimately about providing comfort that the downside is covered, so erring on the side of caution is probably a wise course.

Let me turn now to our observations regarding stress testing governance and modelling capability. Remember this was a key focus for the exercise. Prior to rolling out the scenario, APRA met with each participant to assess their readiness to conduct the stress test. The observations at the time were mixed, but overall we felt that the insurers would need to make improvements, including in some cases the procurement of resources and establishment of infrastructure, processes and procedures to do the stress test adequately.

We were therefore pleased to see insurers take on the exercise seriously, some of which adjusted or adopted more robust processes, evidenced through the submissions and in post-stress test meetings with participants. In some cases, insurers who voiced a reluctance or concern for conducting the exercise, eventually embraced it as useful and informative for their business.

I said at the outset that adopting a whole-of-business approach was considered better practice and we found that most insurers did so, seeking input from all parts of the business in workshop environments as the scenario played out, careful not to adopt perfect foresight.

We found submissions to Boards and senior management varied from comprehensive to less so and have communicated our observations with each of you. We encourage those on that latter end of the scale to improve the reporting of insights to Boards. This helps facilitate a more informative discussion on the risks the stress test may have revealed and any implications for the business.

Moving now to capital, there will be many who would expect an absolute view on whether the industry is resilient to this type of stress. While the initial impact of the scenario itself was severe, the stress test outcomes demonstrated that with reasonable management actions the industry participants could restore capital. However, as with all stress tests, the scenario was theoretical, conducted under laboratory-type conditions. Parameters were prescribed in advance and there was time to respond and consider options in an orderly fashion. As we know, this will not occur in reality. Once a stress hits the impact will be more immediate and will test even the most well-prepared insurers. And unlike a hypothetical stress scenario, responding to a real world stress involves much less visibility of how the scenario will play out into the future. The complexities and uncertainties of markets, customers, competitors and other environmental factors would be different than those prescribed for this exercise. And importantly, the mitigating actions proposed may not necessarily have the impact expected for recovery in real time.

Such uncertainty emphasises the importance of recovery planning and APRA has increased its expectations in this regard. Recovery planning is inherently linked to stress testing and we must ensure that the insurance industry remains vigilant, has well considered actions to deal with adversity and can exercise those actions effectively if needed.

So, the industry can expect more, not less, in terms of stress testing. We expect to hold such exercises regularly, with a reduction in time to undertake the stress test likely as resource capacity and modelling capability improves.

The multi-scenario, multi-year approach is favoured by APRA but we will consider greater prescription next time in some areas (e.g. such as whether insurers assume the stresses to be temporary or permanent) to foster stronger comparability across participants, and less prescription in the setting of criteria for before and after mitigating actions, which created undue complexity.

At this stage, we expect to hold another comprehensive industry stress test in 2018 (although in the intervening period we may follow a similar path as we did with ADIs and set a common scenario for inclusion in ICAAPs). In the meantime, there is no reason why insurers – whether they participated in the stress test or not – shouldn’t get on with it themselves.

Conclusion

To conclude, this was APRA’s first comprehensive industry stress test for the life insurance sector. Not all were involved, but we expect to expand future stress tests to include other insurers as we evolve our approach in this area. I make this latter point to emphasise that we in APRA are also on a learning curve when it comes to stress testing.

The stress test was not without its challenges, but it was highly worthwhile. Not only did it shine a light on areas of concern, such as disability income insurance, it reinforced and set expectations for continued advancement of stress testing capabilities in the industry.

If we are to be confident in a sector that can withstand adversity, insurers need to boldly think of those events that could hit them without warning, put themselves through a rehearsal and build from that exercise stronger resilience.

The community expects financial institutions to be there to support them in good times and – particularly in the case of insurance – bad. It is a foundation of community trust and confidence that the insurance sector is able to meet its commitments at the time when they are most needed.

I thank all of you for your involvement in this stress test – by participating, you have allowed learnings to be shared for the benefit of the wider industry and ultimately the policyholders you insure.

Thank you.

The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) is the prudential regulator of the financial services industry. It oversees banks, mutuals, general insurance and reinsurance companies, life insurance, private health insurers, friendly societies, and most members of the superannuation industry. APRA currently supervises institutions holding around $9.8 trillion in assets for Australian depositors, policyholders and superannuation fund members.