Individual challenges and mutual opportunities

Wayne Byres, Chairman - Keynote address at Customer Owned Banking Convention, Brisbane

Good morning everyone, and thank you to COBA for the invitation to be part of this year’s Customer Owned Banking Convention.

The landscape in which banking services are being provided continues to evolve rapidly. Some of the changes are regulatory, and so I’ll talk this morning about a few things in APRA’s bailiwick, but I also want to discuss a couple of the broader influences on the ability of mutual organisations to thrive and compete in the Australian banking system of today and the future.

The changing industry composition

Before looking ahead, though, I’d like to briefly look back. If you have been involved with the mutual banking sector for some time, you will know that the composition of the industry has changed markedly. Since 1999, the number of ADIs in Australia has halved (Table 1), and that consolidation has occurred primarily in the mutual sector. By number, mutual ADIs made up four-fifths of the industry; that proportion is now just on half.

| Sector | 1999 | 2004 | 2009 | 2013 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domestic (including mutual) banks | 15 | 14 | 14 | 21 | 33 |

| Credit unions and building societies | 241 | 188 | 125 | 95 | 58 |

| Foreign bank subsidiaries | 11 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 7 |

| Other ADIs | 4 | 7 | 8 | 7 | 6 |

| Foreign bank branches | 25 | 28 | 35 | 40 | 44 |

| Total ADIs | 296 | 247 | 191 | 171 | 148 |

Furthermore, the increasing trend for credit unions and building societies (CUBS) to convert to mutual banks means that, by number, CUBS now account for a touch under two fifths of ADIs. Although the community reportedly dislikes banks, there’s no lack of interest in being branded one – it seems the cachet outweighs any disdain. And given the Government’s proposed amendments to the Banking Act 1959 to allow all ADIs to brand themselves as banks, the trend will likely continue. One important by-product of that, however, will be the prevalence, and community understanding of the concept, of a credit union or building society will further diminish – a challenge that those of you who choose to retain the branding are no doubt conscious you will need to deal with.

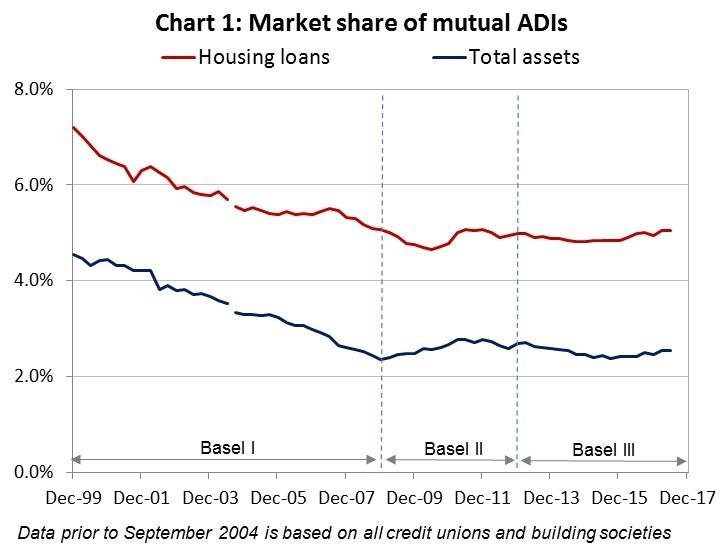

In terms of market share, mutual ADIs account for just over 2½ per cent of industry assets (Chart 1). While this is down from about 4½ per cent in 1999, it is worth noting the totality of the decline in share occurred prior to 2009. In the post-crisis period, mutuals have successfully held their own with a market share that has hovered around a relatively constant level.

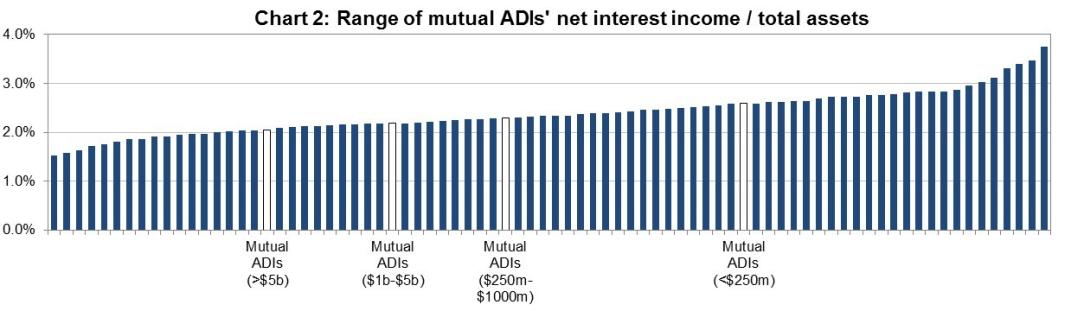

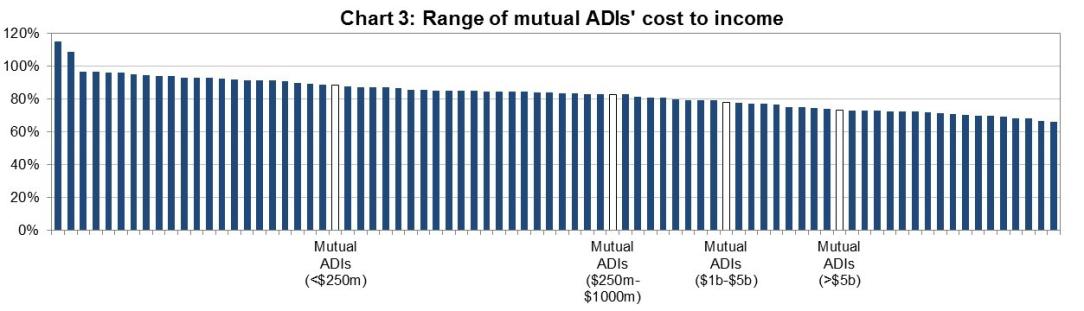

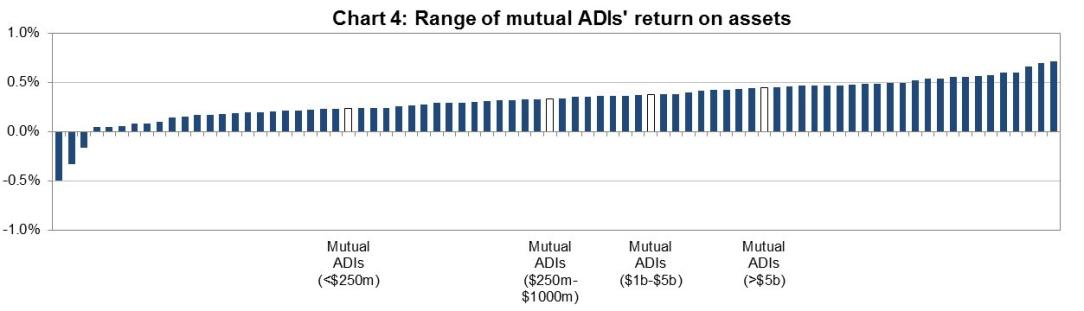

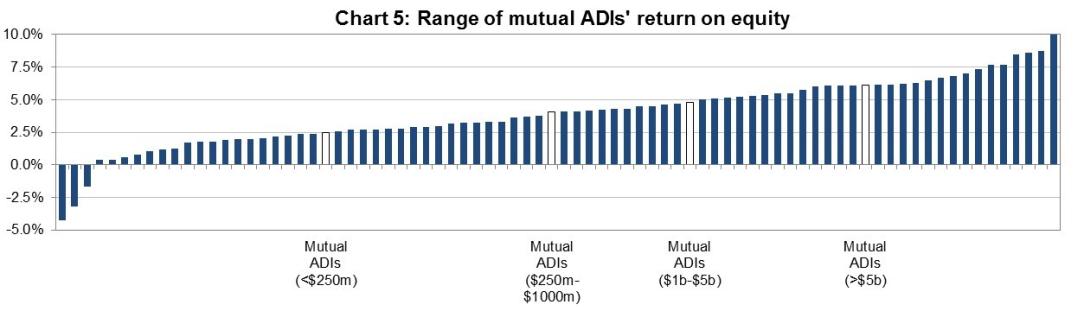

Consolidation in the mutual sector over the past two decades has often reflected the search for economies of scale, with a view to enhancing mutual ADIs’ competitive position. There is certainly evidence that scale economies exist within the mutual sector: larger mutuals tend to have materially lower cost ratios. Through that, they are able to achieve higher profitability and growth in capital (Charts 1-4).

Nevertheless, costs in the mutual sector remain relatively high. Measured relative to assets, mutuals generate higher net interest income, and higher total income, than the four major banks that dominate the industry. Unfortunately, the much higher cost base more than offsets that advantage (Table 2). This is obviously an important issue for prudential regulators like APRA, since profitability is a mutual’s primary source of new capital strength. It is also important in the broader debate on competition. As things stand, a high cost base constrains the ability of mutual ADIs to generate returns that are sufficient to fund balance sheet growth at above system levels – a precondition for growing market share. I readily acknowledge that mutuals do not have the same profit motive as shareholder-owned institutions. But, mutual or not, retained earnings provide the key source of new growth potential.

| Cost | Majors | Mutuals |

|---|---|---|

| Net interest income | 1.7% | 2.1% |

| Other income | 0.7% | 0.6% |

| Total income | 2.5% | 2.7% |

| Operating costs | -1.2% | -2.1% |

| Bad debt expenses | -0.1% | -0.0% |

| Profit before tax | 1.2% | 0.6% |

| Tax | -0.4% | -0.2% |

| Profit after tax | 0.8% | 0.5% |

Tackling costs is therefore critical to being a stronger competitive force in the Australian banking system. If the mutual sector could just halve the cost gap with the major banks, for example, it would potentially be able to generate a very similar return on assets, changing the competitive dynamics quite considerably. To be clear, that does not automatically mean more consolidation is the answer, but at the least I would encourage you to work collaboratively and cooperatively on ways to generate the scale efficiencies likely to be needed to really change the competitive landscape.

The impact of technology

Technology-driven innovation is changing almost every industry, and the financial sector is no different. Operating models are being transformed as entities embrace automation, digitisation and the internet to achieve efficiencies, improve information exchange and enhance customer experience.

With a couple of important caveats, technology offers one possible means to substantially reduce industry costs. Particularly for smaller players, new technology potentially offers the use of commoditised, scalable and cost-effective services/platforms. Data analytics provide the potential for greater customer engagement and anticipation of customer needs. Social media and other online platforms can help promote a stronger community culture, potentially an important differentiator for customer-owned entities. And there are new technology offerings with the potential to improve risk management practices and substantially reduce the compliance burden.

Of course, these opportunities come with challenges.

The first is the need for investment. Investment in new platforms and means of servicing customers is not optional if a banking business wishes to be competitive. One timely example is the imminent arrival of the New Payments Platform. The NPP will open up a range of new, fast and innovative payments services to individuals and small business customers that are the core franchise of the mutual banking segment. It won’t be surprising if these services generate strong demand as customer awareness grows of the ability to make and receive payments in real time, without the hassle of BSB and account numbers, and with an expanded messaging capability. But being ready to offer new payment services requires new infrastructure and risk controls (such as real-time fraud detection) that do not come cheap. And for small ADIs, individually developing that infrastructure is unlikely to be optimal - collaborative efforts make much more sense.

The second challenge is that the increasingly digital business that customers demand also expands the attack surface for cyber-adversaries to exploit. Australia avoided the worst of the WannaCry and Not-Petya ransomware outbreaks earlier this year, but there is no room for complacency because those who wish to cause damage continue to increase the sophistication of their tools of trade, and are constantly searching out the weakest link. Unfortunately, there is no response except on-going vigilance, good housekeeping (eg up to date patching), continuous improvement and – again – investment. It is also another reason for collaboration, in sharing information on the latest threats and the best responses to them.

So new technology is a double-edged sword. For smaller ADIs, it offers an opportunity to compete more effectively than was ever possible in a geographically-constrained, bricks-and-mortar world. But it also requires substantial investment, both in capabilities and risk management. A key issue is therefore how to generate the necessary returns to cover the required investment spending that the transition to a digital world requires. To repeat my earlier point, collaboration across the mutual sector to find collective solutions is likely to be essential to overcome this challenge.

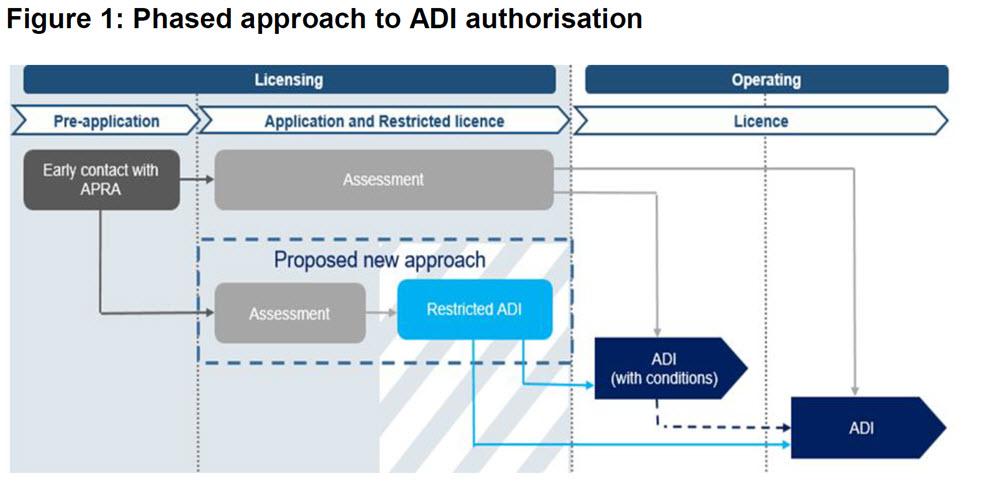

Technology also opens the potential for new competitors. Acknowledging this, APRA recently announced a revamp of its approach to licensing new entrants to the ADI industry. Broadly, we did two things. First, we reorganised ourselves to create a centralised licensing team, which will be better placed to handle the increasingly diverse range of applicants that are seeking to engage with us. And second, we flagged a new phased approach to licensing. The phased approach is designed, without unduly jeopardising overall entry standards, to make it easier for new applicants with innovative or otherwise non-traditional business models to navigate the licensing process.

A number of potential applicants – varying from fintech companies to niche lenders – are already in discussions with us about taking advantage of the new phased approach. Most of these new entrants are looking to enter the retail/SME banking market, albeit initially with fairly narrow product offerings. Nevertheless, while not all will be successful, the UK experience has been that the phased approach has facilitated new entrants, which have been able to win market share and make solid profits with a relatively low cost base. A feature of their success has been the ability to adopt leading edge technology, and avoiding the legacy costs that many incumbents have been unable to shed.

Capital

Along with changes to licensing, we made two important announcements in July in relation to capital that I’d like to briefly touch on.

First, we set out our assessment of the minimum capital requirements necessary for the banking sector to have ‘unquestionably strong’ capital ratios.

Consistent with the recommendation of the FSI, we applied the ‘unquestionably strong’ standard to all ADIs. There seemed little value, and quite some risk, in an approach which, for example, only applied the concept to larger ADIs: that may have had smaller ADIs perceived to be ‘questionably strong’. We did recognise, however, that differences in existing capital standards needed to be accommodated in any adjustments. We concluded that, to achieve a standard that unquestionably delivered strong capital ratios, the minimum requirements for IRB banks should increase by 150 basis points, but only a 50 basis point increase in minimum requirements was warranted for ADIs using the standardised approach.

Given most mutual ADIs have capital well in excess of existing minimums, the increase in requirements will in most cases be easily accommodated though existing capital surpluses.

We also flagged that increases in capital will closely align with measures to target higher risk residential mortgage lending, as well as the high concentration in housing within the Australian banking system. This issue does not seem to have received the attention it deserves within the mutual sector, so I want to highlight one particular point today: that the materially larger adjustment to IRB capital requirements relative to standardised capital requirements serves to reduce further the remaining residual difference in mortgage lending risk weights, delivering on the second recommendation of the FSI. Although the exact details of the new risk weight functions are still to be settled, the impact of future capital differentials on pricing will likely end up quite small. As a result, as a major influence on competition, the issue has largely been negated.

Our second announcement concerned allowing mutual ADIs to issue mutual equity instruments (MEIs) as an additional source of CET1 capital beyond retained earnings.

Not surprisingly, industry reaction to the proposal has been positive, albeit there are a range of technical details that we have been asked to think further about. We are working through this feedback, and hope to issue a final framework within the next month or so.

We are in some ways ‘reinventing the wheel’ in facilitating direct issuance of MEIs. MEIs are not dissimilar in concept to non-withdrawable shares. Our new framework has therefore been guided to some extent by the fact that, as those of you with long memories will recall, non-withdrawable shares played a critical role in the rise, and demise, of the Farrow group of building societies in the early 1990s. David Habersberger QC, who conducted an inquiry into the Farrow collapse for the Victorian Government, found that the instruments were missold, mismanaged, and poorly regulated. While the regulatory framework has strengthened since then, we have been mindful of Habersberger’s findings in designing the MEI framework.

One challenge for those issuing MEIs will be to think carefully about the potential investor base and cost of the instrument. MEIs should pay a return that reflects the risk of an equity investment. They can only be issued cheaply if investors underprice or misunderstand that risk. But if the cash distribution rate on MEIs paid by the ADI is higher than an ADI's existing return on equity – which, given the data earlier, it may well be for many mutuals – issuing MEIs will risk diluting future earnings and stunt long-term growth capacity.

So MEIs will not work for everyone, and are certainly not a panacea for significant new growth capacity for the sector. We don’t want the sins of the past repeated but, when used wisely, MEIs can be a useful addition to a mutual ADI’s capital structure and we are therefore happy to accommodate them within the regulatory framework. We are also keen for the industry to work with us on developing some boilerplate documentation for MEIs, rather than developing bespoke offerings. A standardised instrument would significantly streamline and shorten the approval process for MEI issues, and potentially also help a market for MEIs to develop.

Graduated approach

One of APRA’s constant challenges is balancing two competing demands: a desire for a regulatory framework that appropriately differentiates across the diversity of ADIs, and (simultaneously) a desire to avoid differences in regulation creating competitive inequalities when different classes of ADIs compete against each other. Put more simply, there are few advocates for a ‘one size fits all’ approach, but equally everyone wants a level playing field.

In practice, we apply varied regulatory requirements according to circumstances. The four major banks operate under a similar (and quite complex) regulatory framework, while most small ADIs utilise a quite different (and simpler) version. But in between there is a degree of tailoring, designed to match regulatory requirements with ADIs’ material risks and capabilities. In terms of our mandate, we believe this delivers the best level of financial safety and stability, while still being mindful of considerations of competition, efficiency, contestability and competitive neutrality. The right balance between consistency and proportionality is always a fairly nuanced judgement.

With a major review of most parts of the capital framework shortly to occur, we are giving thought to a more systematic application of the framework in a graduated manner. Of interest to many in this room, we are contemplating a more proportionate and better tailored framework for small ADIs, through what we are calling ‘a simplified framework’. Conceptually, a simplified framework would remove complexity and cost for small ADIs that fall below a size threshold and operate a fairly simple business model (trading activities would, for example, preclude an ADI from using the simplified framework).

At this stage, APRA is not proposing to simplify the standardised capital framework for credit risk. Credit is the most material risk for almost all ADIs, so a sufficiently risk sensitive approach is justified for both safety and competitive equity reasons. But to give you a couple of examples of our thinking, a simple flat capital add on to risk-weighted assets for operational risk could completely replace the current factor based calculation based on business lines. In the case of disclosure, a centralised publication, by APRA, of key risk metrics on behalf of small ADIs could replace the current requirement for ADIs to regularly produce and publish material themselves.

The challenge for the industry in heading down this path is that, even with a calibration of the framework that is consistent between approaches overall, there will be differences of detail – indeed, that is the very point of the exercise. Those differences of detail will, however, inevitably create competitive and cost differences, at least at the margin, between ADIs subject to the different approaches. The more we make any simplified framework simple and low cost, the greater that risk becomes. We will be keen to hear the mutual sector’s views on the trade-off as we develop this proposal.

Housing lending standards

Before I conclude today, I want to take a short detour to the subject of residential mortgage lending standards.

Earlier this year, we announced further measures to reinforce prudent standards across the industry. We did this because, in our view, risks and practices were still not satisfactorily aligning. We remain in an environment of high house prices, high and rising household indebtedness, low interest rates, and subdued income growth. That environment has existed for quite a few years now, and one might expect a prudent banker to tighten lending standards in the face of higher risk. But for some years standards had, absent regulatory intervention, been drifting the other way. Indeed, if we look back at standards that the industry thought important a decade ago, we see aspects of prudent practice that we are trying to re-establish today.

The erosion in standards has been driven, first and foremost, by the competitive instincts of the banking system. Many housing lenders have been all too tempted to trade-off a marginal level of prudence in favour of a marginal increase in market share. That temptation has, unfortunately, been widespread and not limited to a few isolated institutions – the competitive market pushes towards the lowest common denominator. The measures that we have put in place in recent years have been designed, unapologetically, to temper competition playing out through weak credit underwriting standards.

Since we have been focussing on lending standards, APRA’s approach has been consistently industry-wide: the measures apply to all ADIs, albeit with additional flexibility for smaller, less systemic players around the timing and manner in which they have been expected to adjust practices. There is no reason, however, why poor quality lending should be acceptable for some ADIs and not others, or in one geography and not others. Prudent standards are important for all.

At a macro level, our efforts appear to be having a positive impact. As I have spoken about previously, serviceability assessments have strengthened, investor loan growth has moderated and high loan-to-valuation lending has reduced. New interest-only lending is also on track to reduce below the benchmark that we set earlier this year. Put simply, the quality of lending has improved and risk standards have strengthened.

We would ideally like to start to step back from the degree of intervention we are exercising today. Quantitative benchmarks, such as that on investor lending growth, have served a useful purpose but were always intended as temporary measures. That remains our intent, but for those of you who chafe at the constraint, their removal will require us to be comfortable that the industry’s serviceability standards have been sufficiently improved and – crucially – will be sustained. We will also want to see that borrower debt-to-income levels are being appropriately constrained in anticipation of (eventually) rising interest rates.

These expectations apply across the industry, to large and small alike. Pleasingly, the industry is moving in the right direction to achieve that. Improved serviceability standards are being developed, and policy overrides are being monitored more thoroughly and consistenly. The adoption of positive credit reporting, which APRA strongly endorses, will remove a blind spot in a lender’s ability to see a borrower’s leverage. Coupled with the higher and more risk-sensitive capital requirements that I mentioned earlier, these developents should – all else being equal – provide an environment in which some of our benchmarks are no longer needed. The review of serviceabilitiy standards across the small ADI sector that we are currently undertaking will help inform our judgement as to how close we are to that point.

Concluding remarks

To return to where I started, the banking environment is changing rapidly. For mutuals, there are a number of regulatory initiatives occurring that will help your competitive position in the face of that change: capital requirements for mortgage lending relative to the largest banks have been adjusted, a new type of capital instrument will soon be available, and we are exploring the potential for a simpler and low cost set of requirements for the smallest ADIs. The Government has also proposed to make it easier for all ADIs to use the word ‘bank’.

But the impact of these changes will, in my view, be marginal at best in the face of the major technological changes impacting the business of banking. The digital revolution will challenge small ADIs’ ability to stay close to the forefront in retail product offerings, as well as bring new competitors with lower-cost business models. With that in mind, working collaboratively within the mutual sector, which COBA and its predecessor bodies have long promoted, and which APRA certainly supports, will be even more important in the future. I encourage you to embrace those opportunities as a means of meeting the challenges that lie ahead.

The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) is the prudential regulator of the financial services industry. It oversees banks, mutuals, general insurance and reinsurance companies, life insurance, private health insurers, friendly societies, and most members of the superannuation industry. APRA currently supervises institutions holding around $9.8 trillion in assets for Australian depositors, policyholders and superannuation fund members.