Is the capital benefit of being an advanced modelling bank justified?

The role that capital plays in protecting depositors has never been more evident than following the swift collapse in March this year of Silicon Valley Bank and the takeover of Credit Suisse. Like peer regulators around the world, APRA’s remit is to protect depositors and promote financial system stability by requiring banks to hold sufficient capital to withstand shocks and absorb losses. One of the lessons underscored by these international bank failures is the need for continuous, rigorous review of regulatory requirements to ensure they are working the way they need to.

While APRA continues to analyse the circumstances of those events, significant revisions to its bank capital framework became effective from 1 January this year. A predominant feature of the revised framework targets credit risk – still the largest financial risk for banks. Credit risk refers to losses arising from borrowers failing to repay their loans and other financial obligations. APRA permits two main approaches to calculating capital for credit risk: the standardised approach and the internal ratings-based (IRB) approach, the latter of which is currently only approved for use by six of the largest banks in Australia.

The gap between the capital requirements under the different methods has led to some market participants questioning whether IRB banks have a financial advantage, particularly in relation to residential mortgages.

Not only is the magnitude of the gap (in capital required) between the IRB and standardised approaches often misunderstood, APRA argues that differences in capital requirements between the two methods are both intentional and appropriate. With the introduction of the new credit risk capital framework this year, APRA has even stronger mechanisms in place to prevent excessive divergence in capital requirements and limit impacts to competition in the Australian banking system.

Understanding the credit risk capital framework

APRA’s capital adequacy framework for banks prescribes a set of rules so that capital – the cornerstone of a banking system – does not run out. The requirements of the new framework are largely based on the internationally agreed framework developed by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision with some modifications for Australian circumstances and risks.

Under the capital framework, banks are allowed to use two approaches for calculating credit risk capital requirements:

- a standardised approach, which is simple, conservative and caters for a wide range of banks and portfolios; and

- an advanced approach, also known as the IRB approach, which seeks to better align capital with risk by permitting banks to use their internal risk models to calculate capital requirements.

How are credit risk capital requirements calculated?

The minimum capital requirement for credit risk is basically the minimum capital adequacy ratio multiplied by credit risk-weighted assets. The minimum capital adequacy ratio is prescribed by APRA and comprises an internationally agreed minimum ratio plus capital buffers to provide an additional cushion to absorb losses.

Credit risk-weighted assets are loans and other assets that are weighted (that is, multiplied by a percentage factor known as a “risk-weight”) to reflect their risk of loss to a bank. The higher the credit risk, the higher the risk-weight, and therefore the higher the credit risk-weighted assets.

Banks must hold a minimum amount of capital to cover the risk of unexpected losses from lending and other business activities

Standardised approach

Under the standardised approach, banks must use a common set of risk-weights prescribed by APRA in the risk-weighted assets calculation. For example, standardised risk-weights for residential mortgage lending at low loan-to-valuation ratios (LVRs) start from 20 per cent, while risk-weights for higher risk, unsecured business lending range from 75 to 100 per cent.

Standardised risk-weights are calibrated at a conservative level because they are less precise and apply to a wide range of banks. This calibration ensures that standardised banks are adequately capitalised overall. While risk-weights are generally more conservative, there is a lower burden on standardised banks in terms of other supervisory requirements including data reporting.

Internal ratings-based (IRB) approach

Under the IRB approach, banks are permitted to use their internal risk models to produce estimates of credit risk such as the likelihood of borrowers not repaying their loans, and what loss that might cost the bank. The risk estimates are then input to risk-weight formulas prescribed by APRA to calculate credit risk-weighted assets.

The risk-weights under the IRB approach are tailored to the risks of an individual bank and are more precise than standardised risk-weights (that is, sensitive to a wider range of portfolio risk characteristics). Therefore, the IRB approach is a more accurate measurement of risk which enables a better alignment of capital to that risk.

To use the IRB approach, banks must have very good historical data, a sophisticated risk measurement framework, develop advanced internal modelling capabilities, and undergo a rigorous assessment process in order to be accredited by APRA. IRB banks are subject to more stringent regulatory requirements and more intensive ongoing supervision than standardised banks.

Two approaches to calculating credit risk capital requirements

Internal ratings-based (IRB) versus standardised capital requirements: how do they compare?

In principle, capital requirements under the IRB approach can be higher or lower than the standardised approach depending on the underlying risk characteristics of a specific exposure. On average, the capital framework has been calibrated such that IRB capital requirements tend to be lower than standardised capital requirements. This calibration has two policy objectives:

- to encourage investment by banks in advanced modelling capabilities and associated technology, data and specialist skills. Such investment is significant and ongoing but provides substantial risk management benefits such as:

- improving a bank’s ability to identify the risk profile of its lending and other business activities;

- facilitating risk-based and evidence-based decision-making and portfolio management;

- ensuring risk is properly priced;

- supporting financial innovation and the bank’s ability to respond to market changes and changes in risk profile; and

- to enable banks to more accurately allocate capital for risk.

Yes, there are differences, but there are also safeguards

APRA recognises that, while the IRB approach is accessible to any bank that can model its risks to an acceptable standard, IRB accreditation is not cost-effective for some smaller banks given their lack of scale and diversification. Therefore, while differences between the IRB and standardised approaches are embedded in the capital framework by design, there are also in-built safeguards to ensure that any capital benefit for IRB banks is not excessive and does not unfairly disadvantage standardised banks.

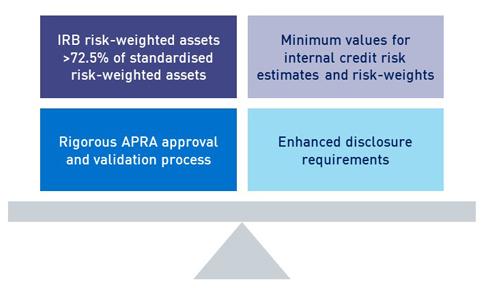

The new capital framework has introduced further mechanisms to prevent excessive divergence between IRB and standardised capital requirements and limit any detrimental effect on competition between IRB and standardised banks. These include:

- additional constraints on the IRB approach including minimum values for IRB residential mortgage risk-weights and overall IRB risk-weighted assets;

- higher capital buffer requirements for IRB banks compared to standardised banks;

- higher risk-weights for higher risk lending under the IRB approach;

- lower risk-weights for lower risk residential mortgage lending and small business lending under the standardised approach; and

- enhanced disclosure standards, which require IRB banks to calculate and report risk-weighted assets under both the IRB and standardised approaches.

Safeguards in the framework ensure that any capital benefit for IRB banks is not excessive and does not unfairly disadvantage standardised banks

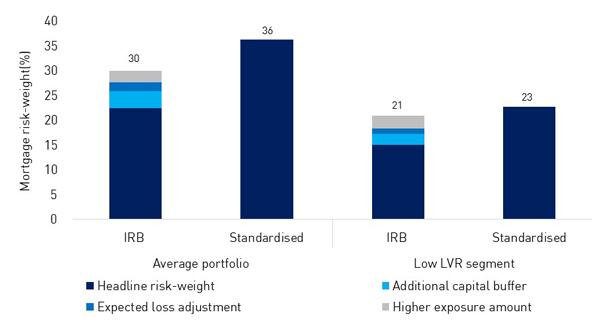

To further illustrate how the capital framework affects different banks, the figure below compares the average risk-weight for residential mortgage loans under both the standardised and IRB approaches. The difference in headline risk-weights across the portfolio is 14 per cent, but headline risk-weights do not provide the complete picture of overall capital requirements. There are other differences between the two approaches which mean the real difference in capital requirements is much narrower than implied by a simple comparison of headline risk-weights. When taking all the elements of the two methodologies into account, the gap between IRB and standardised capital requirements for residential mortgage loans reduces to 6 per cent. For loans with an LVR of less than 60 per cent, the difference is even smaller at 2 per cent.

APRA has estimated that the average pricing differential for residential mortgage loans due to differences in IRB and standardised capital requirements is 0.05 per cent. This pricing differential is modest and demonstrates that the capital framework has effective mechanisms in place to prevent excessive divergence between the two approaches.

Real differences in IRB and standardised capital requirements are much narrower than implied by a simple comparison of headline risk-weights

Other material differences between the internal ratings-based (IRB) and standardised approaches

In addition to differences in the risk-weighted assets calculation, there are other material differences between the IRB and standardised approaches.

IRB banks have higher minimum capital adequacy ratios than standardised banks (otherwise, all else equal) due to an additional capital buffer requirement of 125 basis points.

IRB banks must make technical adjustments to their credit risk capital requirements that standardised banks are not required to make. For example, IRB banks must compare regulatory expected losses (derived from their internal estimates of credit risk) against provisions held for credit losses and deduct any shortfalls in provisions from the capital base, which increases overall capital requirements. Additionally, certain loans have a higher exposure amount due to higher percentage factors being applied (resulting in higher capital charges).

IRB banks are required to hold capital for interest rate risk in the banking book. There is no current equivalent requirement for standardised banks (although it is arguable that some part of the higher standardised risk weights might account for interest rate risk). Learnings from this year’s international bank failures are being incorporated into the capital framework for interest rate risk in the banking book.

There are higher operational costs from investing in and maintaining data and risk management systems to support the use of the IRB approach. This includes strict expectations relating to monitoring and validation of models, with regular adjustments to those models often necessary.

There are also differences in how standardised and IRB capital requirements change over time, including during periods of stress. Standardised capital requirements are generally stable over the economic cycle. In contrast, IRB capital requirements are more responsive to changes in risk as well as the cycle and will tend to increase while economic conditions are deteriorating and decrease during benign periods. This means that the difference in standardised and IRB capital requirements will also vary over the cycle and is likely to be smallest during periods of stress. APRA expects IRB banks to carefully manage additional volatility in their capital requirements through the cycle.

Conclusion

Fundamentally, differences between the IRB and standardised approaches reflect the expectation of more sophisticated risk management of larger, complex institutions. The differences seek to provide an incentive for banks to invest in advanced modelling capabilities, improve risk management frameworks and better align capital with risk.

APRA will continue to review the ongoing suitability of the broader capital framework, taking on board lessons of the recent international bank failures. For now, APRA has confidence that the current credit risk capital framework and the ongoing supervision of its entities, bolstered by recent adjustments, mean that the differences between the IRB and standardised approaches are justified and ultimately deliver on the goals of fair and equitable capital adequacy rules for Australian banks.

The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) is the prudential regulator of the financial services industry. It oversees banks, mutuals, general insurance and reinsurance companies, life insurance, private health insurers, friendly societies, and most members of the superannuation industry. APRA currently supervises institutions holding around $9.8 trillion in assets for Australian depositors, policyholders and superannuation fund members.