Banking on housing

Wayne Byers, Chairman - Australian Business Economists Lunchtime Briefing, Sydney

Thank you for the invitation to join you for lunch today. It is not unusual, particularly in Sydney, for the topic of conversation over a meal – be it at dinner table with friends, or a barbeque in the backyard - to turn to the subject of real estate. Today will be no different, although I intend to focus less on housing prices and more on housing finance.

Thank you for the invitation to join you for lunch today. It is not unusual, particularly in Sydney, for the topic of conversation over a meal – be it at dinner table with friends, or a barbeque in the backyard - to turn to the subject of real estate. Today will be no different, although I intend to focus less on housing prices and more on housing finance.

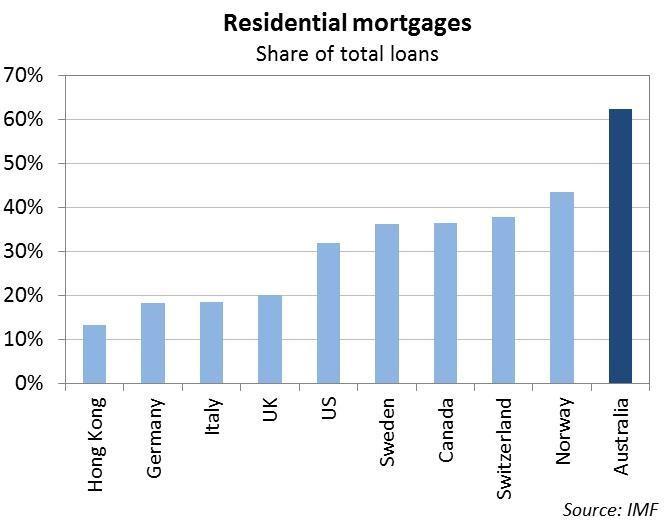

The Australian banking system is noteworthy for the predominance of housing loan assets. Lending for housing has traditionally been safe and profitable and, as a result, has grown to become the largest business line for many Australian banks. Building societies have, of course, always been focussed on housing, and over the past couple of decades credit unions have transformed themselves into housing lenders as well. Housing lending now accounts for around 40 per cent of banking industry assets, and a little under two-thirds of the aggregate loan portfolio. With such a concentration in a single business line, we are all banking on housing lending remaining ‘as safe as houses’.

A recap on recent supervisory actions

Lending for housing need not always be safe. As we know, housing lending was at the centre of the global financial crisis. Reckless lending, at teaser rates, by lenders with insufficient capital strength and who thought they had no real skin in the game, to borrowers with no real capacity to repay, and with everyone comforting themselves that housing prices could only go up, proved a fatal cocktail.

Those extremely poor practices – and the misallocation of credit that resulted – didn’t make it to these shores. But in a banking system such as Australia’s, there’s no room for complacency: the quality of lending for housing is too important not to be subject to a great deal of scrutiny.

In recent years, APRA has stepped up our examination of the lending practices and risk profiles of Australian housing lenders. For example:

- in 2011 and again in 2014, we sought assurances from the Boards of the larger authorised deposit-taking institutions (ADIs) that they were actively monitoring their housing lending portfolios and credit standards;

- in 2013, we commenced more detailed information collections from the larger ADIs on a range of housing loan risk metrics;

- in 2014, we stress-tested the 13 largest ADIs against two scenarios involving a significant housing market downturn;[1]

- also in 2014, we issued a Prudential Practice Guide on sound risk management practices for residential mortgage lending;[2] and

- at the end of last year, we wrote to all ADIs about the need to maintain sound lending standards, and established some benchmarks against which we would consider the need for further supervisory actions.[3]

These steps constitute a gradual ‘turning up of the dial’ in our supervisory intensity, in response to what we perceive as an environment of increasing risk. So what are the risks we see? I’ll talk about them at three levels: the broader conditions in which housing lending is occurring, some trends influencing the risk profile of housing loan portfolios, and finally current housing lending standards.

Housing lending conditions

Housing lending conditions are an important consideration in APRA’s work, but we can do little to influence them directly.

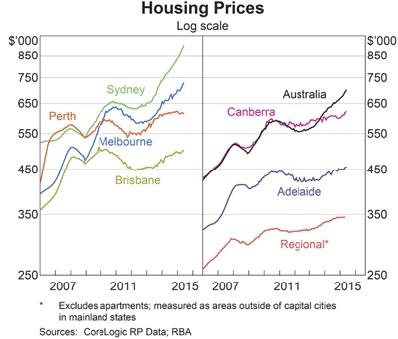

Any discussion on housing market conditions these days typically starts - and sometimes ends – with housing prices. It’s clear that Australian housing prices are high. On common metrics such as prices-to-incomes or prices-to-rents Australian housing prices are at the higher end of the spectrum, measured either historically or internationally. There are many reasons proffered for why this is: a strongly growing population, geographic and regulatory constraints on supply, the impact of lower inflationary expectations and financial deregulation, and taxation arrangements all feature prominently in explanations of the level of Australian housing prices.

In recent years, these metrics of housing prices have been high but relatively stable, although most recently they seem to be on the increase again. That has primarily been driven by the major cities of Sydney and Melbourne, where prices are growing quite quickly. We shouldn’t, however, allow the focus on the latest monthly growth rate in these two cities to distract us from the overall environment of high housing prices. It is not only these cities where, for example, housing price growth is outstripping the growth in rents.[4]

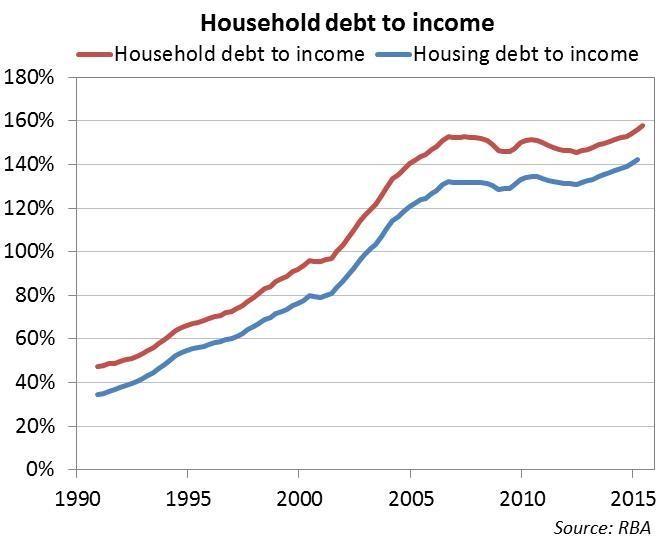

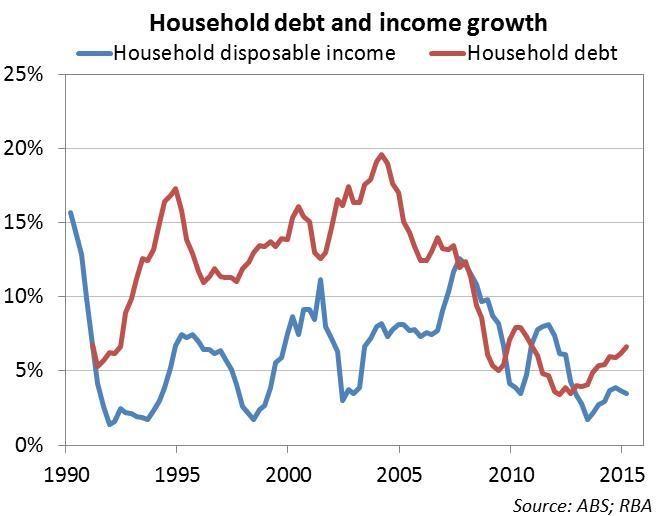

It is not surprising to find that high housing prices are accompanied by high household debt. As with housing prices, these debt levels are at the higher end of the spectrum. Furthermore, after plateauing for much of the past decade, the household debt-to-income ratio has begun drifting upwards again. Households still have a significant (and growing) net worth, as housing assets are increasing in value faster than debt. Nevertheless, the trends in overall level of debt bear watching.

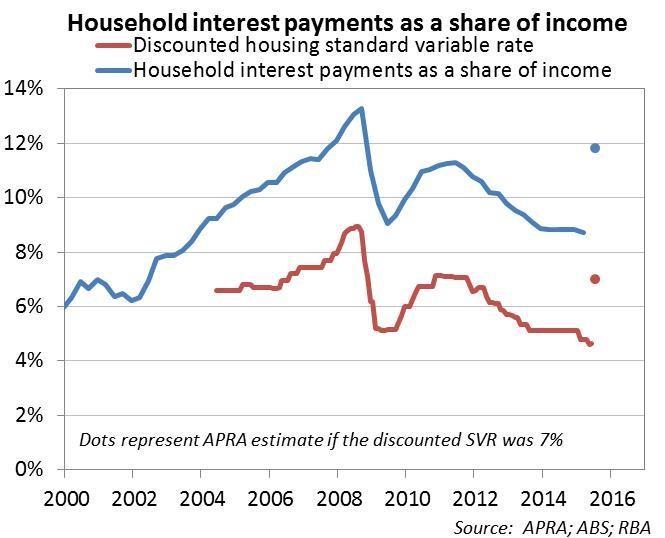

High and increasing levels of debt have been manageable for households because, amongst other things, interest rates are now at historically low levels. As a result, interest payments account for a lower share of household income than at any time since the financial crisis. Over a longer period, however, they do not necessarily look especially low. If housing interest rates returned to anything like long-term averages, the interest burden would begin to look quite high.

We are also in an environment of subdued income growth. Household income growth has been relatively low over the past couple of years, and is now broadly in line with underlying inflation – implying minimal growth in real terms, and limited capacity to support significantly higher debt levels.

To sum up, the environment for housing lending is one of relatively high house prices, high household debt, historically low interest rates, and subdued income growth. Against such a backdrop, APRA is certainly intensifying its scrutiny of portfolio risk profiles but, regardless, lenders should recognise the heightened risks and be doing likewise without too much prompting from us. There seems little to be gained from anything less than robust credit standards in the present environment.

Housing loan portfolios

Turning to loan portfolios, APRA’s concern has been that, in the face of ample credit and strong competition for new and existing customers for many years, there is the potential for a slow but steady erosion of credit quality. Lower credit quality portfolios, of themselves, may not necessarily be worrisome if the strategy is a conscious one, the additional risk is appropriately priced and managed, and adequate capital is held. That is really what much of our work has been designed to test.

We have spent quite some time looking into the broad trends in housing lending, and what they imply for the nature of risk within bank balance sheets. I’ll outline a few that have caught our eye. They are not the whole story – and will vary from lender to lender – but are important for understanding whether, in addition to the environmental factors I’ve mentioned, the industry’s risk profile is changing.

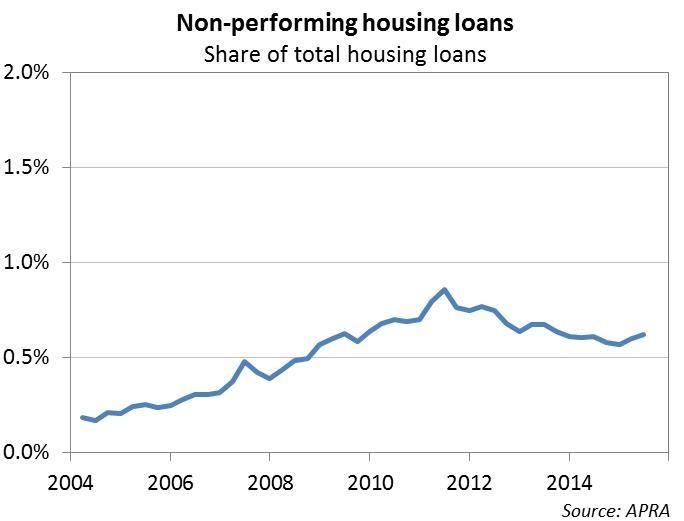

Non-performing loans are the usual starting point for any such analysis. In short, the picture seems fairly benign. Certainly, non-performing housing loans (primarily loans more than 90 days past due) remain somewhat above pre-crisis levels. On the other hand, they have steadily declined from their post-crisis peak, and are relatively low when compared internationally. However, this is a backward-looking measure and, given the absence of periods of adversity, is probably of limited value at present as an indicator of risk levels.

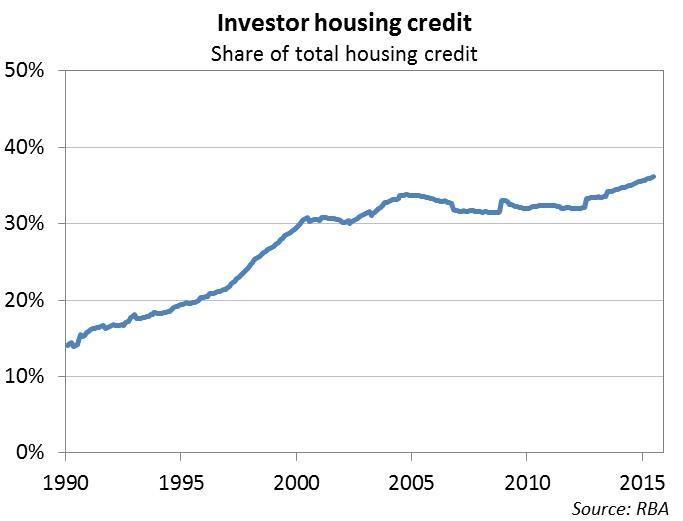

Turning to the composition of loan portfolios, a notable change has been the well-publicised growth in lending to investors. In terms of the outstanding stock of housing lending, investors account for more than one-third; of the current flow of approvals, investors now account for more than 40 per cent. For comparison, in the mid-1990’s both those proportions were around half today’s levels.

A key question is: does this compositional shift change portfolio risk profiles? Australian data suggests that there has been little difference in the propensity of investor loans to become impaired, vis-à-vis those to owner-occupiers. However, caution is needed given the lack of any period of severe household stress over the past two decades: evidence from other countries suggests we should be wary of extrapolating the current Australian experience into more stressful scenarios.

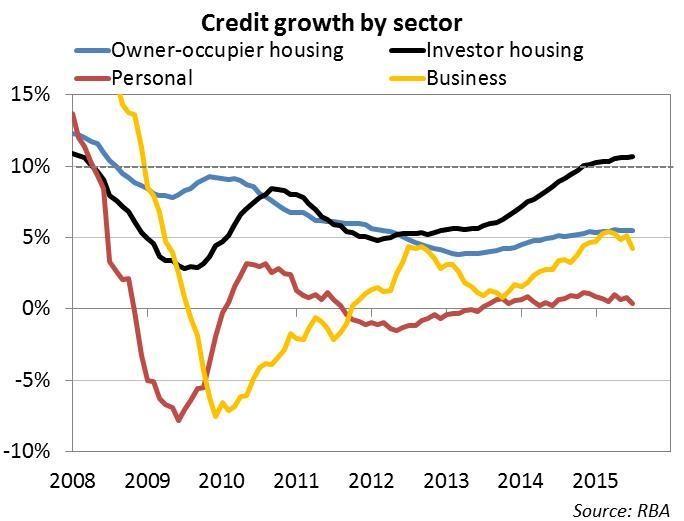

Of course, it is not just the nature of the borrower, but also the growth in lending, that acts as a warning sign for supervisors. When we wrote to ADIs in December 2014, we flagged a benchmark for investor lending growth of 10 per cent, or higher, as a sign of increased risk. We highlighted investor lending because it was an area of accelerating credit growth and strong competition: a combination in which the temptation to compete and protect market share could drive a weakening of credit standards. By moderating growth aspirations, we are reducing the tendency for ADIs to whittle away lending standards in the name of ‘matching our competitors’ – when it comes to lower standards, it’s always the other guy’s fault.

Where they intend to moderate their growth, individual lenders have taken their own commercial decisions as to whether to use price or non-price measures (or both). In discussions with APRA earlier this year, some lenders laid out plans that mentioned the reduction or removal of pricing discounts and incentives for new borrowers as one of a menu of options for tempering growth, in addition to selective tightening of lending criteria. This was consistent with our objective of targeting the standards for, and volume of, new lending. However, a number of lenders have subsequently decided to reprice their existing investor portfolios. Repricing existing loans appears to reflect a preference, by the largest lenders, for price-based measures over non-price measures in the face of strong underlying market demand and limited differential pricing capability, but may well have limited impact on loan growth given the tendency for competitors to match pricing changes.

The growth in investor lending remains marginally above the 10 per cent benchmark, and may well be so for the next few months. However, there has been a moderation in the previous strong upward trajectory, and the large lenders have all indicated their intention to work below this benchmark. If it continues to grow at around 10 per cent, investor lending will still be the fastest growing of the major classes of credit for the foreseeable future, and will be growing at, in broad terms, around twice the rate of nominal GDP. A moderation in lending growth as currently envisaged should therefore not be seen as unduly restrictive: it is not placing a foot on the credit brake, but rather easing off the accelerator.

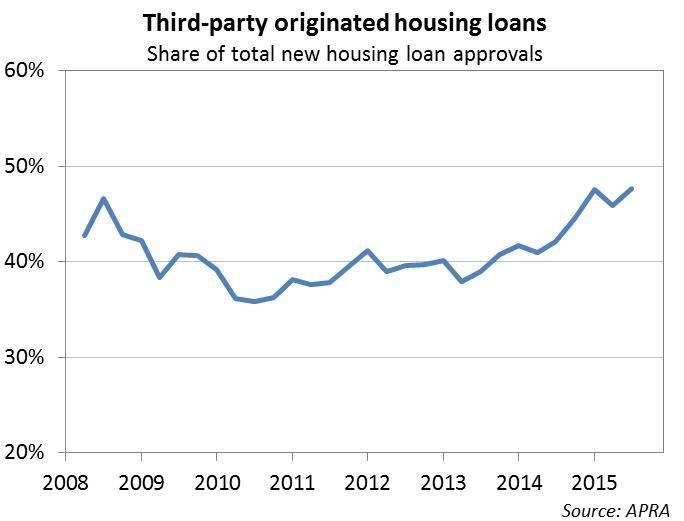

Another feature of the home lending market has been the increasing use of third-party distribution channels. There are potentially significant advantages from such an approach: for example, allowing smaller lenders or new entrants to compete more readily against the established branch networks of the bigger players. On the other hand, third-party-originated loans tend to have a materially higher default rate compared to loans originated through proprietary channels. This does not mean third-party channels have lower underwriting standards, but simply that the new business that flows through these channels appears to be of higher risk, and must be managed with appropriate care.

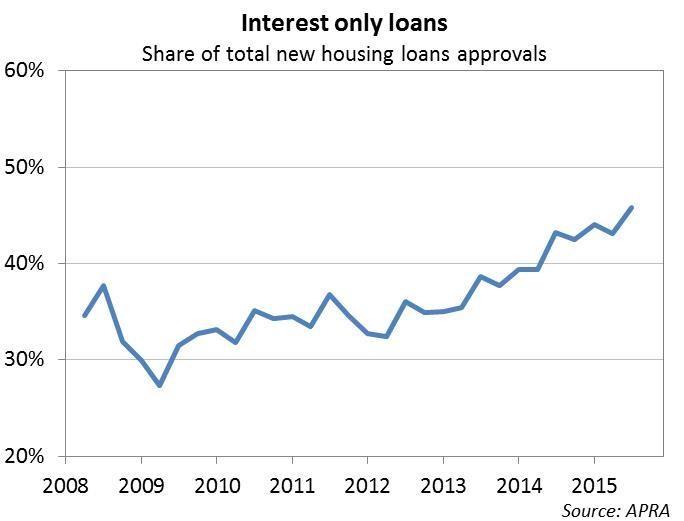

Interest-only lending has grown in its share of new lending. This is not just because investors – who typically make greater use of interest-only loans – are a larger share of lending; investors have been increasing their use of interest-only lending. So have owner-occupiers. There are many reasons offered for why this might be.[5]

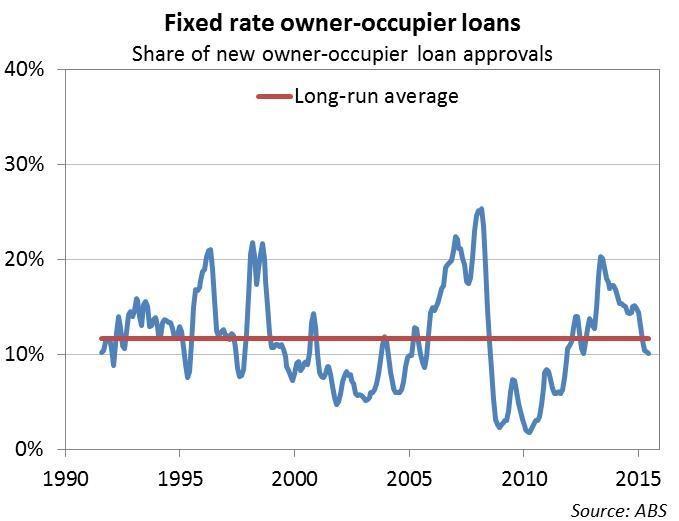

Australians have, thus far, not been taking advantage of record low interest rates to fix the rates on their borrowings. Obviously the sensitivity of borrowers to any increase in interest rates in the future will be a function of the extent to which they have maintained variable rate loans. At least thus far, there is little evidence that this sensitivity is being reduced.

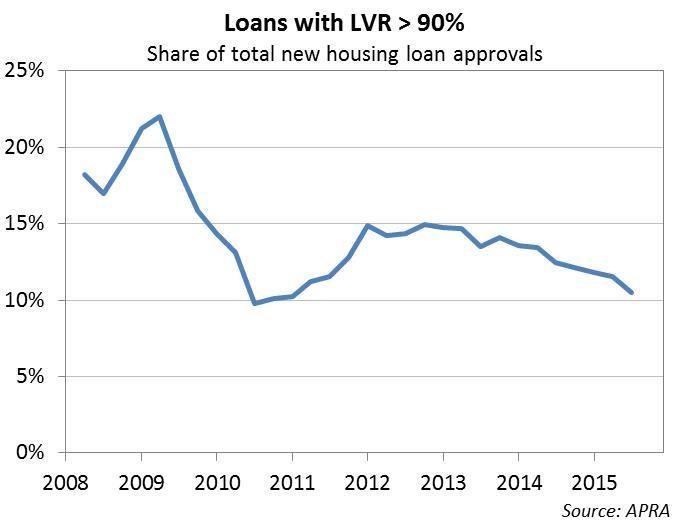

Finally, high loan-to-value (LVR) lending – the focus of a number of macroprudential measures in other countries – does not appear to be a cause for increasing concern in Australia at present. Indeed, the proportion of lending at LVRs above 90 per cent has roughly halved in the post-crisis period (although probably still remains high by international standards, as does the extent of high loan-to-income lending). This declining trend in high LVR lending has been evident most obviously in the case of owner-occupiers, but also applies to investors as well. All else being equal, lower LVR lending is reducing portfolio risk, by providing lenders with greater protection in the event of borrower default.

Housing lending standards

The final layer of analysis has been our detailed review of lending standards at individual lenders. We published some conclusions from this in May.[6]

- generous interpretations of the stability and reliability of borrowers’ incomes;

- borrowers assumed to have very meagre living expenses; and/or

- a reliance on interest rates not rising very much, or (more puzzlingly) rising on new debts but not existing ones.

ASIC’s recently announced review of interest-only home lending made similar findings.[7]

The industry has responded with improved practices in the past few months. For example, it is now commonplace for lenders to apply a haircut to unstable sources of income, and to assume a minimum interest rate of around 7.25 per cent – well above rates currently being paid – when assessing a borrower’s ability to service a loan. These steps should give greater comfort about the quality of new business now being written.

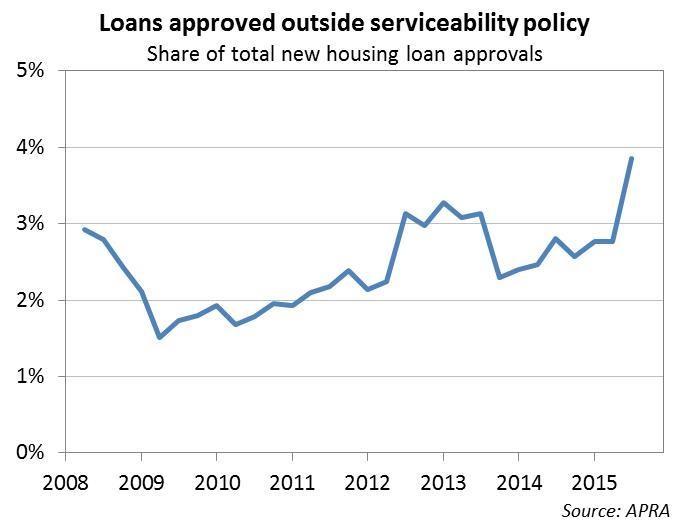

However, a close eye will need to kept on policy overrides – in other words, the extent to which lenders approve loans outside their standard policy parameters. There are some definitional issues that mean care is needed with this data, but the rising trend for loans to be approved outside policy needs to be watched: as lenders strengthen their lending policies, it’s important to make sure this good intent isn’t being undone by an increasing number of policy exceptions.

Is more action needed?

Before I wrap up, I’d like to comment on the potential for further action by APRA, including targeted measures that, it has been suggested, we should employ to specifically respond to rising housing prices in Sydney and Melbourne. In response, I would make three points:

- first, our mandate is to preserve the resilience of the banking system, not to influence prices in particular regions;

- second, the broader environmental factors I outlined at the start of my remarks – high housing prices, high debt levels, low interest rates and subdued income growth – are not present only in our two largest cities; and

- third, sound lending standards – prudently estimating borrower income and expenses, and not assuming interest rates will stay low forever – are just as important (and maybe even more so) in an environment where price growth is subdued as they are in markets where prices are rising quickly.

That is not to say that geographic measures would never be contemplated. Parallels are often drawn with New Zealand, where specific measures have been directed at the rapid price appreciation in Auckland. In comparing the respective actions on both sides of the ditch, it’s important to note the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) initiated measures for Auckland only after first instituting a range of measures that applied New Zealand-wide. In other words, more targeted measures built on, rather than substituted for, measures to reduce financial stability risks nationally.

Given many changes to lenders’ policies, practices and pricing are still relatively recent, it is too early to say whether further action might be needed to preserve the resilience of the banking system. We remain open to taking additional steps if needed, but from my perspective the best outcome will be if lenders themselves maintain a healthy dose of common sense in their lending practices, and reduce the need for APRA to do more.

Concluding remarks

Many of the observations I have made today have been offered in the time-honoured tradition of an economist: ‘on the one hand, and on the other’. But I have essentially made three simple points:

- lending for housing is a large and important part of the banking system;

- the environment in which housing lenders operate is one of heightened risk; and

- there is reason to conclude that housing portfolio risk profiles might have increased, and underwriting standards softened, over time.

Housing lending in Australia has been and remains, thankfully, a long way from the poor practices that led to problems elsewhere in the world. Nevertheless, heightened risk warrants heightened scrutiny. This should be done, first and foremost, by the boards and management of lenders themselves, calibrating their lending policies to the environment of heightened risk.

APRA can’t stop or prevent cycles in prices, or change the broader environment in which lenders lend. Our role is primarily to help reinforce the lending standards of regulated institutions, and moderate overly-ambitious pressures for growth which can lead to imprudent behaviour, to ensure the banking system is resilient to whatever conditions might eventuate in the future.

Footnotes

- ‘Seeking strength in adversity: Lessons from APRA's 2014 stress test on Australia's largest banks’, speech to the AB+F Rand Leaders Lecture Series, Sydney, 7 November 2014. Available at www.apra.gov.au.

- Prudential Practice Guide APG223 Residential Mortgage Lending. Available at www.apra.gov.au.

- ‘Reinforcing Sound Residential Mortgage Lending Practices’, letter to all ADIs, 9 December 2014. Available at www.apra.gov.au.

- And even with recent increases, the ratio of Sydney housing prices to those of the rest of the country, for example, is not necessarily high in historical terms. See, for example, Submission to the Inquiry into Home Ownership, Reserve Bank of Australia, 15 July 2015 – chart 21.

- APRA has been interested in interest-only lending to owner-occupiers, in particular, in case it represents borrowers who resort to interest-only loans when unable to meet serviceability tests on a principal-and-interest basis. Thus far, we have not seen significant instances of this; more commonly, it appears to be borrowers who simply prefer lower immediate repayments, and/or use offset accounts to provide more repayment and redraw flexibility.

- ‘Sound lending standards and adequate capital: preconditions for long-term success’, speech to the COBA CEO & Director Forum, Sydney, 13 May 2015. Available at www.apra.gov.au.

- REP 445 Review of interest-only home loans, Australian Securities and Investments Commission, 20 August 2015. Available at www.asic.gov.au.

The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) is the prudential regulator of the financial services industry. It oversees banks, mutuals, general insurance and reinsurance companies, life insurance, private health insurers, friendly societies, and most members of the superannuation industry. APRA currently supervises institutions holding around $9 trillion in assets for Australian depositors, policyholders and superannuation fund members.