APRA Chair Wayne Byres - Speech to FINSIA 'In conversation with Wayne Byres' event

Some reflections for the future

Thank you to FINSIA for hosting today’s event.

As you know, this will be my last official speech as APRA Chair. After eight years in the role, I thought I would offer a few reflections on some of the themes that have dominated my tenure and draw out some lessons for the future.

Capital

I’ll start with capital, since much of my time has been spent on the build-up of capital, especially in the banking system.

Esteemed British businessman, journalist and essayist Walter Bagehot, writing in 1873, opined that when it came to capital adequacy “the cardinal rule to be observed is that errors of excess are innocuous but errors of defect are destructive. Too much reserve only means a small loss of profit, but too small a reserve may mean ruin.”1 That cardinal rule still holds true today. Indeed, it underpins David Murray’s much more contemporary Financial System Inquiry, which recommended that Australia would be best placed if banks had “unquestionably strong” capital ratios.2

It is not always appreciated that the very institutions we rely on to be the pillars of financial safety and stability are, by virtue of the modern model of fractional reserve banking, very highly leveraged. Banks operate with leverage far in excess of that which would be tolerated for commercial entities. Margins for error are small, and over the past two and a half decades we have seen – through the Asian financial crisis, the global financial crisis and the European debt crisis – the damage that can be done to societies when financial systems are undercapitalised.3

Generating a more resilient banking system has therefore been a prevailing theme during my time in office. From a capital perspective, the Common Equity Tier 1 capital of Australian banks now exceeds a quarter of a trillion dollars. It has increased by $110 billion, or more than 70 per cent, over the past eight years. There is also an additional $126 billion of “bail-inable” debt; an increase of more than $70 billion, or 133 per cent, compared to eight years ago.

Over the same time, banks’ assets have grown by 44 per cent.4 So, some of the extra capital is supporting growth in the banking system itself. But clearly there has been a strengthening in overall resilience. Leverage in the system is lower. The largest Australian banks are capitalised comfortably within the top quartile of their overseas peers, and their credit ratings are high and solid. And notwithstanding higher capital levels, the industry is still producing low double digit returns on equity.

Most importantly, public confidence in the financial system seems robust. During the pandemic, when community confidence was fragile and many worried about access to basic necessities, there wasn’t a concern about access to money. Indeed, the financial system evidenced its strength by supporting the community, acting as a shock absorber rather than an amplifier. As we enter a potentially difficult period ahead, it is a comforting position to be in.

The challenge before us is not to build up even more capital. The primary task is to preserve it for when it is really needed. Having built up that capital strength and resilience, we should not give it up lightly. There are probably three ways that could happen at present.

One is provisioning. Capital is illusory unless balance sheets are fairly marked, and assets are provisioned accordingly. At present, with a deteriorating economic outlook, the release of provisions from bank balance sheets is perplexing and warrants particular scrutiny.

Another is the reliability of capital instruments. Along with shareholders’ funds and retained earnings, regulatory capital contains a range of bail-inable instruments that are intended to provide additional loss absorbing capacity with a high degree of permanency. At present, we see institutions looking to redeem these instruments even though it is uneconomic to do so, in order to meet “investor expectations”. This suggests a misalignment of expectations between regulators and investors that will need to be addressed.

And then from time-to-time, proposals emerge that the strength of the framework should simply be watered down, or that some special interest should get favourable treatment. For example, arguments are put that finance would be cheaper or more abundant if only regulatory requirements were relaxed. Domestically, sometimes certain industries, or borrower cohorts, are said to be deserving of special treatment. In international circles, there is an active debate when it comes to green finance – should regulatory requirements incentivise green lending to aid the necessary transition to a low carbon economy?

Careful thought is needed with these ideas. Quite often, they involve attempts to have the financial system provide (implicit) subsidies.

My own view is that if projects and activities stack up economically, they will attract finance and investment. If they cannot, and there is a desire to subsidise them to ensure they proceed, then that is a matter for governments, not prudential authorities. Trying to use prudential requirements to indirectly produce subsidised finance will not only likely be poorly targeted, but mean that one of two things must happen: either protected liability holders (such as bank depositors) lose some of their protection, or else some other forms of activity need to have higher requirements to offset the subsidy and ensure overall prudential safety is not diminished.

These are legitimate policy questions to debate, but it is important to remember they inevitably involve robbing Peter to pay Paul. There is no free lunch to be had.

Housing

Another constant feature of my time has been that Australian obsession: housing.

Perhaps the most frequent statement I have made in my time as Chair has been that APRA does not have a mandate to control housing prices – so I may as well make it one last time.

APRA’s interest in housing stems from our job to protect bank depositors – who provide the funds that banks lend for housing – and from seeking to promote overall financial system stability. We do that through ensuring bank balance sheets are sound and lending standards are appropriate. Incidentally, that benefits borrowers (by limiting their capacity to overextend themselves) and impacts housing prices (through influencing the demand curve for housing) but both of those are indirect consequences of our core tasks: they are not our goals.

As ever lower interest rates drove the housing cycle upwards, APRA sought to ensure competitive exuberance did not undermine basic credit standards. Much attention has been given to the benchmarks we temporarily introduced some years ago to temper investor lending and interest-only lending. But behind the scenes, against a backdrop of increasing risk, we have been persistently reinforcing lending standards across the board: improving income verification practices, insisting on more than an assumption of poverty line living costs, requiring better assessments of a borrowers’ ability to service not just their mortgage but their aggregate debt levels, and generally increasing the buffer for uncertainty.

Australia now finds itself in an environment we all knew would eventually come: one of rising interest rates and falling house prices. Both are occurring sooner, and at a faster rate, than most people anticipated a year ago. When things shift suddenly and unexpectedly, as they have, not everyone finds it easy to manage. Borrowers with only a small equity buffer and/or high levels of leverage relative to their income will be particularly challenged. Borrowers currently on very low fixed rates face a significant repayment shock in the future.

The existence of some borrowers in difficulty is not a sign of weak lending standards. After all, a bank that does not make a bad loan will be a bank that denies credit to many good customers. Banks will need to work with hardship cases sensibly. But prudential regulation is designed to ensure that downturns can be weathered. In Australia, the banking system is in good shape to weather the adjustment, and – notwithstanding there will be pockets of stress within loan books – there is no sense it will threaten the soundness or stability of the system. The build-up of prudential strength has seen us navigate the past couple of years well and, with careful stewardship, will see the system resilient through the next few as well.

I would also add that it is not all downside from falling housing prices. Australian housing prices are undeniably high, and a sustained lower level of prices would be no bad thing overall. Our decisions as a society to turn an ostensibly abundant resource – land – into something highly valuable, requires the community to take on very high levels of debt to house themselves. First home buyers need more than a decade of diligent saving to put together a deposit, creating a major barrier to entry into the housing market.

As a nation, we fret about housing affordability. The only way to genuinely improve affordability over time is to keep the rate of increase in housing prices below that of our incomes. From a narrow financial stability perspective, lower housing prices facilitating lower debt levels would be no bad thing. From a broader societal perspective, I suspect there would be many more benefits from people having to use less of their income to simply put a roof over their head.

Competition

The discussion on housing provides a neat segue into another recurring theme: competition.

Some of our interventions on housing were criticised because they dampened competition. They did, and deliberately so. We saw competitive pressures playing out in the form of lower credit standards. Preventing that erosion was important in an environment of rising risks: rising house prices, high household debt; subdued income growth and extremely low interest rates. These were conditions in which one might expect a prudent bank to be trimming its sails, not hoisting the spinnaker.

Even so, that does not mean we did not have regard to competition. Given the risks were systemic in nature, we constructed our interventions such that, during this period, the tools chosen and the way they were imposed impacted most heavily on the largest lenders. As a result, small lenders, who often chaffed at the perceived competitive constraints, were nevertheless able to increase their market share during this period.5

We have also dealt with a long-standing debate about the impact on competition from differences in housing loan risk weights within the capital framework.

Like beauty, the view on housing risk weights is usually in the eye of the beholder. They are viewed as too low (driving the flow of credit into housing over other activities), too high (unnecessarily raising the cost of housing finance), and too differentiated (giving larger banks with internal models an advantage over smaller banks using the standardised approach).

In the past few years, we have achieved three key outcomes with risk weights:

- there is more capital allocated to housing loan portfolios, reflecting the heavy concentration of mortgages on the balance sheet of the banking system;

- we have embedded the differential pricing between owner-occupied and investor lending, and between amortising and interest-only lending, by setting differential capital requirements; and

- the gap between risk weights from internal models and the APRA-prescribed standardised approach has been substantially narrowed.

On this latter point, the complexity of the risk weighting framework sometimes masks the reality. Headline risk weights are not directly comparable because of differing requirements in the way capital adequacy is calculated.6 We therefore need to assess differences on a more realistic, like-for-like basis. Broadly speaking, prior to the Financial System Inquiry, the difference was reasonably wide: an average mortgage risk weight of 39 per cent for standardised banks versus an average of 18 per cent for banks using models. Today, on a like-for-like basis it is 38 per cent to 31 per cent, and the gap will narrow fractionally further under the new capital regime coming into force from 2023.7,8

We still hear complaints from bankers that we have not addressed this issue. I’d suggest they are not letting the facts get in the way of a good story.

Stepping back, however, it is true that a prudential supervisor will lean towards promoting stability over promoting competition. After all, that is how Parliament has established our mandate. But that does not mean we do not think about competition. Our approach has always been one of recognising that competition and financial stability can, with the right settings, be mutually reinforcing.9

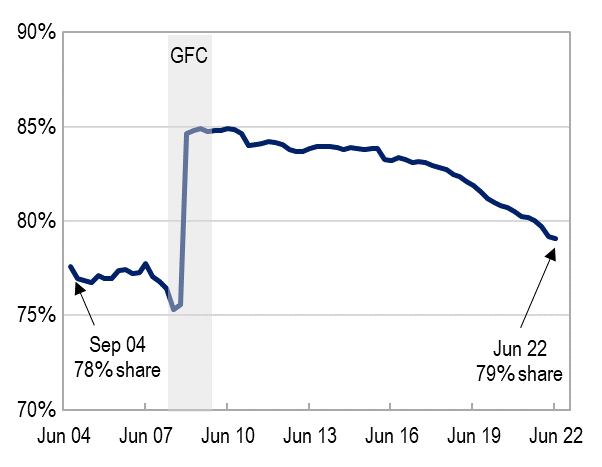

Moreover, history also tells us that periods of instability are often bad for competition. In good times, new competitors can attain the confidence and capital needed to attack the market share of the major incumbents. In downturns, through capital scarcity, flight to quality and acquisitions, that market share is reacquired (and often more) by the largest institutions. One only has to look at the market share of the major banks in housing loans to see the story.10

Major banks' share of total ADI housing loans

The idea that the pursuit of stability must come at the cost of competition is a furphy.

Superannuation

Nowhere has there been more change in my time as Chair than superannuation.

When I started as Chair, the Stronger Super reforms – including a much-needed and long-awaited prudential standards-making power for APRA – were just settling in. Stronger Super brought MySuper into being and was followed by reforms such as the Protecting Your Super and Your Future, Your Super packages. And of course, there were important inquiries, such as the Productivity Commission and the Hayne Royal Commission.

Much of that scrutiny and change has been necessary to produce a better superannuation system for Australians. By and large it has. There is more to do, but the reforms have undoubtedly driven the industry in the right direction.

If I reflect on what has been the most important and impactful of all the changes, I think it has been the increased transparency that has been forced upon the industry.

During the Royal Commission, Counsel Assisting Michael Hodge KC posed the question: “What happens when we leave these trustees alone in the dark with our money?” It was a very good question. Given the weak accountability that most superannuation trustees are subject to by virtue of their ownership structure and limited member engagement, corporate interest and self-interest can sometimes outweigh member interest. Transparency has been key to increasing the discipline on trustees to ensure they are always managing members’ money in their (i.e. members’) best interests.

In saying that, I am not suggesting every single thing about a fund’s operations must become public. Clearly, there will be commercially sensitive information that could disadvantage a fund’s members were it to be disclosed. And pumping out reams of raw data is not going to be helpful. Information must be disclosed in a manner that is digestible and informative if it is to be useful.

However, we have made significant strides: first with APRA’s heatmaps, then with the addition of the statutory performance test, and with more to come from APRA’s improved data collections. This transparency has been the single most powerful force in driving better member outcomes, shining the spotlight on underperformance and giving trustees who are not delivering for their members no place to hide.

That is important because, given a blank sheet of paper, you would not give the superannuation industry the shape it has today. In an industry where size matters, there is still a long tail of smaller funds whose longevity is challenged.11 This generates inefficiencies in the system, the cost of which is ultimately borne by members.

In making this point, it is not simply a case of “big is good, small is bad”. Our heatmaps identify large funds that must do better, and small funds that are delivering well for their members. But, overall, the evidence is clear that size helps deliver better member outcomes. Trustees that cannot compete on that basis need to think very hard about how (and whether) they can deliver in their members’ best financial interests, now and into the future. The spotlight on them will only get brighter and more intense.

Community expectations and responsibilities

Finally, to APRA itself. Most of APRA’s work goes unseen and unremarked. That is as it should be. A good prudential supervisor is like the referee of a football match: she or he will feel happy if the after-match reporting praises the skill of the players and flow of the game, with the quality of officiating largely unnoticed.

APRA is set up to primarily work behind the scenes – identifying and addressing issues before they become problems, rather than doing the clean-up afterwards. To start with, we operate under strict confidentiality provisions. Added to that, most of APRA’s regulations come in the form of prudential standards – and the statutory sanction for breaching one is simply to be given a direction by APRA to comply. We have in recent times tried to give greater transparency to what we do, including where we are taking some form of enforcement-related action. But because of the nature of both our mandate and our toolkit, we are not an agency that, for example, will often operate through the Courts.

Occasionally, though, circumstances arise when we can show our wares. The most notable of these in my time was the CBA Prudential Inquiry. Against the backdrop of increasing reputational damage to Australia’s largest financial institution, we set out to not only get to the bottom of the issues once and for all but also provide a roadmap for redemption. We did so in an innovative way and largely without recourse to legal powers.12 The final report, given the breadth of the issues it covered, was fast to complete, high quality in its analysis and impactful in its outcomes – with the impact felt far beyond the bank itself.

In recent times, the message to regulators has generally been to be tougher. Powers and sanctions have been strengthened by Parliament, and regulators are expected to use them. APRA has heard that message. But we also seek to be “constructively tough”. The Prudential Inquiry was an example of our approach: it certainly pulled no punches, but its most important contribution was a constructive set of recommendations that provided a clear path to improvement, something the bank has acknowledged and embraced to its benefit.

More broadly, the community expects high standards from its regulators. That is fine – every regulator I know tries very hard to live up to the community’s expectations. However, it is also important that the community accepts that regulators, no matter how good they are, are not omnipresent or omnipotent.

Nor are regulators charged with guaranteeing that bad things will not happen. In APRA’s case, there is no mandate from the Parliament to prevent failure at all costs. In fact, the Statement of Expectations we have been given has always acknowledged – very rightly, in my view – that APRA should not pursue a zero-failure regime. This is despite the fact the disorderly failure of a financial institution, were it to happen, would be extremely disruptive and costly. Other regulators have similar limitations as to what they can promise.

Indeed, it is almost inevitable that every so often things will go wrong in the financial system, and participants will suffer losses. This should not automatically be assumed to be a regulatory failure. It may well simply be a natural – if at times uncomfortable – product of having a competitive, efficient and innovative financial sector that is not completely drowned in red tape.

Sometimes, when such things happen, governments feel obliged to provide compensation to those who suffered loss. That is a perfectly legitimate decision for a government to make. But it is important that a degree of caveat emptor remains in the design of the financial system. I have made this point before – perhaps unwisely, during the middle of the Royal Commission – but I repeat it because it is important.

No one wants a financial system that resembles the Wild West. Laws and regulators protect the community by reducing the probability of bad outcomes and limiting the impact when they occur. But there are limits to what can be achieved. Consumers of financial services still need to take a degree of responsibility for their decisions. Indeed, there are benefits to stability, competition and efficiency when they do.

In recent years, I suspect the expectation in the minds of many in the community (and in financial markets, for that matter) that governments will backstop bad outcomes has only grown. Not only is it not always possible, but it risks creating a moral hazard in which the downside from risk-taking is underestimated at best, and ignored at worst. Problems of under-insurance, in all its forms, will only grow. And if the providers of financial services are continually deemed responsible for poor consumer choices, the provision of financial services will inevitably be restrained.

All that might sound like a slightly odd message coming from someone who is tasked with protecting the community. But in the long run if we do not get the balance right it will deliver an inefficient financial system, and a net loss to the community as a whole.

Conclusion

I have spoken today about themes that have been a constant during my time in office. Each will undoubtedly remain important for my successor, albeit jostling for attention with newer issues which, during my time as Chair, have now become mainstream: risk culture and incentives; digital finance and crypto assets; cyber security; and climate risks, to name a few. Time prevents me from speaking on each of those issues today, but needless to say APRA has no small agenda before it.

I have been fortunate to be Chair of APRA through some fascinating times. I have had tremendous support from my regulatory colleagues, both inside and outside APRA, and from Governments of both political persuasions who have understood the importance of a strong prudential supervisor. I am very grateful for that.

Notwithstanding there are always misgivings that some part or other is not quite working as well as we would like, we have a good financial system in Australia. Having had the chance to look around the world at circumstances elsewhere, I rarely find myself thinking that I would swap what we have for others.

I have been asked a couple of times about what I think my legacy might be. I leave that for others to judge. What I can say, though, is that APRA’s job is first and foremost to deliver a safe and stable financial system – fail at that, and nothing else matters. Thankfully, we have delivered on our core mandate, despite some pretty interesting ups and downs.

And as I look at APRA as an organisation, I am very pleased with the depth and breadth of talent within the organisation, and with the strong commitment its people have to its purpose – protecting the financial wellbeing of the Australian community.

That combination of talent and commitment means I leave very confident that APRA will continue to successfully deliver on its mandate well into the future.

Footnotes

1Bagehot, Walter (1873). Lombard Street: A Description of the Money Market, p323.

2Bagehot (p322) even had his own rationale for ‘unquestionably strong’: “At every moment there is a certain minimum which I will call the 'apprehension minimum,' below which the reserve cannot fall without great risk of diffused fear …. if any grave failure or bad event happens at such moments, the public fancy seizes on it, there is a general run, and credit is suspended. The Bank reserve then never ought to be diminished below the 'apprehension point.' And this is as much as to say, that it never ought very closely to approach that point; since, if it gets very near, some accident may easily bring it down to that point and cause the evil that is feared.”

3Australian policy settings need to also be considered against the backdrop that, unlike many overseas jurisdictions, there is no pre-funded deposit or policyholder insurance scheme or resolution fund in Australia that can be used in the resolution of a failing financial institution to protect taxpayers.

4For comparison purposes, assets of foreign bank branches are excluded given they do not have capital requirements.

5See Information paper - Assessment of APRA's measures on residential mortgage risk.

6For example, IRB banks need to hold capital for ‘expected loss’ (or more accurately, take a capital deduction for any amount not covered by provisions); the prescribed credit conversion factor for mortgages for IRB banks is 100 per cent, versus only 40 per cent for standardised banks; and IRB banks are required to hold an additional ‘IRB capital buffer’ that effectively increases IRB risk weights by a factor of around 1.15x.

7Even on this more like-for-like approach, the comparison does not take account of additional requirements that apply to IRB banks, such as interest rate risk in the banking book. This makes the effective gap even smaller.

8It is sometimes suggested that the average differential masks more problematic differentials for different types of loans, especially safer, low LVR loans. For loans with LVRs below 60 per cent, the pre-FSI differential was 35 per cent (standardised) versus 14 per cent (modelled). Currently, the differential is 35 per cent versus 25 per cent. From 2023 when a more risk-based approach is introduced, that differential will be 25 per cent versus 18 per cent.

9APRA’s approach to balancing its objectives is set out in Information Paper – APRA’s objectives. In a practical sense, there are a number of steps APRA has taken in recent years with a competition perspective firmly in mind. These broadly fall into four categories: (i) facilitative measures that promote more active competition by, for example, providing for the issuance of mutual capital instruments, and making the licensing regime easier to navigate for new entrants; (ii) graduated approaches to regulation that avoid undue costs on smaller competitors, (iii) simplification efforts that reduce the burden on smaller entities by easing regulatory and reporting requirements; and (iv) ensuring supervisory intensity is proportionate and applied where it is most needed from a systemic risk perspective when macroprudential and thematic issues are pursued.

10Much of the commentary on this period focuses on the acquisition of St George and BankWest by two major banks. But equally important was the higher funding costs experienced by less well rated competitors (banks and non-banks alike), and the effective closure of securitisation markets for a period. This took some time to unwind. As a result, it was more than five years after the GFC before the majors’ market share in housing lending began its downward trend again in any material way. It is only now back to a level it was almost 20 years ago.

11Of the 141 APRA-regulated funds, 104 have less than $10 billion in funds under management, and 78 have less than $2 billion (that is, less than 1 per cent of the size of the very largest funds). Collectively, those 104 small funds – 74 per cent by number – manage only 6.6 per cent of assets. In contrast, 16 large funds have more than $50 billion in funds under management each, collectively accounting for more than 70 per cent of assets.

12It must also be acknowledged that the ability to undertake the Prudential Inquiry in the way it was done was predicated on the commitment to cooperation provided by the Chair and CEO of the bank.

Media enquiries

Contact APRA Media Unit, on +61 2 9210 3636

All other enquiries

For more information contact APRA on 1300 558 849.

The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) is the prudential regulator of the financial services industry. It oversees banks, mutuals, general insurance and reinsurance companies, life insurance, private health insurers, friendly societies, and most members of the superannuation industry. APRA currently supervises institutions holding around $9 trillion in assets for Australian depositors, policyholders and superannuation fund members.