APRA Chair Wayne Byres - Speech to the 2021 AFR Banking Summit

Banking on an unpredictable future

Good morning.

I’m pleased not only to be with you today, but to be with so many of you in person, which is a nice change from much of the past 12 months.

As is fitting for a banking summit, my goal this morning is to give you a picture of our priorities in banking for the year ahead. But if recent events have taught us anything, it’s that there is no guarantee our agenda will unfold precisely as we intend.

That is no more evident than in what we have all experienced in the past 12 months. Early forecasts of the economic impact of COVID-19 were truly dire. They prompted unprecedented levels of fiscal and monetary support, which not only avoided the terrible outcomes that were forecast, but now sees Australia enjoying a strong recovery that seemed quite fanciful not that long ago.

So to borrow a phrase, it is difficult to make forecasts, especially about the future. Yet preparing for an uncertain future lies at the heart of a resilient financial sector.

We know shocks will come. We just don’t know when or where the next one will come from: geo-politics, trade tensions, natural catastrophes, health crises, cyber-attacks, fraud or recklessness, just to name a few. From whatever direction it emerges, however, it’s essential for the community’s ongoing prosperity that Australia’s banks, insurers and superannuation funds have the skills, experience and financial wherewithal to respond effectively and, in the very rare cases where they can’t, that the official sector has plans to deal with that too.

If you have attended these events before, you will have heard me talk about the importance of resilience. When it comes to the banking sector, our plan to sustain and enhance its resilience centres on what we call internally “the 5 Cs”: capital, credit, cash, continuity and contingency.

Capital

I have spoken at half a dozen of these summits over the years, and capital has been a regular topic. It’s the cornerstone of a bank’s financial resilience. For that reason, capital management was a key focus for APRA in the early days of the pandemic.

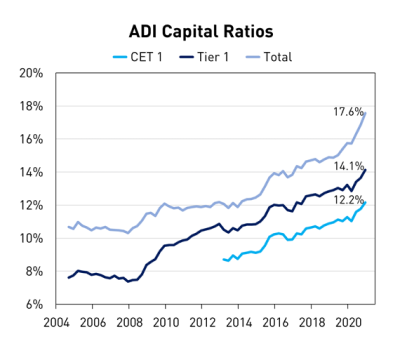

The banking system entered the crisis in a historically strong capital position. Due to a combination of capital raisings, dividend restraint and subdued asset growth, that position has only strengthened since then. The CET1 capital ratio of the banking system finished 2020 at 12.2 per cent, a historic high. With an additional 500 plus basis points of other loss absorbing capacity, the core financial resilience of the banking system is as strong as it has been in recent memory.

Nonetheless, capital reform remains high on APRA’s agenda for 2021. I described this work as “unfinished business” at last November’s AFR Summit, and we subsequently published a discussion paper in December outlining a set of wide-ranging, but hopefully close to final, changes to the capital framework.

It’s important to reiterate that these reforms do not ask the banking system to build more capital – the chart above shows that’s already been done. Nonetheless, the proposed reforms help build a banking system that is better equipped to respond to adversity. Once fully implemented, the capital framework will operate with:

- more flexibility, with a greater proportion of capital held as buffers that can be drawn down in periods of stress and reflated afterwards;

- greater risk sensitivity, with more differentiated risk weights in some important areas such as housing and SME lending; and

- enhanced transparency to ensure capital strength can be more easily understood and compared, both domestically and internationally.

The changes should also support competition in the system between banks using modelled and those using non-modelled approaches, including by providing a simpler framework for banks with simple business models.

As for timing, our goal is pretty simple: finish the consultation this year, and give the industry a 12-month implementation runway to be ready by 1 January 2023. Once the proposed changes are implemented, we will have a stronger capital framework that will help to future-proof the system from the next crisis, from wherever it may come.

Credit

The second C is credit.

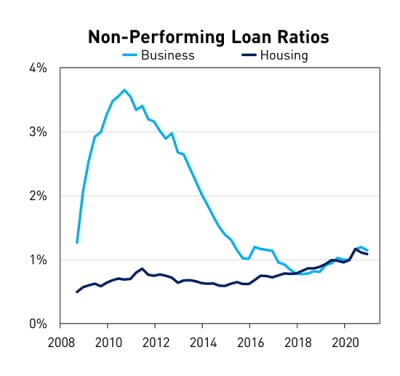

COVID-19 was inevitably going to produce an increase in impaired assets, but so far this has been nothing like the experience of the 2008/09 global financial crisis (GFC). Of course, non performing loans have been suppressed by temporary Government support and a major program of loan deferrals, both of which are coming to an end. But the signs are good that any further increase in impaired assets will be quite manageable – rather than a major surge – given the improvement in underlying economic conditions.1 And banks have built up their provisions well in advance of this.

However, non-performing loan ratios tend to be a lagging indicator of economic health. Aside from the immediate economic shock from COVID-19, it is also producing longer term structural changes to regions and industries There are changes to the way we shop, work, travel and entertain ourselves and, for some, even where we live. All of this, and its impact on credit quality, will take time to play out.

In an environment of heightened risk, it is important that banks do not become too conservative in their lending. At the core of our regulatory responses to COVID-19 – for example, deferrals, the use of capital buffers, and restraining dividends – was the need to make sure credit kept flowing. We did not need risk aversion amongst lenders exacerbating an already troublesome situation.

At the same time, we don’t want to see credit standards, particularly in the area of housing lending, weakened. The goal is to sustain a balance that allows good quality customers to obtain a sensible amount of credit in a timely manner.

With that in mind, let me make a couple of comments on the way we are currently looking at housing markets, given there has been a lot of forecasting recently that APRA might take action in response to rapidly rising prices. Indeed, in recent weeks, the debate seems to have shifted from whether APRA will do something, to when we will do it.

First, let me remind you about my earlier comment on the perils of forecasting!

Second, let me remind you that we have no mandate to target the level of housing prices, or act to improve housing affordability. For us, housing prices are a risk factor, not a goal.

Third, our actions are driven by considerations of financial stability and risk taking. So, what do key metrics tell us?

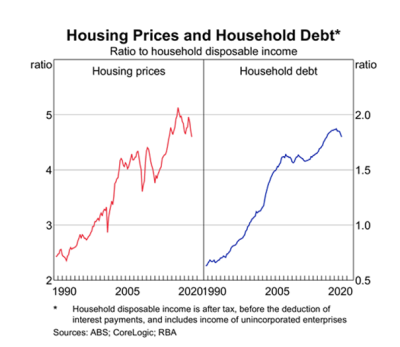

Household debt levels are undeniably high, but have declined relative to income recently. Serviceability of that debt is also being supported by historically low interest rates. On the radar, however, are signs that housing credit growth is picking up, and likely to outpace income growth for the foreseeable future.

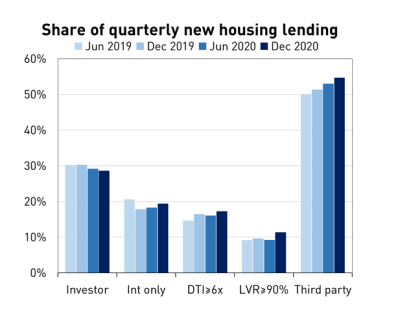

At an aggregate level, lending statistics do not show major signs of a return to higher risk lending. The shares of investor lending and interest only lending – areas where we previously intervened – are below where they were 18 months ago, and well down on the previous cycle. On the other hand, the shares of high LVR lending, high DTI lending and broker-originated lending are increasing (albeit not at a particularly rapid rate, and at least some of this is simply a product of the relatively high share of first home buyers entering the market).

So it is a nuanced picture. There does not seem cause for immediate alarm. Nor, though, for complacency.

We are obviously watching risk-taking by the banking sector closely, along with our colleagues on the Council of Financial Regulators (CFR). We are alert to signs that very low interest rates and rising housing prices create a dynamic in which households seek to take on even higher debt levels, and that banks searching for credit growth seek to accommodate that demand through greater risk taking. That could be in the form of looser lending standards, relaxing portfolio limits, or simply not adjusting to market developments. At an aggregate level that is a scenario that’s not evident yet, but the aggregates can hide a lot so we are digging into this more deeply, as you would expect.

We expect that bank boards, management teams and credit risk officers are interrogating these trends closely too. They should certainly be expecting questions from us on it!

Should risks materialise we have a range of tools we could employ, ranging from interventions similar to that in 2015 and 2017, to the countercyclical capital buffer and (if appropriate) the new non-ADI lending rules. The exact tool(s) we choose will depend on the environment we face, and we are giving careful thought to which tools might work best in different scenarios. But it is obviously not wise to precommit to any course of action until we have a clearer view of the problem we are seeking to solve.

Cash

Our third C is cash – or, without the same alliterative quality, liquidity and funding.

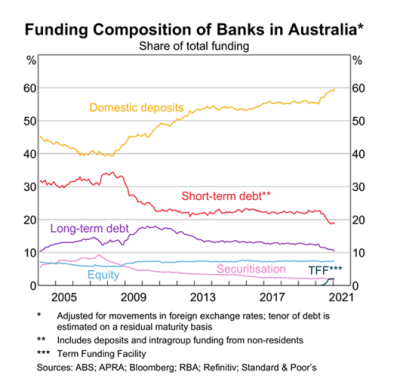

Banks can only sustain a resilient flow of credit if they can be confident they have resilient sources of funding. In the initial stages of the pandemic, the RBA made sure of that. The Term Funding Facility (TFF) and expanded open market operations ensured banks could confidently lend without fear that their funding might dry up during a period of financial stress.

But the TFF is still just one part of the story; there has been a broader shift in funding as well. As it turned out, the banking system has been awash with liquidity. In particular, the Government’s economic support measures created significant inflows into the banking system: deposits grew by more than 6 per cent in the first six months of 2020, pushing the share of funding provided by deposits to its highest level in many decades. With lending growth subdued (in the same period deposits grew 6 per cent, loans grew 1 per cent), liquidity ratios were very healthy, and the reliance on short-term wholesale funding fell notably.

We now expect to see something of an unwind. As government support measures wind down, deposit growth has begun to slow. Banks have started to return to wholesale funding markets, and this need will inevitably increase when banks have to begin repaying the TFF in two years’ time. Of course, we are also hoping lending growth – particularly and preferably to the corporate sector – picks up, and all this is happening at a time when the Committed Liquidity Facility is reducing in size.

None of this is of immediate concern, but it will continue to have our attention because the complexity of the moving parts does require ongoing vigilance to make sure that it can all be managed in an orderly manner.

Continuity

The fourth C in my list is continuity – another way of referring to operational resilience.

Weaknesses in operational resilience can have both financial and non-financial impacts, and in the extreme can jeopardise a bank’s ongoing viability. Although Australians saw no material disruptions to financial services through the pandemic, there were times – particularly as countries around the world imposed widespread lockdowns which directly affected outsourced service providers – that that was only due to a lot of scrambling behind the scenes, and the relaxing of controls not previously contemplated. There are plenty of lessons to capture for the future.

We are therefore conducting a comprehensive review of our prudential requirements for operational resilience. This review will consider the introduction of a new prudential standard specifically focused on operational risk management, revisions to the existing Prudential Standards for Outsourcing (CPS 231) and Business Continuity Management (CPS 232), and additional guidance for entities to encourage better practice. We will also be looking at our pandemic planning guidance (CPG 233). While it more than proved its worth in the face of COVID-19, no doubt there are further improvements possible. Together, this package will form part of a suite of standards covering operational resilience.

The suite also includes our relatively new standard on Information Security (CPS 234). We are intensifying our focus on cyber resilience, working very closely with other arms of the Australian government. As we have said on a number of occasions, no APRA-regulated bank, insurer or superannuation fund has suffered a material cyber breach yet, but it’s only a matter of time until an incident occurs. Recent moves by state-sponsored hackers and criminals to exploit a vulnerability in Microsoft Exchange are a timely reminder that cyber threats continue to grow, requiring a continuous cycle of investment in improved practices.

One notable aspect of our cyber supervision strategy is a focus on third party providers, not just regulated entities themselves. The recent SolarWinds and Accellion breaches are pertinent reminders of the way a cyber breach can have a cascading impact through the wider system. That concern also applies to operational resilience more broadly.

During COVID-19, it was often the failure of third-party providers to meet agreed service levels, rather than failures in banks’ own operations, that created operational and processing problems. COVID-19 also highlighted difficulties in substituting or switching to alternate service providers in a timely manner to maintain continuity of operations.

With an increasingly complex web of third-party relationships supporting the financial system, a key goal of ours therefore has to be to obtain better assurance as to the resilience of not just banks, but the broader ecosystem in which they operate.

Contingency

Our fifth C is contingency.

COVID-19 has been a timely reminder that financial institutions must be ready for all manner of contingencies, including severe shocks from unexpected directions. It is also a reminder that the official sector needs to be ready should banks’ best laid plans be insufficient for the scale of the problems.

From a prudential perspective, contingency planning starts with banks developing their own plans to guide their recovery from a severe financial stress event. Institutions have come a long way over the last few years in their recovery planning, although not all plans are yet as credible and ready to use as we would like.

Even with well-developed plans, however, there is no guarantee they will be sufficient. So contingency planning for APRA also includes preparation for the possibility that a bank’s recovery actions are unsuccessful, and we have to engineer an orderly exit from the industry. In regulatory jargon, this is termed resolution planning, and the effective resolution of problem banks is vital to ensuring their failure produces minimal disruption to critical services, and doesn’t threaten financial system stability. Looking back to the GFC, there were numerous instances around the world where the absence of adequate resolution plans rapidly worsened an already panicked environment.

On the other hand, the recent small case of Xinja is a handy illustration of successful resolution. When it became clear the bank’s trajectory was unsustainable, APRA worked closely with the Xinja board to resolve the bank by returning deposits in full and in a timely and orderly manner, ensuring no depositor lost money and there was no contagion to other parts of the system. From my perspective, it was a successful failure.

In last year’s budget, the Government approved a temporary increase in APRA’s resources to implement a stronger recovery and resolution prudential framework. The new framework will formalise APRA’s requirements on recovery planning and set out obligations on institutions to cooperate with APRA in the development and implementation of resolution plans. We expect to progress the development of the prudential standard in the year ahead, with a view to releasing a draft standard for consultation in late 2021 or early 2022.

A sixth C

There are more Cs I could talk about. Culture and climate come to mind. But these are not just banking issues, so I will leave them for another day.

However, before wrapping up, I’d like to touch on a sixth C … competition.

APRA’s mandate requires us to balance competition alongside our primary prudential objectives.2 Competition is vital to a healthy financial system, and, with the right balance, competition and financial stability can be mutually reinforcing.

Our introduction in 2018 of the Restricted ADI licensing pathway was designed to facilitate competition by making it easier for new entrants to navigate the licensing process. Xinja’s recent exit, as well as 86400’s decision to seek to merge with National Australia Bank, prompted some to predict the demise of the neobank model. With apologies to Mark Twain, let me suggest their death has been greatly exaggerated.

With the resumption of licensing at the start of this month, we are now considering upwards of a dozen applications from aspiring ADIs. These applications cover both the direct and restricted ADI pathways, and many incorporate innovative technologies and business models. Not all will be licensed, but there is no lack of interest.

We have recently revised our licensing framework, to place a greater emphasis on longer-term sustainability rather than the short-term goal of obtaining a licence. Our objective is not to make obtaining a banking licence harder. Rather, we want to improve the prospects of those who enter the market: after all, there is little competitive benefit if new entrants quickly fall by the wayside. Adding explicit requirements such as the need to have an income-generating product are hardly onerous expectations. But hopefully they will help sharpen up prospective entrants’ plans, and give greater comfort to everyone involved that a new entrant can add to the competitive dynamics of the industry.

Concluding remarks

The Australian banking system withstood 2020 very well, both from a financial and operational perspective. We – the industry, its regulators, the government and the Australian public – should all be pleased with that.

From APRA’s perspective, though, caution (another C!) remains the watchword. The economic recovery that is both welcome and well underway will nevertheless be uneven, and there is still some way to go. Globally, the health and economic picture is mixed. New shocks could emerge at any time. Continually focusing on bolstering resilience to future events remains a sound investment in our view.

After all, we might not be able to forecast the future, but it’s always wise to be preparing for it.

Footnotes

1 For example, of the peak volume of loan deferrals, roughly 95 per cent are no longer deferred, and of these, about 95 per cent have returned to performing status or been repaid. Even if the residual volume of loan deferrals were all reclassified as non-performing, it would only increase the ratio of non-performing loans to total lending by around 40 basis points.

2 For a fuller explanation of how APRA seeks to balance the various aspects of its mandate, see the Information Paper on ‘APRA’s objectives’ available from APRA’s website.

Media enquiries

Contact APRA Media Unit, on +61 2 9210 3636

All other enquiries

For more information contact APRA on 1300 558 849.

The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) is the prudential regulator of the financial services industry. It oversees banks, mutuals, general insurance and reinsurance companies, life insurance, private health insurers, friendly societies, and most members of the superannuation industry. APRA currently supervises institutions holding around $9 trillion in assets for Australian depositors, policyholders and superannuation fund members.