Speeches

APRA Executive Board Member, Geoff Summerhayes - Speech to the International Insurance Society Global Insurance Forum

Buy now or pay later

Geoff Summerhayes, Executive Board Member - International Insurance Society Global Insurance Forum, Singapore

Good morning, and thank you for the invitation to speak here today in Singapore. As part of the global financial regulatory community, the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) always finds it valuable to attend events such as this to hear from our international peers and stay on top of new developments.

It’s also a chance to keep you abreast of developments in our part of the world, such as Australia’s recent national election. Observers of Australia may be aware that climate change has been an issue of vigorous political and community debate for at least the past 15 years. Demands from one part of the community for clear and firm action to address climate-related risks are met with equally strong opposition from other sectors of the community that view managing climate risks as economically expensive and financially harmful. The debate is also a product of two important dimensions of the problem. First, the risk is global, yet the costs of action may not fall evenly on a national basis. And second, the benefits will accrue in the future, but many of the costs of change must be borne now. For the Australian community, this remains a highly contentious set of issues.

The tension between the environmental necessity of taking decisive action to limit global warming, and the economic impacts of doing so, is not an exclusively Australian phenomenon. We have seen US President Trump’s winding back of efforts to curb emissions, citing the cost implications for the American economy. In France, the Government’s attempt to raise gas prices was met by angry street demonstrations, forcing a back down. More recently, April’s Finnish election was dominated by conflict over climate policy, with a far-right political party gaining significantly from its campaign against the short-term costs of taking action.

This tension is premised on an indisputable truth: the level of economic structural change needed to prepare for the transition to the low-carbon economy cannot be undertaken without a cost. But it’s also true that failing to act carries its own price tag due to such factors as extreme weather, more frequent droughts and higher sea levels.

Conducting an informed debate about this trade-off is hampered by the lack of reliable data on what the costs are, and how they will evolve years or decades ahead. As experts in risk management, the global insurance industry can – and must – play a leadership role in addressing this data deficit. By developing more sophisticated tools and models, and especially through enhanced disclosure of climate-related financial risks, insurers can help business and community leaders make decisions in the best interests of both environmental and economic sustainability.

The physical-transition risk trade-off

APRA first publicly raised this issue in early 2017, warning that some climate risks are distinctly financial in nature, and that many of those risks are foreseeable, material and actionable now. That message has since been publicly endorsed by our two other major financial regulators: the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA), and the Australian Securities and Investments Commission. The RBA came out particularly strongly, warning that both the physical and transition risks of climate change are likely to have first-order economic effects[1]. When a central bank, a prudential regulator and a conduct regulator, with barely a hipster beard or hemp shirt between them, start warning that climate change is a financial risk, it’s clear that position is now orthodox economic thinking.

However, in a trend we see mirrored around the world, translating that conviction on the need for stronger action into a consensus on how best to act remains challenging. Debate has largely moved on from whether there is a threat that requires a response to questions about the urgency of threat, who should carry the financial burden of addressing it, and whether the benefits are worth the cost. These debates exist in nearly every country in the world, but they are especially sensitive in Australia, which counts iron ore, coal, natural gas, aluminium ores and crude petroleum among its top 10 national export earners[2].

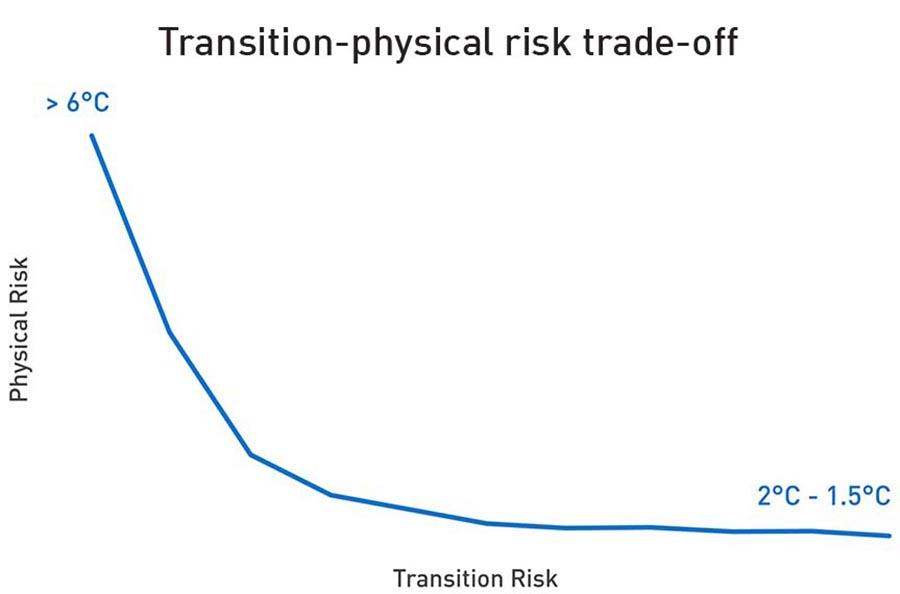

With the shift to the low carbon economy already underway, driven chiefly by the weight of money – consumer demand, investor decisions and regulatory responses – all economic participants face choices about the pace at which they are prepared and able to adjust. Regardless of their choice, some pain will be felt; the only questions being how much and when. We refer to this as the physical-transition risk trade-off, as shown here.

Source: Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures, The Use of Scenario Analysis in Disclosure of Climate-Related Risks and Opportunities, June 2017

In essence, what you see is an inverse relationship between the physical and transition risks of climate change. Taking aggressive mitigation action now, in line with meeting the world’s Paris Agreement targets, involves significant transition risks: taxes or the cost-of-living may rise, and jobs may be lost in some high-polluting industries. Government spending decisions may need to be reprioritised, and not every member of society will be able to bear these short-term costs equally comfortably. The benefit of such an approach is a substantial reduction in the expected catastrophic physical risks of climate change in the long-term.

Alternatively, transition risks can be minimised in the short-term by taking little or no action to reduce emissions or mitigate against their physical impact. The downside of this approach is pretty obvious. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), human activities have caused approximately 1.0 degree Celsius of global warming above pre-industrial levels. That’s well short of the 2 to 4 degrees Celsius rise predicted by 2100, yet already the physical impacts are being felt financially. Global insured losses in 2018 were roughly half of those in 2017, yet 2018 was still the fourth most costly year on record. The primary contributing factor was natural disasters, around 80 per cent of which were climate-related.

Two additional factors to work into that equation are liability risk and missed opportunities. Liability risk refers to the potential for companies, boards and individual directors to be held legally accountable for their actions – or lack of them – with regards to addressing climate risk. This was emphasised in 2016 with the release of an influential Australian legal opinion that found directors who failed to consider foreseeable climate risks “could be found liable for breaching their duty of care and diligence in future”[3] . That opinion was strengthened in March this year with an update asserting that the benchmark for directors to consider, disclose and respond to climate change was rising.

Furthermore, we should never forget that economic change presents opportunities as well as challenges. Forward-thinking businesses have for years been seeking to get ahead of the low-carbon curve by developing new products, expanding into untapped markets or investing in green finance opportunities. Companies that delay or avoid adjusting to new economic realities, no matter how famous or successful, can quickly find themselves on the verge of a Kodak moment.

The data deficit

So – controlled but aggressive change with a major short-term impact but lower long-term economic cost? Or uncontrolled change, limited short-term impact and much greater long-term economic damage?

When put like that, it seems such a straight-forward decision, but in reality, businesses around the world are struggling to find the appropriate balance, while satisfying their various stakeholders, be they shareholders, employees or customers. The scientific link between rising carbon emissions and warming temperatures may be irrefutable, but the data around how its impacts will unfold, and how to best manage them, remains badly under-developed, making informed debate challenging, misinformation rife and decision-making difficult.

Insurers, for example, are experts in assessing and pricing risk, but doing this accurately requires access to reliable data, such as such historical records, models and scientific analysis. If past experience is no longer a reliable guide as to what will happen in future, insurers’ ability to underwrite their policies and calculate premiums that keep the business competitive and profitable inevitably suffers.

The idea of a “data deficit” may seem counter-intuitive: it’s almost impossible to open a newspaper without encountering a story about yet another new report on climate change. But while climate scientists are blessed with some of the most accurate models yet created, the tools and methodologies for conducting climate risk analysis have a long way to go; the quality and availability of the data are limited; and further work is needed to translate the science into useful decision-making information. As a result, we face challenges assessing the way physical climate impacts will translate into asset level risks and exposures, as well modelling transition risks, in part due to general uncertainty about technological or policy responses. All businesses and governments face this challenge as they determine where to focus their money and effort: whether it be replacing car fleets with electric vehicles, divesting from fossil fuels, or modelling a future price on carbon when making investment decisions.

Exacerbating this is the absence of an accepted global standard for identifying, assessing, comparing, and disclosing climate risks and opportunities – the closet effort yet being the Financial Stability Board’s Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD). When it handed down its second status report a few weeks back, the TCFD reported a nearly 50 per cent increase in organisations that have expressed their support for the framework since September last year. Today, the TCFD is supported by almost 800 companies with a combined market capitalisation of around $10 trillion. But as impressive as that sounds, it’s still not enough. Those 800 companies are a fraction of the number of companies in the world, while that $10 trillion needs to be put in the context of a global GDP estimated at $88 trillion in 2018. On that basis, regulators are increasingly questioning whether market-led action alone will produce an uptake in TCFD compliance at the scale and speed necessary to avert damaging financial consequences down the track. As an aside, a poll of regulators and insurers at an IAIS event I attended in Buenos Aires last week voted 70 per cent in favour of climate risk disclosure being made mandatory.

Forward–thinking business leaders aren’t waiting to be pushed. By voluntarily committing to initiatives such as the TCFD, these companies are committing to identify, assess, manage and publicly disclose their climate risks. What these companies no doubt understand is that the very act of committing to disclose inevitably prompts them to take practical steps to enhance their business preparedness for the climate-related risks on the horizon. In order for a company to effectively disclose its exposure to the risks of global warming, and its potential opportunities, it needs to know what these are. Once these risks and opportunities have been identified, boards and executives are in a position to act to mitigate against risks and take advantage of opportunities, be they developing new products, expanding into untapped markets or investing in green finance opportunities.

Not only does this process assist the companies involved, expanding the pool of knowledge about what the risks are and how they intend to address them helps other economic actors –governments, regulators and businesses – inform their own transition plans. Speaking recently on the issue of cyber-crime, APRA Chair Wayne Byres called for closer collaboration within the financial sector to protect the national economy from organised crime[4]. I make the same argument in response to climate risk, adding, however, that this knowledge needs to be developed and shared across national borders given the consequences for the global economy. This collaboration is already taking place in the financial sector through organisations such as the UN Sustainable Insurance Forum, which I currently chair, and its banking equivalent, the Central Banks and Supervisors Network for Greening the Financial System’. All of us benefit from a strong and stable global economy; as RBA Deputy Governor Guy Debelle recently observed, financial stability is better served by an orderly transition to the low carbon economy rather than an abrupt disorderly one.

From awareness to action

As part of APRA’s efforts to increase understanding of climate risk, we conducted a survey last year of 38 of Australia’s largest banks, insurers and superannuation funds, and released the results in March[5].

The survey found the banking, general insurance and superannuation industries reported the highest awareness of climate risks. Life insurers and private health insurers were less likely to be taking steps to understand the risks, and less likely to view the risks as material to their businesses – a view they may be re-examining in the wake of Swiss Re’s recent SONAR report, which concluded that heatwaves, droughts, fires, and rapidly spreading diseases were among the biggest threats from global warming, and would have serious implications for life and health insurers[6].

Chart A – Organisations taking steps to improve their understanding of climate risk

Chart B – Organisations considering climate-related financial risk to be material

Tellingly, a separate APRA survey undertaken last year across Australian banks, general and life insurers listed climate change as the number one long-term financial risk, ahead of economic downturns and well ahead of cyber security.

Chart C – Major long-term risks faced by APRA-regulated entities

But we want to see that awareness translated into action, and the results on that front were patchier. Again, banks, general insurers and superannuation licensees were typically more advanced than life and private health insurers when it came to governance, risk management and strategy, including an awareness of opportunities. They were also more inclined than life or private health insurers towards disclosing climate-related risks, even though that is not yet specifically mandated.

Off the back of the findings, APRA is embedding the assessment of climate risk into our ongoing supervisory activities. We intend to probe the entities we regulate on their risk identification, measurement and mitigation strategies. We expect to see continuous improvement in how entities are preparing for the transition to the low-carbon economy. Additionally, in line with my earlier comments around the importance of broadening the pool of available knowledge, we are strongly encouraging entities to adopt the TCFD recommendations around disclosure. This is not something we are mandating, and nor do we intend to introduce a specific climate-related prudential standard at this time. However, I have previously noted that the global regulatory community is steadily moving in this direction[7], which is yet another reason why prescient business leaders should be taking steps now to get ahead of the curve.

Short-term pain for long-term gain

As society grapples to find the most effective and fair way to respond to the climate challenge, we sometimes hear voices trying to frame it as an economic, cost-of-living problem, rather than an environmental one. This is a false dichotomy. Climate risk is both an environmental problem and an economic one. Furthermore, that approach risks deceiving investors or consumers into believing there is no economic downside to acting slowly or not at all. In reality, we pay something now or we pay a lot more later. Either way, there is a cost.

Regardless of your views on the science, the transition to the low-carbon economy is underway and accelerating, presenting both risks and opportunities. New products, services and industries will rise, while others will decline, in response to changes in consumer and shareholder sentiment, variations in asset values and tougher environmental regulations. The financial sector, which funds, insures and invests in these businesses and industries will be heavily impacted by this transition, but it can also play a part in the solution.

By disclosing their climate risks and how they are addressing them in line with the TCFD recommendations, insurers, banks and superannuation funds put themselves in the best position to adjust to the new economic reality. More importantly, the availability of more timely, reliable and granular data will help all businesses, investors and regulators to better understand the transition-physical risk trade-off, and the reality that there is no avoiding the costs of adjusting to a low-carbon future. Taking strong, effective action now to promote an early, orderly economic transition is essential to minimising those costs and optimising the benefits. Those unwilling to buy into the need to do so will find they pay a far greater price in the long-run.

Footnotes

[1] https://www.rba.gov.au/speeches/2019/pdf/sp-dg-2019-03-12.pdf

[2] https://anz.businesschief.com/leadership/3663/Australias-top-10-exports

[3] Hutley, N and Hartford-Davis, S, Climate Change and Directors’ Duties, Memorandum of Opinion (7 October 2016)

[4] https://www.afr.com/business/banking-and-finance/banks-must-share-cyber-threat-intel-byres-20190516-p51o1z

[5] https://www.apra.gov.au/sites/default/files/climate_change_awareness_to_action_march_2019.pdf

[6] https://www.swissre.com/institute/research/sonar/sonar2019/sonar2019-climate-change-life-and-health.html

[7] https://www.cisl.cam.ac.uk/news/news-pdfs-or-prs/financial-exposure-geoff-summerhayes.pdf

The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) is the prudential regulator of the financial services industry. It oversees banks, mutuals, general insurance and reinsurance companies, life insurance, private health insurers, friendly societies, and most members of the superannuation industry. APRA currently supervises institutions holding around $9 trillion in assets for Australian depositors, policyholders and superannuation fund members.