Governance Review - Discussion Paper

Executive summary

Effective governance of banks, insurers and RSE licensees is fundamental to prudential regulation and sound risk management. Well-governed institutions are likely to be more resilient in times of stress. Poor governance creates weakness, which can crystallise in misconduct, losses and failures. This is evident both in Australia and overseas. Most of APRA’s supervisory and enforcement activity has involved issues that can be traced back to governance shortcomings.

As well as promoting sound prudential outcomes, good corporate governance practices are a necessary pre-condition for relaxing prudential requirements in other domains. To reduce overall regulatory burden without increasing risk, APRA must be confident that entities are led by high calibre, high integrity teams that can manage risk and govern effectively.

Over the past 10 years, APRA has devoted increased attention to governance, culture, remuneration and accountability. This work intensified in response to the Hayne Royal Commission and has become a focal point of APRA’s supervision. International standard setters and overseas regulators have also focused on strengthening governance practices among prudentially regulated entities.

APRA’s overall assessment is that governance practices have improved in recent years. This has been most pronounced among listed entities, and where APRA has specifically intervened to drive governance reform. APRA has seen examples of good practice across the sector, as reflected in its risk culture survey results and risk assessments of individual entities.

However, there remain substandard practices in some areas and regulated entities. APRA is determined to address remaining poor practices and set firm governance expectations for all regulated entities. Some of the main areas of corporate governance where APRA sees weakness include the skills and capabilities of directors, narrow approaches to assessing and reviewing fitness and propriety, insufficient attention to board performance assessments, problems stemming from overly long tenure and inadequate management of conflicts of interest.

This paper contains eight proposals to strengthen APRA’s core prudential standards and guidance on governance (currently set out in CPS 510 and SPS 510 Governance, CPS 520 and SPS 520 Fit and Proper, and SPS 521 Conflicts of Interest). The proposals aim to remedy areas of current poor practice and update APRA requirements to reflect contemporary governance standards.

Some of the proposals involve APRA being more prescriptive in its requirements. For example, in fitness and propriety, where entities have treated their obligations as a cursory ‘tick-a-box’ exercise that does not reflect the intent of the provisions. This is necessary to change the way these governance standards operate. As well as being clearer about APRA’s expectations, introduction of more ‘bright lines’ will assist APRA to use existing supervisory and enforcement powers where entities have not dealt with persistent issues. This could include a higher supervisory risk rating, requirements to undertake a risk transformation process, adjusting capital requirements, or ultimately, directing an entity to remove a director or applying to the court for a director’s disqualification.

At the same time, there are proposals to strip away unnecessary or duplicative rules and reduce burdens on regulated entities and their boards. Proposal 6 aims to help boards to delegate APRA requirements to board committees and senior management, freeing up time to focus on strategic issues that are more fundamental to enterprise governance.

APRA has considered the implications of the proposals for smaller regulated entities. Three of the eight proposals include exemptions for entities that are not significant financial institutions (non-SFIs). This reflects APRA’s view that governance arrangements need not look the same in every entity. Subject to meeting required minimum standards, governance practices should reflect an entity’s size, complexity and business model.

The proposals are not expected to materially increase costs for regulated entities with mature governance frameworks and practices. However, APRA recognises that the proposals on independence and tenure may temporarily increase turnover of existing directors. APRA seeks input from entities and directors on the costs and benefits of the package. This will inform more comprehensive analysis prior to finalising any updates to governance standards. APRA will also consult on transitional arrangements for different types of entities.

The proposals are based on current legislation and are consistent with APRA’s current powers. APRA has not made any proposals that would require legislative change. This means, for example, that one of the proposals only applies to banks and insurers, as the SIS Act does not empower APRA to make the corresponding change for RSE licensees.

As a package, the proposals are broadly consistent with relevant international standards and in line with or less interventionist than comparable overseas regimes.

Chapter 1 sets out the case for change, while Chapter 2 sets out the proposals on which feedback is sought. Chapter 3 provides more information about consultation and next steps.

APRA invites written submissions in response to this paper by 6 June 2025. APRA will also host industry and other stakeholder roundtables in April and May, to gather feedback and insights.

Proposals

1. Skills and capabilities

Require regulated entities to:

- identify and document the skills and capabilities necessary for the board overall, and for each individual director

- evaluate existing skills and capabilities of boards and individual directors

- take active steps to address gaps through professional development, succession planning and appointments.

2. Fitness and propriety

Require regulated entities to meet higher minimum requirements to ensure fitness and propriety of their responsible persons.

Require SFIs, and non-SFIs under heightened supervision, to engage proactively with APRA on potential appointments.

3. Conflicts management

Extend current RSE licensee conflict management requirements to banks and insurers so they are also required to:

- proactively identify actual and potential conflicts of interest and duty

- avoid or prudently manage conflicts

- take remedial action when conflicts are not disclosed or managed properly.

Require regulated entities to consider perceived conflicts, in addition to actual and potential conflicts.

4. Independence (banks and insurers only1)

Strengthen independence on regulated entity boards by:

- requiring that at least two of their independent directors (including the chair) are not members of any other board within the entity’s group

- making minor amendments to the independence criteria, including extending the prohibition on directors who are substantial shareholders in a regulated entity or group from being considered independent, to include material holdings of any type of security

- extending the current requirement for bank and insurer boards to have a majority of independent directors to include boards of entities with a parent that is regulated by APRA or an overseas equivalent.

5. Board performance review

Require SFIs to commission a qualified independent third-party performance assessment at least every three years which covers the board, committees and individual directors.

6. Role clarity

Define APRA’s core expectations of the board, the chair and senior management.

Provide additional guidance on which APRA requirements may be delegated to board committees and senior management.

7. Board committees

Extend the current requirement for bank and insurer boards to have separate risk and audit committees, to apply to SFI RSE licensees as well. Repeal this requirement for non-SFI banks and insurers, allowing flexibility for smaller entities.

Mandate that only full board members can be voting members of APRA-required board committees.

8. Director tenure and board renewal

Impose a lifetime default tenure limit of 10 years for non-executive directors at a regulated entity.

Require regulated entities to establish a robust, forward-looking process for board renewal.

Governance insights

Regulated industries and governance expectations have changed since APRA’s cross-industry governance standard was introduced in 2012

Assets held by APRA-regulated entities have grown from ~$4.2T to ~$9.1T. |  Assets held by APRA-regulated banks have grown 102%. | Assets held by APRA-regulated superannuation entities have grown 224%. |

New legislative accountability regimes came into force: banking (BEAR, 2018) then banks, insurers and RSE licensees (FAR, 2025). |  APRA has introduced several new prudential standards that include strong governance components – including for remuneration, operational risk management and information security. |  International supervisory standards and domestic benchmarks, such as the ASX Corporate Governance Principles, have been updated several times. |

When regulated entities are at heightened risk, there are often underlying governance issues

Of entities subject to heightened risk-based supervision, 78% have underlying governance issues. | Since 2018, APRA has accepted 7 Court-Enforceable Undertakings related to governance concerns. |  Since 2018, APRA has imposed 5 capital overlays for insurers, 7 capital overlays for banks, and 13 occasions of additional licence conditions for RSE licensees due to governance concerns. |

APRA seeks to address areas of persistent concern, and to empower boards to focus on what is most important

A recent cohort-based thematic review found almost 50% of boards of mutual banks had only one, or no directors with contemporary industry experience. | APRA’s prudential framework imposes 150 requirements on the average entity board.2 | Tenure of directors on boards of regulated entities > 10 years: 12%; |

Glossary

| ADI | Authorised deposit-taking institution |

|---|---|

| Accountable person | An accountable person as defined in s.10 of the FAR Act |

| ASX | Australian Securities Exchange |

| BCBS | Basel Committee on Banking Supervision |

| BEAR | Banking Executive Accountability Regime |

| Board | Board of directors of an institution or, for an RSE licensee, the Board of directors or group of individual trustees of an RSE licensee, as applicable |

| CPS 220 | Prudential Standard CPS 220 Risk Management |

| CPS 230 | Prudential Standard CPS 230 Operational Risk Management |

| CPS 234 | Prudential Standard CPS 234 Information Security |

| CPS 510 | Prudential Standard CPS 510 Governance |

| CPS 511 | Prudential Standard CPS 511 Remuneration |

| CPS 520 | Prudential Standard CPS 520 Fit and Proper |

| FAR Act | Financial Accountability Regime Act 2023 |

| IAIS | International Association of Insurance Supervisors |

| Non-executive director (NED) | A non-executive director as defined in paragraph 25 of CPS 510, and footnote 13 of SPS 510 |

| Responsible person | A responsible person as defined in paragraph 20 of CPS 520, and paragraph 12 of SPS 520 |

| RSE | Registrable superannuation entity |

| RSE licensee | Registrable superannuation entity licensee as defined in s.10(1) of the SIS Act |

| SFI | Significant financial institution3 |

| SIS Act | Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Act 1993 |

| SPG 510 | Prudential Practice Guide SPG 510 Governance |

| SPG 521 | Prudential Practice Guide SPG 521 Conflicts of Interest |

| SPS 220 | Prudential Standard SPS 220 Risk Management |

| SPS 510 | Prudential Standard SPS 510 Governance |

| SPS 520 | Prudential Standard SPS 520 Fit and Proper |

| SPS 521 | Prudential Standard SPS 521 Conflicts of Interest |

Chapter 1: Policy background

Governance comprises the principles, practices, processes and behaviours that determine how entities are directed and controlled. Boards have a central role to play in ensuring good governance as they are responsible for setting the strategic direction, culture and risk appetite of an institution, and for holding management to account.

APRA requires regulated entities to have effective governance arrangements to support boards in these roles. Such arrangements enable boards to make well-informed decisions, based on sound judgement and in the best interest of the entity and its key stakeholders or beneficiaries.

Good governance of financial services entities is essential

APRA-regulated entities play a central role in the economy and the lives of individual Australians. They protect savings, enable payments, provide access to credit, facilitate investment and help mitigate risk. The total assets of regulated entities have grown to around $9.1 trillion in 2024, up from $4.2 trillion in 2012 when CPS 510 was first consolidated from industry-specific standards. As well as having responsibility for this rapidly increasing pool of assets, entities face emerging risks including growing operational and cyber risks.

When regulated entities experience difficulties, the consequences can be dramatic for individual depositors, policyholders and superannuation beneficiaries, as well as for taxpayers and the broader economy. In APRA’s experience, well-governed entities are more resilient in times of stress, more agile in times of change, and demonstrate more sophisticated risk judgement. Instances of misconduct and poor performance are often ultimately found, in full or in part, to result from governance failures that allowed risky and inappropriate conduct to flourish.

Examples from Australia that highlight the importance of sound governance include the Hayne Royal Commission, the Commonwealth Bank of Australia (CBA) Prudential Inquiry and the Deloitte Independent Review into the trustee of Cbus, United Super Pty Limited. Some recent overseas examples include the reviews into the failures of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and Credit Suisse.

| The central role of governance, as emphasised by reviews and inquiries | |

|---|---|

Domestic Hayne Royal Commission ‘As often as possible, financial services entities should take proper steps to assess culture and governance, identify and deal with problems, and determine whether changes made have been effective.’ Royal Commission Final Report, February 2019. Commissioner Hayne emphasised the fundamental importance of leadership, governance, and culture in preventing misconduct. CBA Prudential Inquiry ‘Community trust in banks has been badly eroded, globally and in Australia…Governance weaknesses, serious professional misbehaviour, ethical lapses and compliance failures have resulted in substantial financial losses and record fines and penalties.’ Final Report of the Prudential Inquiry into the CBA, April 2018. APRA’s Prudential Inquiry stressed the need for effective governance and strong risk management culture to maintain trust and stability. | International Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) ‘Silicon Valley Bank’s board of directors and management failed to manage their risks...’ Federal Reserve Report, April 2023. The collapse of SVB highlighted significant governance failures, including insufficient risk management and internal controls. Credit Suisse ‘Owing to the inadequate implementation of its strategic focus areas, repeated scandals and management errors, Credit Suisse lost the confidence of its clients, investors and the markets. The resulting high level of withdrawals of client funds led to the risk of immediate insolvency in mid-March 2023.’ FINMA press release on its Report on the Credit Suisse Crisis, December 2023. FINMA analysed the bank's development from 2008 to 2023 and its own supervisory work. It identified key areas for improvement, including the need for stronger legal requirements, such as a Senior Managers Regime, and more stringent rules for corporate governance. |

APRA’s own supervisory and enforcement work supports the premise that governance shortcomings can lead to significant future problems for entities. Seventy-eight per cent of the entities currently subject to heightened supervision by APRA have underlying governance issues. This is consistent with APRA’s longer term supervisory experience. Almost all of APRA’s enforcement actions since 2018 have had risk governance and culture failings identified as the main underlying driver. APRA has imposed capital overlays for seven banks and five insurers, imposed additional licence conditions on thirteen separate occasions for RSE licensees, and accepted seven Court Enforceable Undertakings primarily due to weaknesses in governance.

APRA sets minimum expectations in concert with other regulation

Promoting effective governance is a fundamental part of prudential regulation. It is important that regulated entities are managed soundly and prudently, and that they are run by people with the right skills, experience and character.

APRA maintains foundational prudential standards for the governance of regulated entities as well as the fitness and propriety4 of directors, senior managers and other key office holders (referred to collectively as ‘responsible persons’5 ). There are also separate prudential standards governing other aspects of corporate governance including audit, remuneration, disclosure and risk management. APRA’s standards are reinforced by supplementary guidance and risk-based oversight, including reviews of industry practices. Much of APRA’s work is achieved through working directly with regulated entities. Wherever possible, APRA encourages boards and senior executives to drive change themselves.

APRA’s prudential requirements and guidance are only one part of the regulatory and legislative framework that applies to regulated entities and their directors. Examples of other relevant obligations can be found in:

- the Corporations Act 2001, administered principally by ASIC, which establishes key directors’ duties, such as the duty to act with reasonable care and diligence, the duty to act in good faith and for a proper purpose, as well as other statutory obligations and requirements.

- the Financial Accountability Regime Act 2023, jointly administered by APRA and ASIC, which introduced a strengthened responsibility and accountability framework for regulated entities as well as their directors and senior executives. This has come into effect for banks and commences on 15 March 2025 for insurers and RSE licensees.

- for RSE licensees, the introduction of the best financial interests duty (BFID) in 2021 and the retirement income covenant in 2022.

- for listed entities, the ASX Listing Rules and the ASX Corporate Governance Council’s Corporate Governance Principles and Recommendations.

APRA has made governance an enduring focus of its work

Over the past 10 years, APRA has devoted increased attention to governance, culture, remuneration and accountability. This work intensified in the wake of the Hayne Royal Commission and the Prudential Inquiry into the CBA, which emphasised the fundamental importance of sound governance and risk culture.

In recent years, APRA has introduced new cross-sector prudential standards for remuneration (CPS 511), operational risk management (CPS 230) and information security (CPS 234). APRA and ASIC have worked closely to implement the FAR, which strengthens responsibility and accountability for APRA-regulated entities.

In parallel, APRA has undertaken extensive supervisory work to assess governance arrangements of its regulated entities, which has enabled identification of good practices as well as remaining shortcomings. Where necessary, APRA has intervened to address instances of poor governance in individual entities. APRA has drawn on a suite of formal tools, such as additional capital overlays or licence conditions to ensure the issues and their underlying root causes are addressed. Nevertheless, there have been instances where stronger prudential standards may have prevented issues, or better enabled APRA to respond to governance shortcomings in a more timely and robust manner. This is most evident in cases where entities have been unwilling to recognise problems or claim they are complying with the letter of the relevant standard.

Governance practices have improved but there is more work to do

APRA’s judgement is that the overall quality of governance in regulated entities has improved since the Hayne Royal Commission. However, poor practices remain in some areas and regulated entities. Some key areas where APRA has observed weakness are the skills and capabilities of directors, narrow approaches to fitness and propriety, insufficient attention to board performance assessments, inadequate management of conflicts of interest, and problems stemming from overly long tenure.

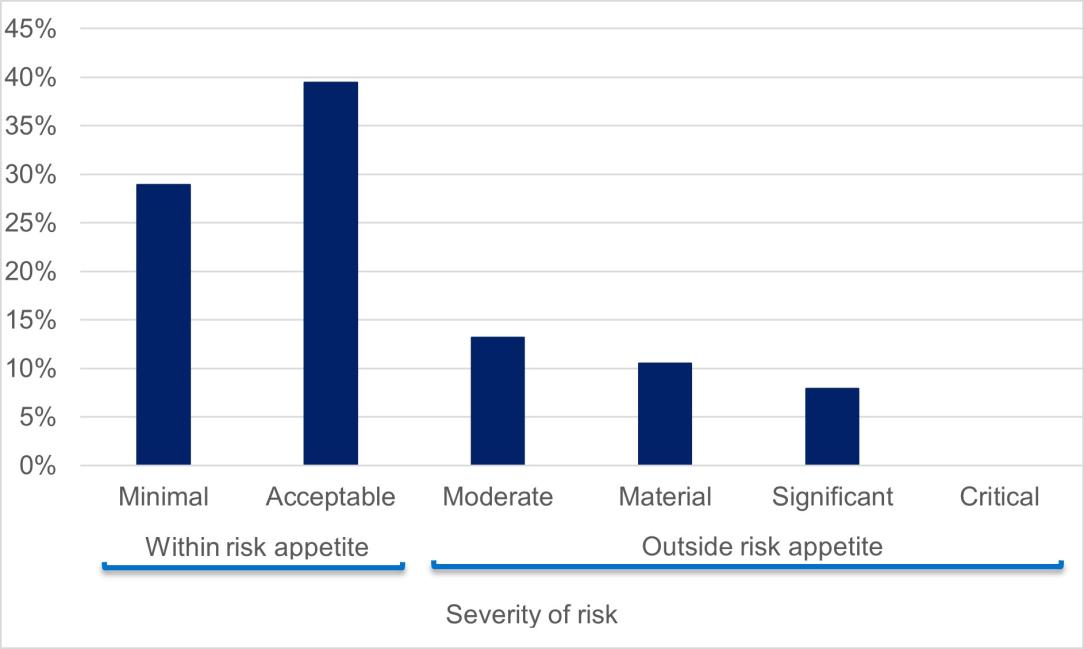

Under its Supervision Risk and Intensity (SRI) framework, APRA rates key risks for all banks, insurers and RSE licensees. The chart below shows the distribution of APRA’s ratings for governance risk for Tier 1 and 2 entities (typically larger, more complex entities).

APRA’s supervisory governance risk ratings – February 2025

The chart above indicates that governance risk for around 68 per cent of regulated entities is rated as being within APRA’s risk appetite (either rated as minimal or acceptable risk), supporting the view that the sector is, in the main, well-governed. However, there are still areas of poor practice, which cause entities to shift into higher risk categories resulting in more intense supervision by APRA. Reflecting these remaining shortcomings, 32 per cent of entities are assessed as having governance risks which fall outside APRA’s risk appetite: around 24 per cent have moderate or material risks, with 8 per cent of entities rated as having significant risks.6

A note about APRA’s existing supervisory and enforcement tools

If APRA is concerned about the governance of a regulated entity, it may use a range of tools and powers to ensure compliance. For example, APRA may:

- share thematic insights from a cohort or industry and issue recommendations

- increase the entity’s risk rating, supervisory intensity and/or adjust capital requirements or licence conditions to require the entity to address the issue and any underlying causes

- pursue remedies under the FAR

- direct the entity to remove a director or apply to the court for a director's disqualification.

Updating and clarifying APRA’s governance standards will provide a firmer basis for use of some of these tools.

Governance is an increasing focus for regulators and standard setters internationally

In developing the proposals in this paper, APRA engaged with overseas prudential regulators and considered developments in relevant international standards.

APRA found that overseas regulators are also placing greater emphasis on governance as a keystone of prudential regulation. Where governance practices are sound, prudential risks are more likely to be well managed. Some international regulators are taking a more interventionist approach to governance issues. Several have explicitly argued that the twin ‘cornerstones’ of an effective supervisory regime are the ability to take an active role in appointments, and a strong accountability regime (like Australia’s FAR) which holds those individuals responsible for risks and obligations.

Peer regulators also highlighted the importance of two other issues. The first is the value of independent verification and assessment of board and director performance. The second is the need for non-executive directors to be free from material conflicts, such as those arising from group associations.

Since APRA released its own prudential standards on governance, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) and the International Association of Insurance Supervisors (IAIS) have updated their own guidance for supervisors. Some of the key governance changes include a stronger emphasis on the skills and capabilities of directors, the need for directors to devote sufficient time to their roles, the importance of robust processes for selection of directors and senior managers, and risk governance in financial institutions.

In general, APRA considers that the proposals in this paper would help to bring Australia’s prudential framework for governance more closely into line with relevant international standards and overseas practice. Reflecting the importance that they attach to effective governance, some overseas jurisdictions have gone further than Australia by giving their regulators a statutory power to approve or veto appointments to regulated entities. Pursuing a similar approach in Australia would require legislative change, which is beyond the scope of this review. However, APRA proposes in this paper that some entities (SFIs and non-SFIs subject to heightened supervision) should engage more closely with APRA in the appointment process and that entities should improve their succession planning and appointment processes.

Proposal 8 is the only proposal that is significantly more prescriptive than overseas frameworks and standards. This would introduce a 10-year limit on director tenure at an individual regulated entity for non-executive directors. The issue of long-tenured directors has persisted at a number of regulated entities, and this has prompted APRA to propose a hard limit. APRA is not aware of other jurisdictions with a similar hard limit, other than as criteria for the independence of directors. Overseas regulators have advised that excessive director tenure is uncommon, which they attribute to their powers to intervene in reappointments.

The governance review

It is time to update APRA’s core governance standards. Boards and senior managers of regulated entities are the primary guardians of financial services governance, but strengthening prudential requirements will set clearer expectations and better enable APRA to address unresolved governance shortcomings and to measure entity and sectoral progress over time. Chapter 2 sets out the rationale for each of the eight proposals in this paper.

Scope SPS 510 Governance CPS 520 Fit and Proper SPS 520 Fit and Proper SPS 521 Conflicts of Interest Associated prudential practice guides | Objectives Update minimum governance standards. Apply proportionality and reduce compliance burden where possible. Strengthen APRA’s capacity to address remaining areas of poor governance practice. | Desired outcome Stronger governance practices improve risk management and reduce potential for misconduct, loss and failure. |

Chapter 3 provides more information about consultation and timeline for the review.

Compliance costs and proportionality considerations

APRA acknowledges the challenges associated with regulatory change in a fast-changing environment. There will be some compliance costs associated with these proposals. For instance, some regulated entities will have to establish more robust requirements for assessing the skills and capabilities as well as the fitness and propriety of their directors. Others will have to undertake more intensive reviews of board and director performance. Some large RSE licensees have yet to establish a dedicated risk committee.

Compliance costs associated with these proposals are expected to fall on regulated entities that have the weakest governance practices. They should not be material for entities with mature governance frameworks that already meet APRA’s standards, guidance and supervisory expectations. APRA considers the benefits of stronger governance processes for prudential soundness outweigh the relatively small and concentrated costs involved in implementing more robust governance processes.

At the same time, this paper also proposes some measures that have the potential to reduce compliance costs and regulatory burden for regulated entities. These include proposals that seek to: reduce overlap between APRA’s fit and proper requirements and the FAR (Proposal 2); clarify the role of boards and which matters can be delegated to board committees and senior management (Proposal 6); and provide increased flexibility on board committees for non-SFI banks and insurers (Proposal 7).

APRA also recognises that regulated entities may have to change the composition of their boards to meet proposed requirements on independence (Proposal 4) and tenure (Proposal 8). APRA is aware there are a range of views about the supply of capable directors. Some argue that it can be difficult to recruit directors for regulated entities given the potential liability and compliance obligations. For smaller entities, there can sometimes be additional challenges in recruiting directors with the necessary skills and capabilities. However, APRA has also heard contrary arguments that there are well-qualified directors available and willing to serve on boards.

APRA seeks feedback on the compliance implications of these proposals, including entities’ capacity to recruit appropriately skilled and qualified directors. APRA recognises that transitional arrangements will be necessary for some entities to comply with new requirements. APRA welcomes feedback on specific areas where non-SFIs may require more time than SFIs to facilitate smooth implementation.

In recent years, APRA has incorporated proportionality more explicitly into its prudential framework. While APRA has some minimum expectations in relation to governance, regulated entities are still able to comply with these proposals in a manner that is appropriate and commensurate with, and appropriate to the size and complexity of their business. For instance, APRA expects all regulated entities to have a risk management framework. Compliance with this requirement will naturally be more onerous and resource-intensive for a large, listed entity than for a small mutually owned entity. In some cases, APRA has gone further, by setting simpler requirements for smaller and less complex entities that are not non-SFIs. For example, APRA incorporated simpler requirements for non-SFIs in standards on remuneration and bank capital and has stated that it will use the SFI distinction to embed proportionality more broadly as it reviews and updates other standards.

Five of the proposals in this paper apply to both SFIs and non-SFIs. This is because they are focused on ensuring good governance standards for all, although their implications will depend on the size and complexity of an entity’s business model. Three of the proposals (Proposals 2, 5 and 7) involve lesser requirements for non-SFIs. While APRA has observed that some shortcomings in governance practices may be more prevalent among smaller entities, it considers that these can be addressed without imposing all the requirements that would apply to SFIs.

Chapter 2: Proposals

This chapter sets out APRA’s proposals to update its governance requirements. These are informed by APRA’s supervisory experience and international and domestic standard setters.

Proposal 1 – Skills and capabilities

Require regulated entities to:

- identify and document the skills and capabilities necessary for the board overall, and for each individual director

- evaluate existing skills and capabilities of boards and individual directors

- take active steps to address gaps through professional development, succession planning and appointments.

Current requirements

Prudential standards CPS 510 and SPS 510 require boards collectively to have the necessary skills, knowledge and experience to manage regulated entities appropriately. Each director must have ‘skills that allow them to make an effective contribution to board deliberations and processes.’ Boards are required to evaluate their collective performance on an annual basis. There is no explicit requirement to set minimum requirements for individual directors or to respond to any shortcomings.

Problem statement

Regulated entities have substantial discretion as to how they define their skill and capability needs, and how to assess the extent to which their boards and directors satisfy these requirements. As a result, APRA has observed wide variation in the effectiveness of these processes. While many entities adopt a robust forward-looking approach and take care to ensure their boards have the necessary skills and capabilities to support their strategy, others adopt more cursory processes and fail to address gaps. Shortcomings APRA observes include:

- adopting a vague or a narrow view of necessary skills and capabilities, including a failure to specify expected experience, qualifications or behavioural capabilities – and failing to consider how these can be measured

- failure to specify minimum skills and capabilities that individual directors need to fulfil their role

- not verifying skills or capabilities, often relying heavily on self-assessments

- failure to take steps to address gaps and weaknesses through professional development and succession planning.

These kinds of deficiencies tend to be most prevalent among small banks and in parts of the superannuation sector. For example, a 2021 cohort-based thematic review of mutual banks found that almost 50 per cent of boards had no directors or only one director with contemporary industry experience. Some RSE licensees have boards that are deficient against their own skills matrices, for example not having directors adequately skilled in key areas such as investment and risk management. However, APRA notes such issues are present in all industry cohorts.

Ongoing failure to address skill and capability needs will result in boards that are inadequately prepared to deliver on their organisational strategy or to anticipate and address challenges that arise.

Addressing the problem

APRA proposes to require all regulated entities to, on an ongoing basis, identify and document the skills, capabilities and behavioural attributes that the board needs to deliver its organisational strategy and perform its role. These attributes should be clearly defined and documented in a skills matrix. They should include specific expectations for the chair, chairs of board committees and other individual directors. Skills should be measurable and verifiable, and behavioural attributes should be observable. The targeted skills, capabilities and minimum criteria should be proportionate to an entity’s business needs, size and complexity.

Second, APRA proposes to require regulated entities to evaluate the skills and capabilities their boards already have and be able to demonstrate to APRA that they are taking active steps to remedy gaps through professional development, succession planning and new appointments. In considering nominees to the board, APRA expects entities to consider existing skills gaps so that each new appointment makes progress towards addressing them.

This proposal is intended to raise minimum standards for directors and boards across the financial system, irrespective of the nominations process or board structure. Requisite skills should be considered by those making the nomination. It should not impact entities that already adopt proactive and forward-looking approaches to board capability. Listed entities are already subject to similar expectations under the ASX Corporate Governance Principles and Recommendations.

These changes would also better allow APRA to hold regulated entities to account for the calibre and development of their boards.

To be clear, this proposal, as well as Proposal 2 below, would not involve any changes to the equal representation model under which employer and employee groups have the right to nominate directors to some RSE licensee boards. The focus of the proposals is on ensuring that directors of these entities have the necessary skills, capabilities and character – regardless of how they are nominated, the ownership model or board composition requirements in legislation.

Links with other proposals

Proposals 1 and 2 overlap and reinforce one another. A regulated entity’s fit and proper regime (Proposal 2) should set and assess a baseline of acceptable behaviour, character and qualifications to be on a financial services board or in other responsible person roles (effectively, being fit and proper is the ‘ticket to play’ as an industry leader). Proposal 1 should inform regulated entities’ assessment of whether a fit and proper individual is the right fit for their board. Specifically, entities would need to identify for their own board the specific skills and capabilities mix needed to deliver their organisational strategy – and act to achieve it. Lack of skill and capability should inform ongoing fit and proper assessments and therefore a director's prospects for reappointment. It should also flow through into board renewal and succession planning (Proposal 8). Triennial reviews of SFI board and director performance (Proposal 5) will verify progress on skills and capabilities, and make recommendations as needed.

Proposal 2 – Fitness and propriety

Require regulated entities to meet higher minimum requirements to ensure fitness and propriety of their responsible persons.

Require SFIs, and non-SFIs under heightened supervision, to engage proactively with APRA on potential appointments.

Current requirements

Fit and proper policies are a key part of a regulated entity’s risk management framework.

Regulated entities must prudently manage the risks that responsible persons who are not fit and proper pose to their business and financial standing. Entities must have policies and procedures for determining the fitness and propriety of responsible persons, including directors, senior managers and certain other individuals prescribed by industry legislation, including auditors and actuaries.

The definition of fitness and propriety encompasses a person’s core skills, experience and knowledge as well as their honesty and integrity. Conflicts are to be considered as part of the assessment, although there is no reference to potential or perceived conflicts. While APRA guidance lists matters that should be considered by a regulated entity in considering the fitness and propriety of a responsible person, it is generally left up to the entity to decide.

Fitness and propriety must, except in very limited circumstances, be assessed prior to initial appointment and reassessed at least annually. Regulated entities are obliged to conduct a full reassessment of a responsible person’s fitness and propriety if concerns emerge, but are not obliged to notify APRA unless they determine that person is not fit and proper. Where an individual is assessed as not fit and proper, the entity must take all reasonable steps to ensure that they are not appointed to, or do not continue to hold, a responsible person position. Entity policies must specify actions to be taken in those instances.

There is no requirement in the relevant prudential standards for regulated entities to consider important matters such as time capacity to fulfill the role, all criminal offences7 or reputational risk.

Problem statement

APRA has observed substantial variation in how regulated entities conduct fitness and propriety assessments. Poor practice is typically characterised by a narrowly defined process that fails to generate meaningful outcomes. For instance, APRA observes weaknesses such as:

- entities being focused on process compliance rather than outcomes

- taking a narrow view of what constitutes fitness and propriety8

- inadequate consideration of a person’s fitness (skills, capabilities, experience and knowledge)

- little consideration of the capacity of directors to balance multiple roles and professional obligations

- limited verification, with excessive reliance on self-assessments and other ‘light touch’ checks

- treating annual reviews of incumbent responsible persons as cursory exercises, rather than part of an enduring obligation to ensure the ongoing fitness and propriety of responsible persons.

On occasion, regulated entities have been unwilling to initiate a reassessment of a responsible person’s fitness and propriety where concerns emerge, even where they created reputational or prudential risk to the entity. There have also been instances where entities have been reluctant to engage with APRA where APRA has held concerns about the fitness and propriety of potential appointees.

Addressing the problem

APRA proposes to strengthen baseline expectations for fitness and propriety by:

- reinforcing entities’ responsibility for outcomes, as well as following a robust process set out in their fit and proper policy

- being more specific about what fit and proper means, and the need to verify conclusions. APRA proposes to incorporate existing guidance and additional matters into the standard for consideration, such as:

- actual, potential and perceived conflicts of interest and duties

- criminal and conduct records, for example contraventions arising out of civil, criminal or regulatory matters that may give rise to concerns

- character or regulatory references to evaluate performance in other roles, including the financial and reputational performance of previous organisations

- the ability to commit sufficient time to their role, including consideration of specific roles on other boards, for example chair or committee chair

- reputational risk.

- clarifying triggers for a fit and proper reassessment, for example:

- there are grounds to believe that an individual is not meeting their obligations under FAR, or otherwise not meeting minimum fitness or performance expectations

- material misconduct or behaviour inconsistent with an entity’s code of conduct

- adverse findings in criminal, civil or professional proceedings

- changes in personal circumstances posing potential reputational risk.

- requiring regulated entities to notify APRA when concerns arise that may reasonably impact a person’s fitness and propriety, even before a determination has been reached.

As set out in Chapter 1, several overseas jurisdictions can approve or veto appointments to prudentially regulated entities.9 While APRA does not have formal approval or veto powers, APRA seeks to heighten its oversight of, and entity focus on, the suitability of individuals in responsible person roles.

The FAR requires regulated entities to take reasonable steps to deal with APRA in an ‘open, constructive and cooperative way’. Consistent with this obligation, and to enable APRA to form a view of potential and incumbent responsible persons, APRA proposes to:

- enable APRA to require an entity-led reassessment if concerns about a responsible person or candidate are not addressed by the entity in a timely manner. For example, a reassessment may be prompted in response to material regulatory findings (e.g. via prudential review) or performance assessment (e.g. via board performance review)

- require that SFIs, and non-SFIs subject to heightened supervision, keep APRA informed of succession plans and nominations prior to appointment or public announcement

- in prudential practice guidance, note that APRA may request an interview with any candidates for responsible person roles, prior to appointment or reappointment. This is on an exceptions basis, where further information is needed to allay any concerns it may have.

Where APRA is not satisfied with a regulated entity's proposed or incumbent responsible person(s) or board performance, APRA will share its views with the regulated entity. If the entity does not act to address concerns, this will inform the intensity of APRA supervision. APRA may also trigger a reassessment of an individual’s fitness and propriety if they are already in a responsible person role (Proposal 2) or use its other supervisory or enforcement powers to address outstanding risk to the regulated entity.

In strengthening their fitness and propriety regimes, APRA also expects regulated entities’ written agreements with their accountable persons will adhere to both fit and proper criteria and the FAR.

Links with other proposals

This proposal complements Proposal 1 (skills and capabilities) as minimum director skills will overlap with broader fit and proper criteria. This proposal also relates to Proposal 3 (conflicts management). APRA seeks to ensure that all entities integrate forward-looking skills assessments with their fit and proper processes. APRA’s approach to conflicts aims to minimise structural conflicts by ensuring that they are routinely identified and addressed.

Links with FAR

There is some overlap between the reporting obligations that apply to regulated entities under APRA’s fitness and propriety requirements and statutory requirements under the FAR. The FAR has commenced for banks and commences on 15 March 2025 for insurers and RSE licensees. To reduce reporting obligations, APRA will examine whether it can align role definitions and rely on reports it receives under the FAR rather than requiring two sets of reports (although this will not apply to categories of responsible persons who are not accountable persons under the FAR).

Proposal 3 – Conflicts management

Extend current RSE licensee conflict management requirements to banks and insurers so they are also required to:

- proactively identify actual and potential conflicts of interest and duty

- avoid or prudently manage conflicts

- take remedial action when conflicts are not disclosed or managed properly.

Require regulated entities to consider perceived conflicts, in addition to actual and potential conflicts.

Current requirements

To be considered fit and proper, responsible persons of banks, insurers and RSE licensees must either have no conflict of interest in performing their duties or, if the person has a conflict, it would be prudent for a regulated entity to conclude that the conflict will not create a material risk that the person will fail to perform their duties properly.

More broadly, banks and insurers have different conflict management prudential obligations to RSE licensees. The risk management standard CPS 220 requires bank and insurer risk management policies and procedures to include a process for identifying, monitoring and managing potential and actual conflicts of interest.

RSE licensees are subject to a separate standard on conflicts of interest (SPS 521), which is more detailed and applies for the purposes of section 52(2)(d)(iv) of the SIS Act. The standard requires RSE licensees to:

- have a conflicts management framework to identify, assess, mitigate, manage and monitor all conflicts

- develop, implement and review a conflicts management policy that is approved by the board

- identify all relevant duties and relevant interests

- develop registers of relevant duties and relevant interests and make them public

The associated guidance (SPG 521) provides more insights about avoiding and managing conflicts.

Across all three industries, there are no requirements in the standards covering perceived conflicts, nor is there any explicit obligation to have regard to reputational risk.

Problem statement

APRA’s current requirements are inconsistent across its regulated industries. APRA has observed some weakness in entities’ identification and treatment of conflicts across the regulated population. The most common challenges relate to personal financial dealings of responsible persons, directors performing multiple roles within a group, relationships with suppliers, and personal affiliations.

Across regulated industries, there have been instances of inadequate identification of conflicts with service providers and responsible persons’ group affiliations. Some entities do not have adequate processes for identifying and managing director conflicts on a continuous basis, other than through declarations at board meetings. There have also been instances where directors and senior managers have held roles or had relationships, either directly or through family relationships, with service providers, and these conflicts were not appropriately addressed.

Contemporary good practice generally involves officers and directors identifying actual, potential and perceived conflicts of interest; disclosing these conflicts to the board and other stakeholders; actively managing conflicts including through recusal from decisions and structural changes where necessary; and documenting and sharing information as appropriate.

Addressing the problem

To address the issue of differing conflict management requirements across sectors, APRA proposes to create a single cross-industry set of requirements. This would include requirements that currently apply only to RSE licensees (e.g. having a conflicts management policy, and the public disclosure of registers of duties and interests). It is proposed that all regulated entities would be subject to these requirements. However, APRA seeks feedback on whether banks and insurers should be required to maintain and disclose registers of duties and interests and what the effect of this would be.

APRA also proposes to strengthen the requirements that are currently in SPS 521 by incorporating some material that is currently in the guidance into obligations, which would apply to all regulated industries. This includes the guidance that, as well as actual conflicts, potential or perceived conflicts and conflicts that affect the reputation of the business should be actively managed. This will ensure entities, and if necessary, APRA, can respond more effectively to instances of poor conflict management.

APRA will also use this as an opportunity to streamline certain requirements which currently apply to RSE licensees under SPS 521. For example, the standard requires an annual and triennial review of a fund’s conflicts management framework. For SFIs, the annual conflicts framework review may be integrated into the triennial board review outlined in Proposal 5.

Links with other proposals

This proposal is connected to Proposal 2 (fitness and propriety) where APRA expects that consideration of an actual, potential or perceived conflict will be a component of the fit and proper assessment. APRA is also proposing that review of the conflicts management framework should be incorporated into the triennial board review (Proposal 5). Finally, Proposal 4 seeks to reinforce the expectation that independent directors can exercise truly independent judgement.

Proposal 4 – Independence

Note: This proposal relates to banking and insurance entities only. The definition of independence for RSE licensees is prescribed by legislation and would not be affected by this proposal.

Strengthen independence on regulated entity boards by:

- requiring that at least two of their independent directors (including the chair) are not members of any other board within the entity’s group

- making minor amendments to the independence criteria, including extending the prohibition on directors who are substantial shareholders in a regulated entity or group from being considered independent, to include material holdings of any type of security

- extending the current requirement for bank and insurer boards to have a majority of independent directors to include boards of entities with a parent that is regulated by APRA or an overseas equivalent.

Current requirements

APRA prudential standard CPS 510 requires boards of banks and insurers to have an independent chair and a majority of independent directors. An independent director is currently defined as:

‘a non-executive director who is free from any business or other association — including those arising out of a substantial shareholding, involvement in past management or as a supplier, customer or adviser — that could materially interfere with the exercise of their independent judgement.’

CPS 510 allows the independent directors on the board of the parent company or its other subsidiaries to sit as independent directors on the board of the regulated entity.

The standard also prohibits directors who are substantial shareholders in a regulated entity or group from being considered independent.

While APRA-regulated boards in banking and insurance must generally have a majority of independent directors, locally incorporated entities that are subsidiaries of a prudentially regulated parent have slightly different requirements. The boards of these subsidiaries must have a majority of non-executive directors, but they do not all need to be independent. CPS 510 requires three independent directors (including the chair) on a board of up to seven directors, and four (including the chair) on larger boards.

Problem statement

Intra-group conflicts

As noted in relation to Proposal 3 (conflicts management), APRA has observed instances of poor conflict management where entities do not fully consider potential or actual intra-group conflicts, particularly in the context of board members. APRA has seen instances where directors considered to be independent under the current prudential standard have shown a lack of independent judgment by failing to prioritise the best interests of an APRA-regulated entity over other group entities.

APRA’s observation is that the current prudential standard does not take sufficient account of the potential for conflict between the interests of different group entities. The extent of these conflicts varies across groups. At one end of the spectrum, there are groups where interests are well aligned. In these cases, independent directors can serve on multiple boards and not encounter significant conflicts. At the other end, there are groups where interests are not well aligned. In these groups there is much higher potential for conflict between the interests of the regulated entity and other group entities. Particularly where conflicts of interest between parent and subsidiary exist, APRA has intervened to require entities to address these conflicts by restructuring boards, taking specific actions to address conflicts, and appointing additional independent directors. In some instances, APRA has imposed capital overlays to encourage these governance concerns to be addressed.

Other conflicts

While CPS 510 prohibits directors who are substantial shareholders in a regulated entity or group from being considered independent, it does not acknowledge that holding other types of securities may create similar conflicts which may interfere with a director’s judgement.

Inconsistent requirements for board composition

CPS 510 sets inconsistent requirements for bank and insurer entity boards. While there were concerns about available directors for subsidiaries with APRA-regulated parents or overseas equivalents more than a decade ago, there is limited evidence to support different treatment now.

Addressing the problem

A proposed revised definition of independence is provided below. APRA welcomes feedback on this definition:

‘a non-executive director who is not an employee of the entity, or the group to which it belongs, and who is free from any business or personal relationship that interferes, or could reasonably be perceived to interfere, with their exercise of objective judgement or acting in the interests of the regulated entity.’

Intra-group conflicts

There are several ways APRA could address this issue in its prudential standards. All options involve trade-offs between supervisory efficiency, entities’ ease of application, risk mitigation and industry disruption. They range from removing the current clause which allows directors to sit on multiple boards and retain their independent status, through to mandating that independent directors on the board of a regulated entity cannot sit on other boards within the group.10 The former would involve considerable review and judgement by entities, in consultation with APRA, to determine which directors are independent. The latter would cause considerable disruption and director turnover, even where entity and group interests are highly aligned.

To strike a pragmatic balance between these objectives, APRA proposes to mandate that on each regulated entity board, at least two of the independent directors (including the chair) must not be directors on any other board within the relevant group.

Irrespective of which option is ultimately chosen, APRA expects regulated entities to effectively manage intra-group conflicts for every member of their board.

Other conflicts

APRA also proposes to update the criteria currently in Attachment A of CPS 510 to ensure that substantial holders of any security issued by the regulated entity or the group to which it belongs cannot be considered independent. The original intent remains the same - to prevent material financial conflicts. The amendment would simply acknowledge that substantial debt holders, for example, may be subject to the same influence as substantial equity holders.

Consistent requirements for board composition

APRA proposes to extend the requirement for bank and insurer boards to have a majority of independent directors, to also apply to subsidiaries of parents regulated by APRA or overseas equivalent. APRA is conscious that the proposed changes may require recruitment of additional independent directors, and a reasonable transition period. Any final requirements that would require changes to board composition would embed suitable transitional arrangements for affected banks and insurers.

Proposal 5 – Board performance review

Require SFIs to commission a qualified independent third-party performance assessment at least every three years which covers the board, committees and individual directors.

Current requirements

APRA standards require boards of all regulated entities to have procedures for assessing board and individual director performance at least annually. APRA’s guidance for the boards of health insurers and RSE licensees (HPG 510 and SPG 510) sets the expectation that the assessment of board performance should by undertaken by an external party at least every three years.

Problem statement

APRA’s supervisory experience is that board performance assessments vary substantially in scope and depth. Some reviews are thorough and forward-looking, while others lack rigour and credibility. Some entities commission external board reviews, although these can still fall short of expectations. APRA reviews of performance assessments have identified three key areas where reviews have scope to improve:

- they focus on the collective board and do not capture committee and individual director performance

- they are not informed by robust evidence, instead relying solely on self-assessments or peer input

- chairs fail to take a leadership role, either in the assessment process or in ensuring that emerging recommendations are addressed.

The ASX Corporate Governance Principles and Recommendations for listed entities support the principle that performance assessments should cover individual directors and committees, stating that listed entities should ‘have and disclose a process for periodically evaluating the performance of the board, its committees, and individual directors.’ The principles also encourage considering periodic use of external facilitators. The Australian Institute of Company Directors (AICD) has similarly recognised the value of internal and external board evaluations.

Addressing the problem

To address these problems, and to take a proportionate response, APRA proposes to require SFIs to:

- commission external independent performance assessments of boards, committees and individual directors by credible and appropriately qualified experts every three years

- have their chair take a leading and accountable role for the satisfactory completion of performance assessments and for ensuring that recommendations are addressed appropriately

- submit the independent triennial report to APRA.

Given the anticipated rigour of the triennial review, APRA expects to narrow the scope of annual performance assessments for SFIs (to focus on progress on recommendations from the independent assessment).

APRA recognises that commissioning an external board assessment may be disproportionately costly for smaller entities and has stopped short of mandating this exercise for non-SFIs. However, APRA still expects non-SFIs to improve the overall quality and rigour of their annual performance reviews. Non-SFI chairs are also expected to take active leadership of the process and resulting programme. This will be reflected in guidance.

APRA proposes SFI triennial external reviews would cover, at minimum:

- board, committees and individual director performance

- engagement between directors and senior management

- the chair’s effectiveness

- board and committee workloads and meeting cadence

- quality of reporting to enable risk-based decision-making and oversight

- conflicts management

- strategic alignment of the skills matrix and gap analysis against current state

- effectiveness of overall decision-making.

The independent assessment should recommend tangible actions that will assist the board and its committees to be more effective. Findings should feed into renewal and succession planning, skills matrices and, where relevant, fit and proper assessments. Boards of SFIs must be able to demonstrate to supervisors how they are acting upon the recommendations of external reviews.

Proposal 6 – Role clarity

Define APRA’s core expectations of the board, the chair and senior management.

Provide additional guidance on which APRA requirements may be delegated to board committees and senior management.

Current requirements

APRA standards include a short, high-level definition of the role of the board of a regulated entity (‘the board is ultimately responsible for the sound and prudent management of the institution’). They include even less on expectations concerning the role of the chair. Detailed guidance on what boards should do is limited to the roles and responsibilities of board audit, risk and remuneration committees. This contrasts with other relevant standard setters, including the BCBS, the IAIS and the ASX Corporate Governance Council, which each provide guidance in their principles on the role of the board.

CPS 510 gives authority to the board of a regulated entity to delegate responsibilities to senior management. Delegations must be in writing and boards must have systems in place to monitor the exercise of delegated authority. Boards remain ultimately responsible for matters delegated to management.

Problem statement

APRA has observed a tendency for some board agendas to be overweight on operational matters, sometimes at the expense of strategic issues. An APRA governance thematic review found that many boards were spending less than 30 per cent of their time on forward-looking strategy and risk oversight.

APRA’s current prudential requirements and guidance relating to boards have emerged over many years. The prudential standards currently set around 150 requirements for a typical entity board. Of these requirements, about 25 per cent relate to reports to the board. A further 25 per cent require the board to review or approve specific matters. The remainder assign responsibility to boards for oversight or management of specific prudential obligations. APRA has received feedback that it would help entities if prudential standards and guidance were clearer about the core responsibilities of the board, and what can be delegated to board committees or senior management.

The final report of the prudential inquiry into the CBA emphasised the importance of boards holding management to account, and management providing the board and committees with sufficient and succinct information to make effective decisions.

The prudential inquiry into the CBA also emphasised the crucial contribution of board chairs to effective governance. APRA has observed poor outcomes at some regulated entities where chairs have failed to provide adequate leadership and oversight of board functions. These include lack of challenge to management, groupthink, a failure to include relevant stakeholders in deliberations and insufficient attention to board performance and renewal.

Addressing the problem

To address these problems, APRA proposes to amend its prudential standards to include a clear articulation of the primary roles of the board, the chair and senior management. While APRA appreciates that most APRA-regulated boards understand their responsibilities, the purpose of the proposal is to be clear on APRA’s expectations, and to facilitate better delegation to board committees and management. This should empower boards to spend more time on forward-looking strategy, risk and oversight.

Responsibilities APRA considers to be central to the board include:

- articulating the purpose and values of the entity, and desired culture

- overseeing development, approval and execution of the entity’s strategy, objectives and risk appetite

- overseeing the effectiveness of governance and risk management frameworks

- providing leadership and constructive challenge to senior management.

APRA also proposes to identify the core responsibilities of the chair in prudential standards. APRA expects that this would include responsibility for culture, board performance and fit and proper assessments.

In relation to the role of senior management, APRA proposes an outcomes-focused definition that supports the execution of the regulated entity’s activities in line with the board-approved strategy, risk appetite, culture and values, and ensures senior management deals with the board in a clear, timely and transparent manner. Senior management should be responsible for briefing the board effectively, with succinct and relevant information to support decision making, rather than briefing with a view to satisfy compliance requirements.

While CPS 510 and SPS 510 already allow boards to delegate certain functions to senior management and board committees, APRA is seeking feedback on more specific examples of processes and policies APRA has assigned to the board that would be appropriate for delegation to committees or senior management.

APRA will also commit, as it revises other prudential standards, to review existing requirements placed on boards to ensure that they remain appropriate.

Links with other proposals

As the board is responsible for overall governance, oversight and strategic direction, this proposal overlaps with all the other proposals. The proposal to clarify the key role of board chairs in prudential standards overlaps with Proposal 2 (fitness and propriety) and Proposal 5 (board performance review), under which chairs would have explicit responsibility for the assessment process and for ensuring that recommendations are addressed and fed into succession planning.

Proposal 7 – Board committees

Extend the current requirement for bank and insurer boards to have separate risk and audit committees, to apply to SFI RSE licensees as well. Repeal this requirement for non-SFI banks and insurers, allowing flexibility for smaller entities.

Mandate that only full board members can be voting members of APRA-required board committees.

Current requirements

APRA currently requires banking and insurance boards to maintain separate risk and audit committees. RSE licensee boards are only required to have an audit committee, whose responsibilities include risk. There is no requirement for a separate risk committee.

For all industries, there are no provisions that prevent non-board members of board committees, such as external advisers, from voting on committee matters.

Problem statement

APRA requires banks and insurers to establish separate audit and risk committees to help ensure that adequate time, focus, skill and experience are allocated to matters in line with three lines of defence principles. Consistent with contemporary good practice, most large RSE licensees have already established separate risk committees. In some instances where there is no separate risk committee, APRA has observed weaker risk oversight and risk capability.

APRA has observed the practice of external experts joining board committees of RSE licensees. These individuals can have specialist skills that are lacking among board members. APRA is not opposed to external advisers attending and advising committees. However, APRA considers that external advisers should not be full voting members, and they should not be relied upon to resolve critical board skills gaps.11

Addressing the problem

While having separate risk and audit committees is better practice, APRA recognises that this may create additional cost and complexity for smaller entities (non-SFIs). APRA therefore proposes to remove the current requirement for all bank and insurers to separate these committees.

For SFIs, APRA proposes to extend the requirement for separate committees to RSE licensees that are classified as SFIs. The aim is to sharpen the focus of large and systemically important RSE licensees on risk governance and underpin the effectiveness of the three lines of defence.

APRA also proposes to specify that only full board members can be voting members of APRA-mandated committees. This reflects APRA’s view that boards should address gaps in skills and capabilities through appropriate director appointments, succession planning and training. Advisers may continue to attend committee meetings to provide expert advice and complement director experience. Restricting voting to full board members is intended to ensure clear board accountability.

Links with other proposals

This proposal links to Proposal 1 (skills and capabilities) and Proposal 5 (board performance review).

Proposal 8 – Director tenure and board renewal

Impose a lifetime default tenure limit of 10 years for non-executive directors at a regulated entity.

Require regulated entities to establish a robust, forward-looking process for board renewal.

Current requirements

APRA standards require boards to have a formal policy on board renewal. These policies must consider whether directors have served for a period that could, or be perceived to, materially interfere with their ability to act in the best interests of the regulated entity. Requirements for RSE licensees are more prescriptive, with SPS 510 mandating that policies must state maximum tenure limits. The associated guidance states that APRA expects there are limited circumstances in which tenure limits beyond 12 years would be appropriate.

Problem statement

Appropriate limits on director tenure are an important part of good governance. Well managed turnover of directors facilitates stability, continuity and expertise – while also promoting fresh ideas and renewal. Overly long tenure is likely to erode a director’s capacity to exercise impartial judgement and to challenge management effectively. It can limit openness to new ideas and different approaches and be a barrier to an unvarnished assessment of an entity’s culture.

An APRA governance thematic review of ADI mutuals found that while many directors agree that long tenure can erode their ability to challenge management, some boards find it difficult to address these concerns effectively. Entities continue to convey to APRA that it can be difficult for chairs and directors to challenge colleagues on this issue.

Over the years APRA has invested considerable effort to address instances of overly long tenure in certain cohorts where this has been a widespread issue. While some progress has been made, APRA assesses that there remain almost 200 directors with tenure greater than 10 years, including almost 150 directors with tenure greater than 12 years. This does not account for instances in which a merger has effectively ‘reset the clock’ for director tenure. Around 30 directors have tenures over 20 years. To put this data in context, APRA estimates there are around 1,500 non-executive directors across all APRA-regulated entities. Approaches to board renewal are varied. While entities generally comply with the requirement to have a formal renewal policy, APRA has observed several weaknesses. These include lack of specificity about appointment processes, limited connection to board skills matrices, and a lack of early and effective succession planning.

Addressing the problem

APRA proposes to introduce a 10-year lifetime tenure limit on a regulated entity board for non-executive directors, with the possibility of an extension at APRA’s discretion. This includes where an entity has undergone a merger. The purpose of this proposal is to establish a consistent and appropriate baseline in the prudential framework to which all regulated entities will be held.

APRA acknowledges there are genuine trade-offs associated with this proposal. Many directors of long tenure are highly experienced and make a strong contribution throughout their directorships. For this reason, APRA proposes to reserve the right to make case-by-case exceptions upon entity application. This would allow APRA to grant a two-year extension in limited and exceptional circumstances. This approach seeks to strike a balance, recognising both the benefits and risks associated with long tenure.

Introduction of a 10-year tenure limit is consistent with contemporary governance benchmarks and the relevant literature, which suggest that independent non-executive directors should ideally serve for a maximum period of between nine and 12 years. Overseas prudential regulators have not set hard limits on non-executive director tenure, although several have issued guidance to indicate that director independence may be affected after 10 years on a board. APRA recognises that introducing a firm time limit would make Australia’s framework more prescriptive. However, APRA considers this is justified because, unlike some regulators, it lacks formal power to address tenure through the reappointment process, and excessive tenure remains an issue despite considerable supervisory suasion.

In implementing this proposal, APRA will be mindful of the need to provide regulated entities with sufficient time to implement the new requirements. APRA would welcome feedback from industry on the type of transitional arrangements that may be necessary.

With respect to board renewal, APRA proposes to extend the current prudential requirements to explicitly require:

- consideration of the full cycle from nomination and appointments through to succession planning

- detail on director nominations, appointment process, length of term and maximum number of terms

- how results of board and director performance assessments will feed into succession planning and renewal.

These changes are intended to drive renewal of regulated entity boards, and ensure those processes are integrated with other relevant considerations such as skills and tenure. In supervising these new requirements, it is anticipated that APRA will focus on outcomes. As such, an entity can either maintain a separate renewal policy, integrate renewal into its fit and proper policy or adopt another process that the entity deems appropriate.

Chapter 3: Consultation

In the three months following release of this discussion paper, APRA is seeking feedback from banks, insurers and RSE licensees, experienced company directors, industry, consumer and other associations, and other interested stakeholders. APRA is particularly interested in feedback on the potential costs and benefits of its proposals, opportunities to simplify and streamline the proposals without compromising their objectives, considerations for implementation, and proportionality.

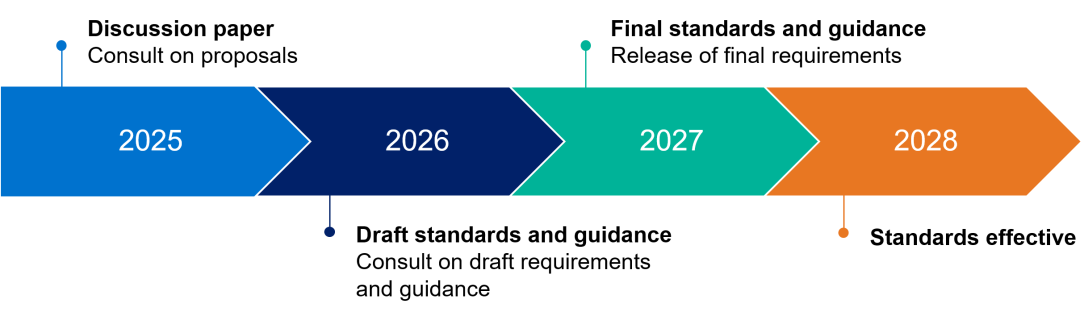

Governance review timeline

Request for submissions

APRA invites written submissions in response to this discussion paper. Submissions are welcome to address any aspect of the discussion paper. Stakeholders are also invited to provide views on the proposals and accompanying questions. They should be sent to PolicyDevelopment@apra.gov.au by 6 June 2025 and addressed to:

General Manager

Policy Development

Policy and Advice Division

Australian Prudential Regulation Authority

During the consultation period, APRA expects to hold roundtable discussions with industry and other stakeholders to explore the issues and options identified by this paper and their anticipated impacts. This engagement will inform draft revisions to governance requirements, consultation on which is expected to occur in H1 2026.

Important disclosure information

All information in submissions will be made available to the public on the APRA website unless a respondent expressly requests that all or part of the submission is to remain in confidence. Automatically generated confidentiality statements in emails do not suffice for this purpose.

Respondents who would like part of their submission to remain in confidence should provide this information marked as confidential in a separate attachment.

Submissions may be the subject of a request for access made under the Freedom of Information Act 1982 (FOIA). APRA will determine such requests, if any, in accordance with the provisions of the FOIA. Information in the submission about any APRA-regulated entity that is not in the public domain and that is identified as confidential will be protected by section 56 of the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority Act 1998 and will therefore be exempt from production under the FOIA.

Discussion paper questions

| Impact | Will the proposed changes achieve their goal of strengthening governance? What is the anticipated impact of the proposed changes (costs and benefits)? |

|---|---|

| Regulatory burden | Are there specific opportunities to simplify, reduce or optimise requirements without diluting policy intent? |

| Transition | What would assist a smooth transition to meet updated requirements? |