Discussion paper - Enhancing bank resilience: Additional Tier 1 Capital in Australia

Executive summary

Banking crisis events overseas earlier this year have provided important lessons for banks and regulators, including on the decisiveness and speed at which they need to be able to respond in stress. In June, the Council of Financial Regulators (CFR) discussed the new complexities and challenges faced by policy makers, and noted that it is assessing Australia’s crisis management settings to ensure they remain robust.1

A key area of focus for APRA as part of this assessment is the effectiveness of Additional Tier 1 capital (AT1).2 AT1 instruments are a critical part of banks’ financial resilience: they are designed to absorb losses in stress and provide capital to support bank resolution at the point of failure.

Enhancing financial resilience

It is important that AT1 operates as intended, to avoid the use of public money and safeguard depositor funds. There has been significant growth in AT1 instruments over time, which heightens the need for them to operate effectively.

APRA is reviewing the design of AT1 instruments to ensure they are fit for purpose, and can:

- stabilise a bank so that it can continue to operate as a going concern during a period of stress; and

- support resolution, with the capital that is needed to prevent a disorderly collapse.

There are currently certain design features and market practices that would create significant challenges, or potentially undermine, the effectiveness of AT1 in Australia:

- Rather than acting to stabilise a bank as a going concern in stress, international experience has shown that AT1 absorbs losses only at a very late stage of a crisis.3 This was evident most recently in the banking crisis events overseas in early 2023, where AT1 was used only at the point of non-viability; and

- Australia is an outlier internationally with a large proportion of AT1 held by domestic retail investors. This would make it particularly challenging to use AT1 to facilitate the recapitalisation of a bank in resolution, as APRA would be concerned that imposing losses on these investors would bring complexity, contagion risk and undermine confidence in the system in a crisis.

This Discussion Paper outlines potential options to improve the effectiveness of AT1, based on measures implemented internationally. The aim of these options is to ensure that AT1 can be used in practice to absorb losses if needed, to build confidence in the system in times of stress.

In weighing up potential options and determining whether the benefits to be gained from policy changes outweigh the costs, there will be a range of trade-offs to consider. It will be important to understand and clearly assess the benefits for financial resilience and impacts on banks, investors and the broader financial system.

While this Discussion Paper focuses on AT1 for banks, many of the challenges and issues also apply to AT1 issued by insurers. APRA expects that proposed revisions to the prudential standards for banks would also be made, where relevant, to the corresponding standards for insurers.

Next steps

APRA requests feedback on the questions outlined in this Discussion Paper by 15 November 2023. In addition, APRA intends to hold roundtable discussions with banking and insurance industry associations and is open to meeting with key stakeholders to ensure the full range of options and their impacts are well understood. Following subsequent discussions at the CFR, APRA intends to formally consult in 2024 on any proposed amendments to prudential standards.

Footnotes

1 Quarterly Statement by the Council of Financial Regulators – June 2023.

2 AT1 is hybrid capital: bonds that absorb losses in stress through discretionary coupon payments that can be cancelled, and by converting into equity (or being written off) in a crisis.

3 This is because of a reluctance by banks to cancel coupons in periods of stress, and the low trigger level for bail-in of AT1 instruments. The challenges with using AT1 to stabilise a bank early are likely to be more acute in Australia than in other jurisdictions, given the investor base and low trigger level.

Chapter 1 - Purpose of AT1

This chapter provides an overview of the intended purpose of AT1 capital. AT1 plays an important role in bank capital and crisis management and is designed to absorb losses and stabilise entities in periods of stress and at the point of non-viability.4

Role of AT1

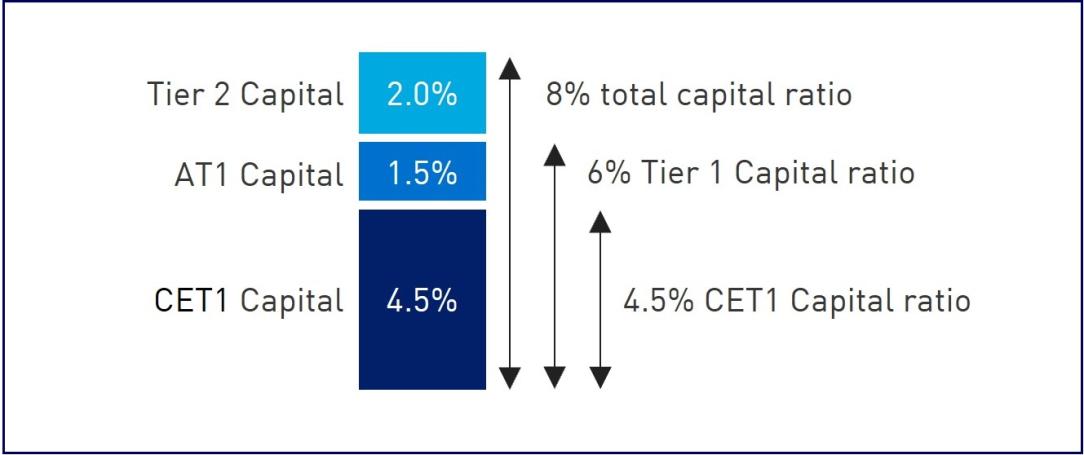

Capital is the cornerstone of a bank’s financial strength. It provides the financial resources to enable a bank to withstand periods of stress, and protects depositors in the event that the entity needs to be resolved. There are three types of regulatory capital, as set out in the table below.

Table 1. AT1 and how it compares to other forms of regulatory capital5

Type of capital | Absorbs losses | Permanence | Ranking | Distributions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

CET1 | All scenarios | Permanent | Most subordinated | Dividends (discretionary) |

AT1 | Severe stress and resolution | Permanent (no maturity date but may be callable) | Senior to CET1 | Distributions (discretionary) |

Tier 2 | Resolution | Maturity date (5+ years) | Senior to CET1 and AT1 | Coupons (mandatory) |

The three types of capital play different roles in providing financial support in each stage of stress:

- Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) capital, such as ordinary shares, is intended to be immediately available to absorb losses as they occur. CET1 can be used early and throughout a period of stress, when a bank needs capital to maintain confidence.

- Tier 2 capital, such as fixed-term subordinated bonds, is intended to be available during the resolution of a bank when it is at the point of non-viability. Tier 2 absorbs losses at this stage, facilitating orderly resolution options.

- AT1 capital sits between these two forms of capital in terms of seniority. It is designed to absorb losses as part of early crisis intervention to restore a bank’s capital position, and can be used as part of resolution if needed.

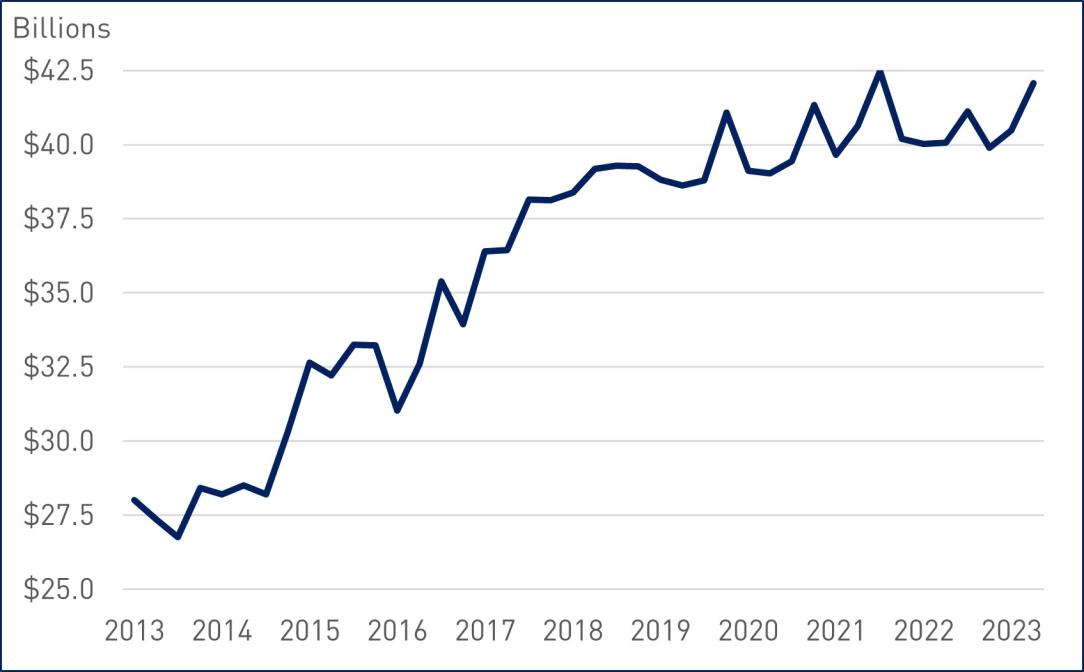

Box 1 outlines the origins and growth in AT1 capital over time. AT1 capital has become a key element of capital structures for Australian banks, which have around $40 billion outstanding (as at June 2023).

Box 1: Origins and growth of AT1 capital

AT1 in its present form has its origins in the aftermath of the global financial crisis (GFC). Following the GFC, regulators undertook fundamental reforms to the international banking regulatory framework, culminating in the Basel III standards. A key element of the reforms was to raise the quantity and quality of capital to improve banks’ financial resilience in periods of stress, which included the introduction of AT1 as it is defined today.

APRA introduced requirements for AT1 in Australia in 2013. As shown in the chart below, there has been significant growth in Australian AT1 outstanding over the past 10 years. AT1 has increased by around 50 per cent as banks have grown over the period. The predominant issuers are the major banks and Macquarie Bank, which account for over 85 per cent of Australian AT1.

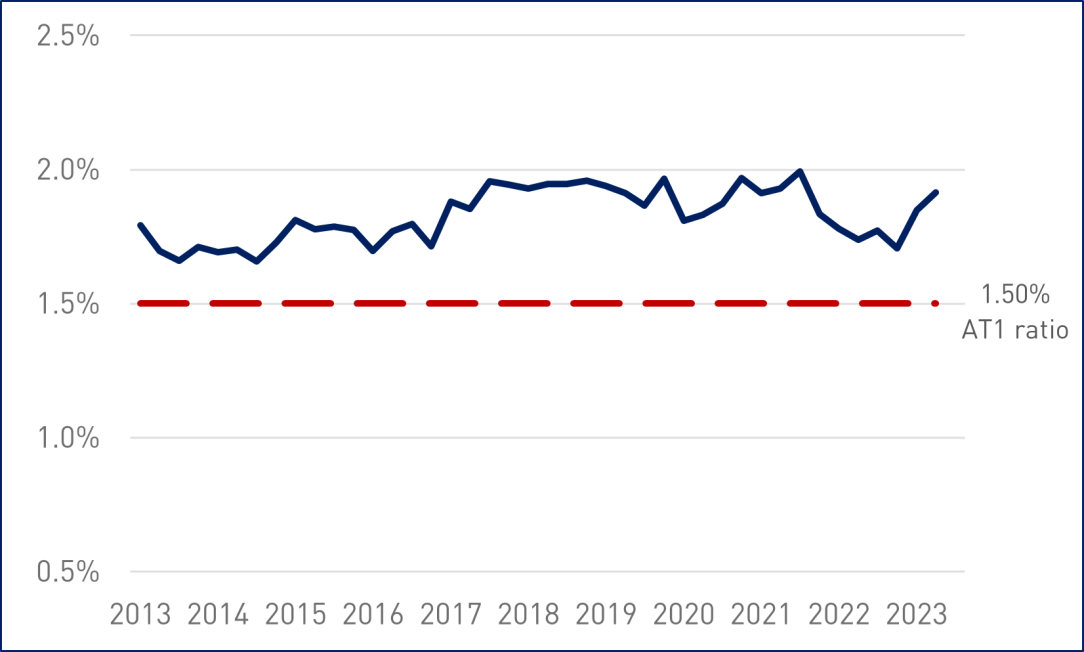

While the capital framework has evolved over the past 10 years, there have not been changes to AT1 requirements. Banks have consistently maintained a surplus of AT1 compared to requirements over time.

Figure 1. Total AT1 for banks

Figure 2. AT1 capital ratios for banks

Purpose of AT1 in stress

AT1 is intended to be used to stabilise a bank and support its financial resilience. It operates in two key phases of stress: early intervention and resolution. AT1 has a distinct role, as it is designed to act at an earlier stage than Tier 2 in stabilising a bank. In this phase, it is intended to support a bank to continue operations, and to complement other recovery actions such as raising capital and restructuring businesses if needed.

Without AT1, a bank would need more higher-cost CET1 to achieve the same level of financial resilience or would run a higher risk that it would not be able to weather stressed conditions. While banking crisis experience is limited in Australia, hybrid capital has been used overseas as part of crisis management. AT1’s intended role as a loss absorber in each of the two key phases is summarised in the table below.

Table 2. AT1 as a loss absorber

Phase | How AT1 is used |

|---|---|

Early intervention | In this phase, AT1 acts as a stabiliser for a stressed bank to support it to maintain operations. Unlike Tier 2, a bank can use AT1 in this phase to absorb losses by:

|

Resolution | In this phase, AT1 supports resolution where a bank is at the ‘point of non-viability’ (PONV). PONV is defined as the point at which APRA considers that, without conversion or write-off of capital instruments, or without a public sector injection of capital (or equivalent support), the bank would become non-viable. At this stage, AT1 would be converted or written-off to provide equity capital for the bank. |

Design of AT1

To ensure AT1 capital is designed appropriately to fulfill its purpose, there are international standards set by the Basel Committee. APRA prescribes specific requirements, based on the Basel standards, for the form and quantum of AT1 capital that needs to be held by banks. In considering policy changes, it will be important to ensure APRA requirements continue to meet the minimum standard set by the Basel Committee.

Box 2: Minimum capital requirements

Prudential Standard APS 110 Capital Adequacy (APS 110) sets out the minimum capital requirements for banks.6 The figure below summarises the minimum regulatory capital requirements for a bank, excluding capital buffers and additional loss-absorbing capacity requirements.7

The minimum level of Tier 1 required to be held by a bank is 6.0 per cent of RWA, of which 4.5 per cent must be met in CET1; the remaining 1.5 per cent is generally met with AT1. Specific criteria for capital instruments to qualify as AT1 are set out in Prudential Standard APS 111 Capital Adequacy: Measurement of Capital (APS 111).8

Figure 3. The minimum regulatory capital requirements for a bank

Some countries have included additional design features to enhance the effectiveness of AT1, beyond the Basel standards and beyond the current regulatory requirements that have been implemented in Australia. This includes higher trigger points for conversion and restrictions on the investor base for AT1. These additional design features are discussed further in the following chapters.

Footnotes

4 In consulting on the Basel III reforms, the Basel Committee noted that “it is critical that for non-common equity elements to be included in Tier 1 capital, they must also absorb losses while the bank remains a going concern. Qualifying instruments must contribute in a meaningful way to ensuring the going concern status of the bank and they must be capable of absorbing losses in practice without exacerbating a bank’s condition in a crisis.” - Strengthening the resilience of the banking sector (December 2009).

5 Table 1 is based on Prudential Standard APS 111 Capital Adequacy: Measurement of Capital (APS 111), which provides further detail on each type of regulatory capital.

6 Prudential capital requirements for general insurers, life companies and private health insurers are set out in Prudential Standard GPS 110 Capital Adequacy, Prudential Standard LPS 110 Capital Adequacy and Prudential Standard HPS 110 Capital Adequacy.

7 AT1 is also relevant in other areas of APRA’s prudential framework where requirements are based on Tier 1 capital levels, such as the leverage ratio and large exposure requirements. This Discussion Paper primarily focuses on the role of AT1 for loss absorbency.

8 Prudential Standard GPS 112 Capital Adequacy: Measurement of Capital (GPS 112), Prudential Standard LPS 112 Capital Adequacy: Measurement of Capital (LPS 112) and Prudential Standard HPS 112 Capital Adequacy: Measurement of Capital (HPS 112) are applicable for general insurers, life companies and private health insurers. APS 111, GPS 112, LPS 112 and HPS 112 also set out other components that make up CET1 and Tier 2 capital.

Chapter 2 - Challenges with AT1

This chapter summarises the key challenges with AT1. It reflects on lessons learned from recent and past international bank stress and highlights the challenges with AT1 in the context of the Australian market.

Key challenges

AT1 was introduced to improve the availability and flexibility of capital to absorb unexpected losses during times of stress. There have been, however, significant challenges internationally in using AT1 to absorb losses, both during early intervention and at the point of resolution. These key challenges are summarised in the table below, based on lessons learned internationally.

Table 3. Key challenges in using AT1 to absorb losses

Summary | Key challenges |

|---|---|

Challenges in using AT1 to absorb losses in early intervention | Banks have been reluctant, in practice, to cancel AT1 distributions to conserve capital given the market signalling effects The loss absorbing trigger for converting AT1 into equity (or writing it off), to support a bank as a going concern in stress, is too low to be reached in practice given normal operating targets and the speed of crises |

Risks of using AT1 to support resolution | The risks of converting AT1 into equity or writing it off include contagion, litigation and uncertainty. This is amplified where there is a high proportion of domestic retail investors, such as in Australia These risks complicate the quick decision-making needed in a crisis, and limits regulatory authorities’ ability to take the steps that may be needed to shore up confidence in the entity and broader system |

Early stage intervention

AT1 is designed to absorb losses at an earlier stage of a crisis than Tier 2: through cancelling discretionary distributions to conserve capital, akin to reducing dividend payments in stress, and through the loss absorbing trigger that converts AT1 to equity or writes it off to stabilise a bank as a going concern.

In practice, however, international experience has shown that AT1 has not been effective in absorbing losses at this stage:

- Distributions paid in stress: In its evaluation of the Basel III reforms, the Basel Committee has noted that distribution cancellations on AT1 can be difficult in practice, as they send a strong message to the market about non-viability; missing payments can result in a steep increase in pricing and low market demand for AT1 and other instruments.9 This was demonstrated in Switzerland this year, with the Swiss National Bank (SNB) noting that “the AT1 features designed for early loss absorption in a going concern were not effective.”10 Credit Suisse did not cancel payments on AT1 instruments despite incurring sustained losses and facing an uncertain profitability outlook.11

- Triggers set low: AT1 has not been converted at an early stage in a crisis in practice, as the trigger for it to be used is set at a relatively low level of capital. There would need to be a substantial drop in capital from normal operating targets before AT1 is triggered, which is unlikely in practice to be before the point of non-viability; the market will have typically lost confidence in the entity well before capital is depleted to these levels.

The challenges with the loss absorbing trigger for AT1 would also be accentuated by reporting lags on capital metrics, which are typically reported on a monthly or quarterly basis (with a month delay). In addition, other drivers of stability and market confidence beyond capital, such as liquidity risk, may be important triggers. In the case of Credit Suisse, the SNB noted that AT1 capital instruments absorbed losses only as the point of non-viability was imminent and state intervention became necessary. This was also the case with Banco Popular in Spain in 2017.

Box 3: Additional challenges in an Australian context

The challenges of using AT1 to absorb losses to stabilise a bank in the early stages of a crisis are likely to be more acute in Australia, for several reasons:

- investor expectations that distributions continue to be made in stress is likely to be strong, given the lack of crisis experience which has resulted in no AT1 distributions ever being missed;

- there can be a perception that AT1 operates more like debt instruments and therefore would not absorb losses early in stress. For example, APRA has been concerned that Australian banks have been under market pressure to treat AT1 as fixed term and call these instruments even when it is uneconomic to do so;12 and

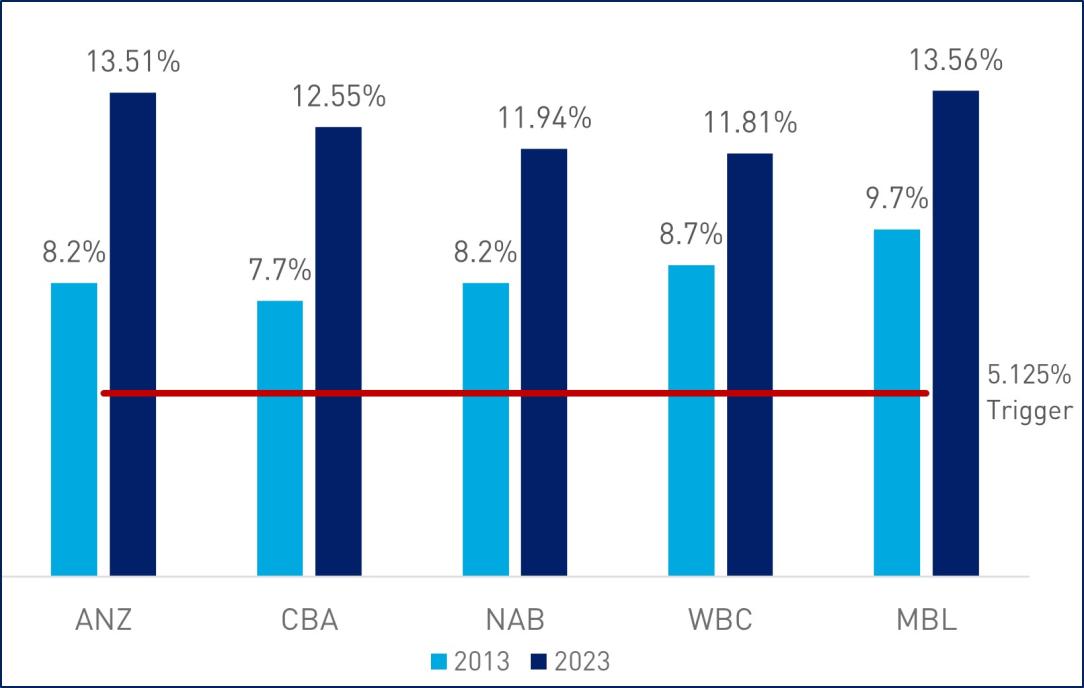

- the low trigger level for bail-in of AT1, which is set uniformly at a CET1 ratio of 5.125 per cent of RWAs, in contrast to market practice in some other jurisdictions.13

CET1 targets are typically above 11 per cent in Australia, which means a bank would need to sustain losses that deplete more than half of its capital base before the 5.125 per cent trigger is reached.14 As demonstrated by the speed of crisis events overseas, AT1 would need to be used more quickly than this to be effective in a going concern scenario, to bolster confidence in a bank in stress.

Figure 4. Australian bank capital levels relative to the AT1 trigger point

Risks in resolution

AT1 also plays a key role in supporting a bank’s resolution process. Although the risk of bank failure is low, it is important that regulators have effective crisis management tools to manage a bank at a critical stage of stress if it does occur.

As demonstrated by experience internationally, regulators need to be able to act swiftly and decisively to resolve banks at or near the point of non-viability. AT1 has been converted to equity or written off to absorb losses overseas, including earlier this year.

There are, however, significant risks in using AT1 as part of resolution where there is a high proportion of retail investors holding these instruments. These challenges can hamper the ability of authorities to shore up confidence and prevent a systemic crisis from worsening and prevent AT1 from meeting its purpose in resolution – to absorb losses instead of relying on public sector support.

The risks of using AT1 to support resolution where there is a high proportion of retail investors include:

- Challenges in absorbing losses: Rather than absorbing losses in resolution, internationally the use of AT1 has led in some cases to complications and risks being borne by the Government rather than investors. For example, in 2017, the Italian Government guaranteed AT1 instruments issued by two failing banks, given concerns about potential financial stability risks from bailing in retail investors. Similar risks with hybrid capital were evident during the banking crisis in Spain in 2008-2014; the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) noted that hybrid capital and subordinated debt instruments failed to deliver the expected resources to help recapitalise banks and led to litigation proceedings by hybrid capital holders to recover losses (which in turn had to be taken on by the Government).15

- Contagion risks: Bailing in AT1 at one bank is highly likely to lead to concerns about AT1 instruments at other banks, especially in a more homogeneous banking market and a more severe systemic crisis.16 It can also lead to broader contagion risks across the industry, as imposing losses on domestic AT1 investors creates an immediate feedback loop in the financial system, undermining confidence at a critical time in a crisis. This can be amplified by uncertainty where investors do not understand the risks they are exposed to.17

- Uncertainty in crisis decision-making: The recent crisis events in Switzerland and the US took place at unprecedented speed. Social media and the rapid spread of information accelerated the need for banks and regulators to make clear and quick decisions during resolution. The use of AT1 complicates decision-making in a crisis as regulators need to consider investor reactions, contagion risk and broader systemic impacts, amongst other factors, in making the PONV declaration and deciding how to use this capital in resolution.

These complications do not arise with CET1, which does not require a PONV declaration to be used or need to be converted. The risks are also less acute with Tier 2, given the lack of retail ownership of these instruments. However, as AT1 is used in a crisis prior to Tier 2, complications in AT1 would impede APRA’s ability to use Tier 2.

Box 4: Challenges of using AT1 in resolution in Australia

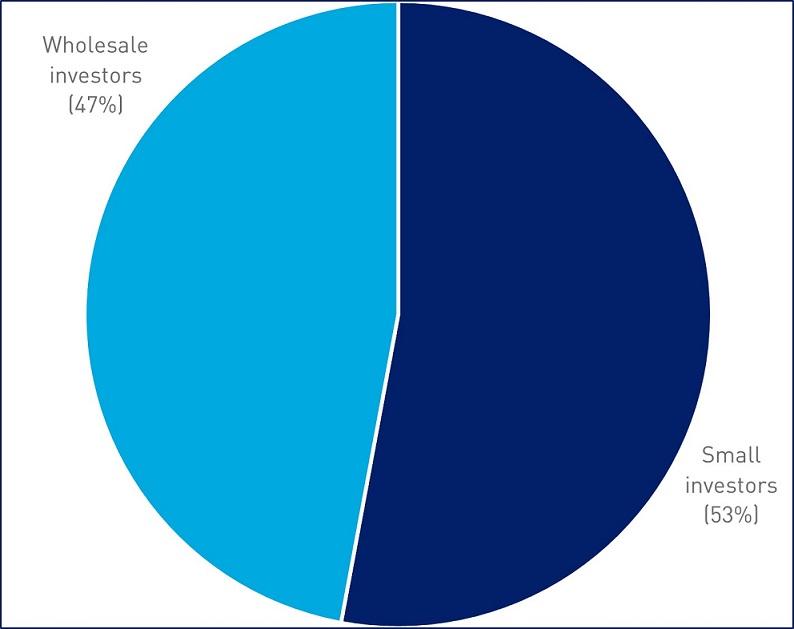

The challenges of using AT1 to support resolution are likely to be more acute in Australia, given the investor base. Retail investors are a prominent part of the Australian AT1 market, with around 50 per cent of investors in AT1 instruments listed on the ASX holding parcels smaller than $500,000 (above this level, investors would be classified as wholesale under the Corporations Act 2001).18

Australia is an outlier internationally in having such a high proportion of retail investors holding AT1 instruments. For example, in 2015, the UK Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) banned the distribution of contingent convertible instruments (equivalent to AT1) to retail investors.19 This followed the FCA noting that contingent capital are risky and complex instruments that even professional investors may struggle to evaluate and price properly.20 Other jurisdictions that have restricted or banned retail investment in AT1 include the EU, Switzerland, Canada and India.

Figure 5. AT1 outstanding (ASX-listed - March 2023)

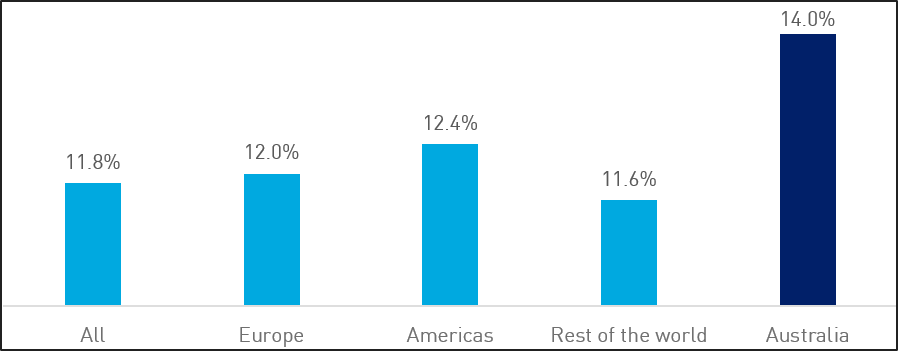

Australian banks also have a greater reliance on AT1 relative to international peers, which in turn exacerbates the complexities of using AT1. The surplus of AT1 may be driven by pricing levels and strong demand. In the US and Europe, banks tend to hold closer to the minimum capital requirements, rather than having a surplus of AT1.

Figure 6. AT1 as a proportion of Tier 1 Capital

Another concern arising from the banking crisis events earlier this year was the write-off (rather than conversion) of AT1, which raised questions around the creditor hierarchy. The use of write-off instruments is not a focus in this paper, given the limited number of these instruments in Australia (less than three per cent of bank and insurance AT1 issuance). However, this may be an area for clarification in the prudential standards in due course.

Footnotes

9 Basel Committee Evaluation of the impact and efficacy of the Basel III reforms (December 2022).

10 Swiss National Bank, Financial Stability Report (2023).

11 Banks’ reluctance to cancel distributions not only undermines the ability of AT1 to absorb losses, but also exacerbate other risks to ongoing financial stability: for example, where banks seek to avoid cancelling AT1 distributions by staying above regulatory buffers through reductions in lending to households and businesses.

12 APRA issued a letter in late 2022 setting out its expectations around calling capital instruments: Expectations on capital calls | APRA.

13 In some jurisdictions internationally, such as the UK, banks use a higher trigger for AT1 in practice. There can also be differences in regulatory requirements, with large banks in Switzerland for example being required to have a 7 per cent trigger.

14 The AT1 trigger level was designed in the aftermath of the global financial crisis, when CET1 ratios were significantly lower. Today, banks tend to operate at levels significantly above this, meaning that the trigger point would only be reached in the late stages of a crisis after there were significant losses.

15 Bank for International Settlements (BIS), FSI Crisis Management Series No.4, The 2008-14 banking crisis in Spain (July 2023).

16 While there can be contagion risks from the use of any form of capital, AT1 is a much more complex product; it is more difficult for investors to understand when and how AT1 will be used. This lack of clarity for investors was evident during the bail-in of AT1 capital for Credit Suisse earlier this year, which resulted in contagion risk across the AT1 market; there were losses for AT1 investors, and the market was closed to new issuance.

17 The European Banking Authority (EBA) and European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA), for example, have noted these contagion risks, which may affect overall confidence in financial markets. See Statement of the EBA and ESMA on the treatment of retail holdings of debt financial instruments subject to the Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (30 May 2018).

18 The Government is currently reviewing the definition of wholesale investor: Review of the regulatory framework for managed investment schemes - consultation | Treasury.gov.au.

19 Restrictions on the retail distribution of regulatory capital instruments, FCA (June 2015).

20 Temporary product intervention rules, FCA (August 2014).

Chapter 3 - Enhancing AT1 in Australia

Given the challenges outlined above, APRA is exploring options to improve the effectiveness of AT1. The aim of these options is to improve the ability of AT1 to absorb losses to support a bank as a going concern and during resolution. This chapter sets out three broad policy approaches that APRA may consider, and outlines some potential trade-offs and impacts that would need to be assessed.

Potential policy options

The policy options outlined below are not mutually exclusive, and could reinforce each other if implemented in combination. APRA welcomes feedback on these and any other options that may enhance the operation of AT1 capital.

Table 4. Summary of potential options

1. Design of AT1 | Improving key design features to ensure AT1 more effectively absorbs losses and can be used earlier to stabilise a bank in stress. |

2. Role of AT1 | Reducing reliance on AT1 by changes to the level or mix of regulatory capital requirements. |

3. Participation in AT1 | Changes to diversify the AT1 investor base away from domestic retail investors. |

Design of AT1

Under the first potential option, APRA could seek to improve the design of AT1 instruments. The aim of this approach would be to ensure that AT1 can effectively absorb losses at an earlier stage in stress. This would better enable AT1 to fulfill its role as hybrid capital in stabilising a bank, rather than only at a late stage during resolution.

There is a range of ways that this could be achieved, including, for example, by:

- adjusting constraints on capital distributions when banks are under stress. For example, APRA could change or add to the intervention points that constrain AT1 capital distributions when a bank enters the capital conservation buffer range or is making losses; and/or

- adjusting the operation of the loss absorbency trigger. For example, APRA could consider raising the loss absorbing trigger level, or redefining it. Raising the trigger from the current 5.125 per cent to a higher level would prompt earlier use of AT1, as would expanding the definition of the trigger to base it on more forward-looking metrics.

Moving the loss absorbing trigger level higher has been implemented in some other jurisdictions. The Basel Committee has noted that market practice has resulted in some AT1 capital instruments featuring a trigger that is higher than 5.125 per cent; for example, with a 7 per cent CET1 ratio trigger being used in some jurisdictions.

Role of AT1

Under the second potential option, APRA could reduce the role of AT1 in the capital framework. Reducing the level of AT1 would shift reliance to other forms of capital that do not carry the same challenges as AT1. The greater the reliance on AT1, the greater the scale of contagion and complexity in resolution as there would be more AT1 capital converted or written off during stress.

To reduce the role of AT1, APRA could make changes to the level or mix of regulatory capital requirements.

There is a range of ways that this could be achieved including, for example, by:

- reducing the level of AT1 capital, offset by a commensurate increase in other capital requirements; and/or

- capping the maximum amount of capital that is eligible to be counted as AT1, to ensure banks are not overly reliant on these instruments.

Participation in AT1

Under the third potential option, APRA could seek to reduce the risks resulting from the high level of retail ownership by amending the eligibility criteria for AT1 to include conditions on the investor base.

This approach would align with international practice that restricts retail ownership of AT1. It would diversify the investor base away from domestic retail investors, reducing contagion risk in the Australian financial system. It would also help to ensure these complex instruments are only held by investors who are best placed to absorb losses and understand the risks they are taking on, reducing uncertainty in a crisis.

To achieve this objective APRA could amend the eligibility criteria in APS 111 for AT1 to count as regulatory capital, with certain additional qualifying conditions. There is a range of ways these conditions could be defined including, for example, by requiring minimum denominations for parcel sizes in which AT1 capital could be sold to effectively restrict participation to wholesale investors.21

While disclosure has a role in improving investor understanding of the risks of AT1, this option would be unlikely in APRA’s view to sufficiently address the challenges with these instruments. Despite existing disclosure obligations, the complexity and opacity of AT1, including how it would change in value and nature in stress, makes it very difficult for even sophisticated investors to understand.22 Relying on disclosures alone would also be inconsistent with approaches taken by other regulators internationally.23

Policy considerations

The policy approaches outlined above would improve the effectiveness of AT1. However, as with any policy proposals, there are important trade-offs and consequences that need to be evaluated. Key considerations are outlined in the table below.

In implementing options, APRA expects that there would be transition time to enable banks to adjust to new requirements. This would, for example, include transition time if needed for existing AT1 instruments to be replaced to ensure an orderly adjustment.

Table 5. Policy considerations

Issue | Key considerations |

|---|---|

Heightened costs and market impacts | Changes to the level or mix of capital requirements, design of AT1 or investor base would likely lead to increased funding costs for issuers and other market impacts. The scale of the impacts would depend critically on the type of changes made and calibration: for example, a more material change in the level of AT1 would have a more significant cost (and benefit). Specific considerations include:

It will be important to understand how banks and investors would adapt to changes in regulatory requirements, including the capacity of domestic and offshore markets to absorb changes in issuance and how transition arrangements could affect pricing impacts. |

Alignment with international standards | Australia is a member of the Basel Committee and maintains prudential requirements that are at least equal to internationally agreed minimum standards. In considering changes to the prudential standards, it will be important that Australia continues to meet these international standards, which can limit the extent of policy change. |

Strength of the capital framework | APRA calibrates its capital framework to ensure Australian banks are financially resilient and can withstand future shocks to the Australian economy. Amendments to the capital framework must not undermine the financial strength of the industry, such as by decreasing overall bank minimum capital requirements. |

Footnotes

21 Denominations prescribe the minimum parcel size that an investor could hold in that security. This would represent the minimum parcel size that the AT1 Capital instrument could be broken down to and therefore the minimum investment required to purchase the security (e.g. $500,000).

22 Banks are currently subject to principles-based design and distribution obligations (DDOs), which require AT1 issuers to take reasonable steps to distribute instruments in line with their target market determination. For further information, see Design and distribution obligations | ASIC. Some issuers are now requiring clients to obtain written confirmation from a financial advisor that the investor has received appropriate advice before they will distribute the product to the investor, or evidence that the client is a sophisticated investor within the meaning of the Corporations Act (such as evidence the client has net assets of at least $2.5 million). There has not been a material reduction in non-wholesale investor participation in new issues of AT1 instruments following the introduction of DDOs. Additionally, DDOs only apply to primary issuance of AT1, and not to trading or purchases on secondary markets.

23 For example, in implementing restrictions on retail investment in AT1, the UK FCA noted they did “not consider that other solutions on their own, such as additional disclosure, are likely to be sufficiently effective given the need for specialised knowledge, and the unfamiliar and untested nature of these investments.” See Restrictions on the retail distribution of regulatory capital instruments, FCA (October 2014).

Chapter 4 - Providing feedback to APRA

Discussion questions

APRA welcomes feedback on the specific policy questions provided in the below table, in addition to general feedback on the issues raised in the Discussion Paper.

Table 6. Discussion questions

Questions |

1. What are the best policy options for improving the effectiveness of AT1 to support resilience? |

2. What would be the impact of these options? |

3. What transition arrangements could soften these impacts? |

4. Are there other considerations or options that APRA should take into account? |

Request for submissions

APRA invites written submissions on the key challenges outlined above and potential policy approaches discussed in this paper. Written submissions should be sent to policydevelopment@apra.gov.au by 15 November 2023 and addressed to General Manager, Policy (Policy and Advice Division, APRA). If you would like to meet with APRA, please contact APRA on the address above by 12 October 2023.

Important disclosure notice – publication of submissions

All information in submissions will be made available to the public on the APRA website, unless a respondent expressly requests that all or part of their submission is to remain in confidence. Automatically generated confidentiality statements in emails do not suffice for this purpose. Respondents who would like part of their submission to remain in confidence should provide this information marked as confidential in a separate attachment.

Submissions may be the subject of a request for access made under the Freedom of Information Act 1982 (FOIA). APRA will determine such requests, if any, in accordance with the provisions of the FOIA. Information in the submissions about any APRA-regulated entity that is not in the public domain and that is identified as confidential will be protected by section 56 of the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority Act 1998 and will therefore be exempt from production under the FOIA.