APRA Insight - Issue 3 2018

Testing resilience: The 2017 banking industry stress test

Stress testing plays an important role for both banks and APRA in testing financial resilience and assessing prudential risks. This article provides an overview of APRA’s approach to stress testing, with insights into how APRA developed the 2017 Authorised Deposit-taking Institution (ADI) Industry Stress Test. This builds on the recent speech by APRA Chairman Wayne Byres, Preparing for a rainy day (July 2018), which outlined the results from the 2017 exercise.

Why stress test

The aim of stress testing is, broadly, to test the resilience of financial institutions to adverse conditions, including severe but plausible scenarios that may threaten their viability. The estimation of the impact of adverse scenarios on an entity’s balance sheet provides insights into possible vulnerabilities and supports an assessment of financial resilience. It can be a key input into capital planning and the setting of targets, and in developing potential actions that could be taken to respond and rebuild resilience if needed.

Stress tests are particularly important for the Australian banking system, given the lack of significant prolonged economic stress since the early 1990s. As a forward-looking analytical tool, stress testing can help to improve understanding of the impact of current and emerging risks if a downturn were to occur. Stress tests provide an indication, however, rather than a definitive answer on the impact of adverse conditions, and the results will always reflect the inherent uncertainty that exists in any scenario.

Scenarios – the starting point

The starting point in developing a stress test is to design the scenarios. This is the foundation of the exercise, and it is important that scenarios are calibrated effectively and are well targeted. For industry stress tests, APRA collaborates with both the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) and Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) on the design of scenarios and the economic parameters that define them. In 2017, APRA also engaged with the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) in the design of the operational risk scenario.

Scenarios should be aligned to the purpose of the exercise. At a high level, these are guided within APRA by several objectives – namely to:

- assess system-wide and entity-specific resilience to severe but plausible scenarios;

- improve stress testing capabilities across the industry; and

- support the identification and assessment of core and emerging risks.

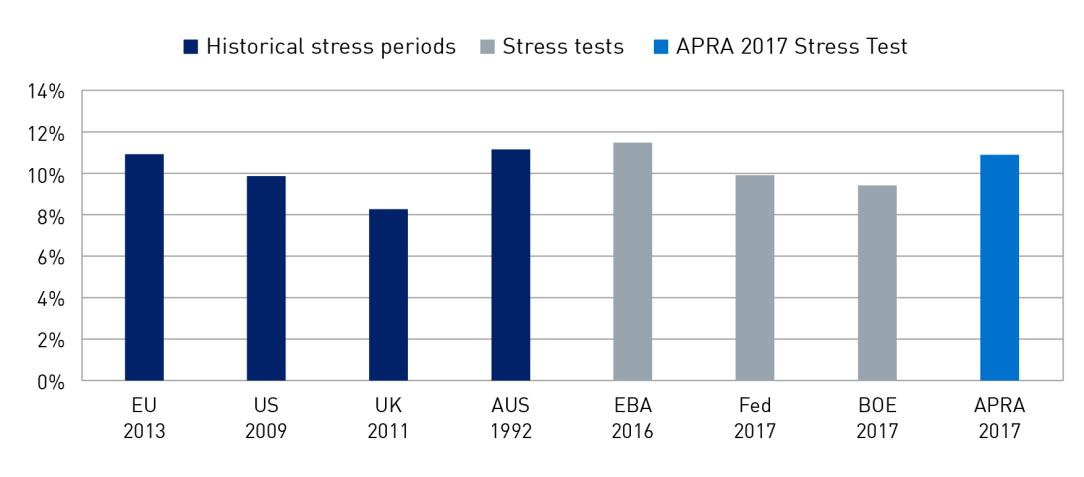

In line with these objectives, APRA developed two scenarios for the 2017 industry stress test. The first was a macroeconomic scenario with a China-led recession in Australia and New Zealand. This was considered the most severe but plausible adverse economic scenario for the banking system at the time.[1] In this scenario, there was assumed to be a fall in Australian GDP of 4 per cent, while house prices declined 35 per cent nationally over three years. The chart below provides an indication of the severity of the scenario: it shows that the assumed peak unemployment rate in the scenario was similar to the 1990s recession in Australia, the United States’ experience in the global financial crisis (GFC), as well as recent overseas regulatory stress tests.

Chart 1: International comparison: Peak unemployment rate

The second scenario involved the same macroeconomic parameters, with an additional operational risk event added. This was designed to test bank resilience beyond traditional economic risks and to consider other vulnerabilities. In this operational risk scenario, APRA asked the participating banks to identify a material operational risk event involving conduct risk and/or mis-selling in the origination of residential mortgages.[2]

The banks chosen for the exercise were selected based primarily on scale, enabling a clear system-wide view to be generated. The 2017 stress test covered 13 of the largest banks with aggregate assets of nearly 90 per cent of the system, as well as the leading lenders mortgage insurers. It included both the major banks and smaller entities that have a significant presence in particular regions or asset classes.

The testing process

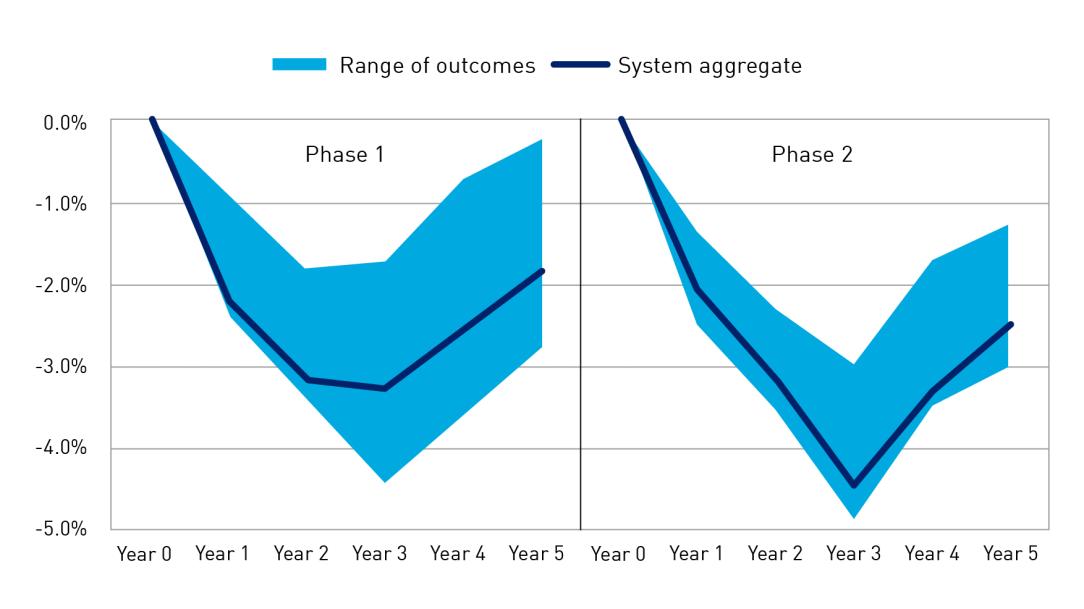

The 2017 stress test was run in two phases. In the first phase, banks generated results using their own stress testing methodologies and models.[3] The results of this phase varied by differences in the risk characteristics of each bank, as well as by how they interpreted and modelled the scenarios.

In the second phase, APRA provided more prescription with specified risk estimates for loan portfolios and other assumptions. This enabled greater comparability across the banks and more consistency in the results. The APRA estimates were developed based on the banks’ results from the first phase, APRA’s own internal modelling, historic and peer stress testing benchmarks, internal and external research and expert judgement.

The estimates were also differentiated based on inherent risk characteristics. For example, riskier interest-only loans were assumed to be more likely to default and losses were estimated to be greater for loans with higher Loan to Valuation Ratios (“LVRs”). For the operational risk scenario, APRA defined key elements and estimates to be applied by the banks, based on research of overseas experience as benchmarks for potential impacts.

Interpreting the results

The table below summarises some key results from the macroeconomic scenario. As important as the quantified outcomes are the lessons learned and implications of the exercise. Stress testing should not be an academic exercise, but should be used to inform assessments of resilience, risks and capacity to respond to stress.

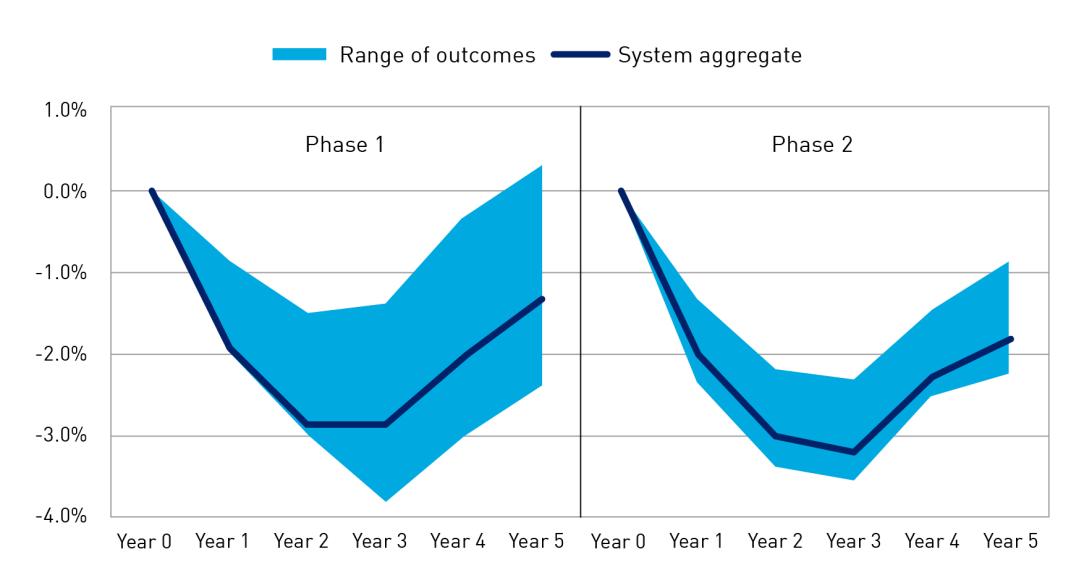

In analysing the results, APRA assessed not only the impact on capital, but also the effects on profitability and loan portfolios. The differences between phase 1 (based on bank’s own modelling) and phase 2 (based on APRA risk estimates) can also shed light on bank stress testing modelling capabilities.

INSERT TABLE

| Macroeconomic scenario - aggregate results | Phase 1 | Phase 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Peak to trough decline in Common Equity Tier 1 capital | -2.87% | -3.21% |

| Peak to trough decline in Return on Equity | -9.86% | -12.05% |

| Peak credit loss rate[4] | 0.81% | 0.90% |

Macroeconomic scenario

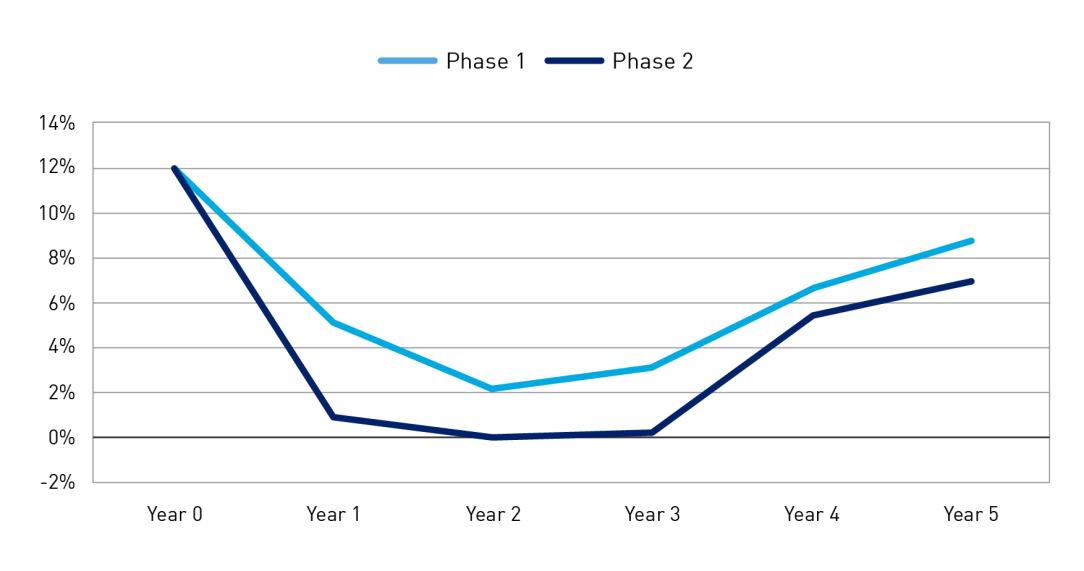

Given the design of the scenario, the impact on the participating banks was material. The results show that in this scenario the decline in profitability was severe and occurred quickly. Return on equity (ROE) in aggregate fell materially in the first two years before recovering after year three. The impact on profitability led to a significant fall in capital in both phases, as shown in Chart 3. There was, however, a wide range in results across banks in both phases.[5]

Chart 2: Aggregate return on equity

Chart 3: Cumulative CET1 impact - Macroeconomic scenario

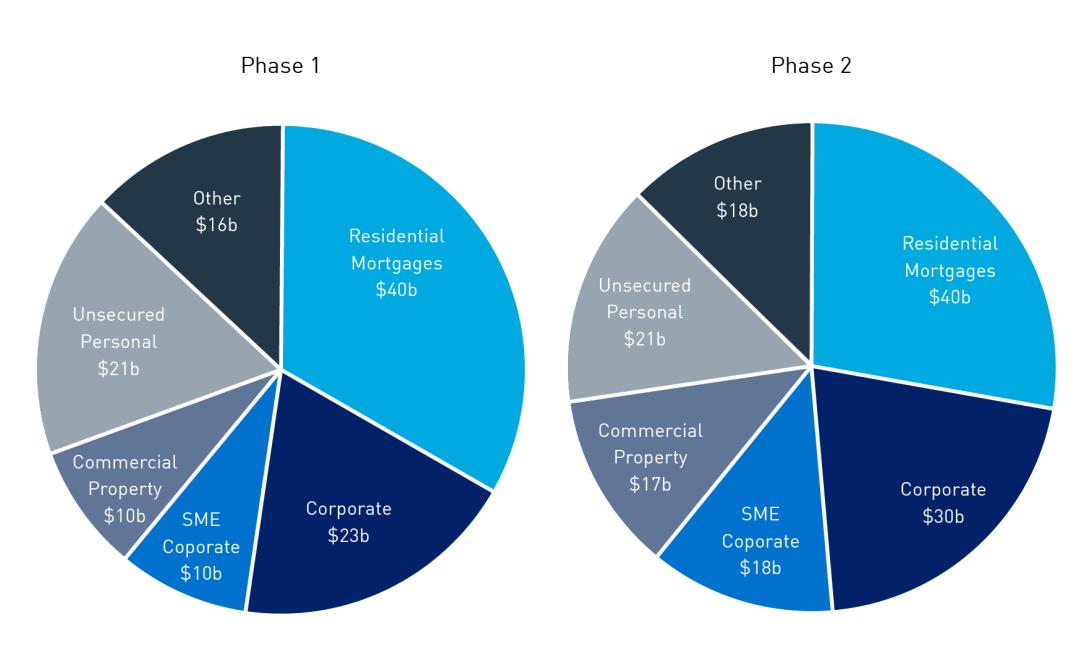

The losses were driven by bad debts in residential mortgage lending, corporate lending and other credit portfolios, as well as lower net interest income and losses on large single counterparties. Across the mortgages portfolios of the banks, aggregate losses were similar in both phases and although the mortgage portfolio contributed the largest aggregate loss, the loss rate was lower than business lending and other consumer lending portfolios.[6] The banks also modelled the impact of the scenario on liquidity and funding positions; most banks were able to maintain their liquidity with a liquidity coverage ratio (LCRs) above 100 per cent (or initiated strategies to restore their LCR within a reasonable timeframe).

Chart 4: Aggregate cumulative credit losses

Operational risk scenario

In the second scenario, the impact of the operational risk event led to a more severe capital outcome, as shown in Chart 5. The operational risk events modelled by the banks in Phase 1 represented a wide range of potential risks, including broker fraud, inappropriate product design and sales practices, inappropriate verification and documentation, overstatement of valuation errors at origination, and serviceability errors. The impact of the operational risk event in Phase 2 based on APRA-defined assumptions was, however, more severe.

Chart 5: Cumulative CET1 impact - Operational risk scenario

Conclusions and lessons learned

Following industry stress test exercises, APRA provides participating entities with formal feedback. In the 2017 stress test, APRA noted the importance of ongoing improvements in modelling capabilities and developing better internal model governance and discussions on results. In practice, a stress event is unlikely to play out exactly as designed and simulated in hypothetical scenarios, reinforcing the need to continue to stress test and enhance stress testing capabilities.

In APRA’s view, the results of the 2017 exercise provide a degree of reassurance: ADIs remained above regulatory minimum levels in what was a very severe stress scenario. In addition, the results were presented before taking into consideration management actions that would likely be taken to rebuild capital and respond to risks in the scenarios.[7] The impact on profitability, loan portfolios and capital would, however, be substantial: this underlines the importance of maintaining strong oversight and prudent risk settings, unquestionably strong capital and ongoing crisis readiness.

Footnotes

- The RBA’s Financial Stability Review in October 2016 highlighted the risks posed by high and rising levels of debt in China, at a time of slowing growth and signs of excess capacity.

- Overseas experience in the GFC has highlighted that operational risk events can impact the financial system alongside an economic downturn. For example, in the US, there was a significant impact from sub-prime mortgage lending, while in the UK, there was additional stress related to the mis-selling of payment protection insurance.

- In order to ensure consistency for the exercise, APRA provided guidance and templates for results.

- This represents the credit loss rate in the most severe year of the stress. Aggregate losses over the duration of the stress period were higher.

- The range presented in the charts is the interquartile range (middle 50 per cent of entities).

- Banks determine credit losses by calculating the likelihood of the loans defaulting (“probability of default”) and then the actual loss on the defaulted loans (“loss given default”) which is then applied to the stressed value of the asset. For mortgages, insurance on higher LVR loans helps to mitigates losses.

- These actions include raising equity, loan repricing, cost cutting, tightening lending standards and balance sheet measures. Within this set, the cornerstone action was typically equity raisings, as a relatively quick step. In the operational risk scenario, the participating banks raised around $40bn in equity, almost twice the level as during the GFC. The assumption that banks were last to market challenged thinking around the potential capacity and pricing implications.

Cloud control: APRA evolves its stance on shared computing services

The advent and development of cloud computing technology over the past decade has had a profound impact on the financial services sector, both in Australia and globally. The availability of elastic, cost-effective, virtually limitless computer processing, network and data storage has allowed organisations of all sizes and levels of sophistication to offer financial services without the need to purchase and maintain costly infrastructure and support staff. APRA–regulated entities were quick to embrace the cloud, and usage of the technology continues to grow.

Though cloud offers the potential for substantial benefits and opportunities, it also presents significant risks that APRA-regulated entities must manage in the interests of prudential safety. With that in mind, APRA released an information paper in 2015 on the use of cloud computing. The paper expressed scepticism about the ability of entities to safely use the cloud for functions involving heightened inherent risk.

In the three years since, there has been continuous evolution of both cloud computing service offerings and APRA-regulated entities’ risk management. APRA recognises that, generally, cloud service providers have strengthened their control environments, increased transparency regarding the nature of the controls in place and improved their customers’ ability to monitor their environments. APRA-regulated entities have also improved their management capability and processes for assessing and overseeing the cloud services provided.

On that basis, APRA released in late September an updated information paper on cloud computing, expressing a more open stance on cloud usage by APRA-regulated entities. The update reflects APRA’s observation of the growing use of cloud computing services by APRA-regulated entities, an increasing appetite to do so for higher risk activities, as well as areas of weakness identified as part of APRA’s supervisory activities that entities are expected to address as they consider increased cloud usage.

Risks must be understood and managed

Cloud computing services are used for a variety of functions by APRA-regulated entities. Depending on the function, disruption of a cloud service (including a compromise of confidentiality, integrity or availability of systems or data) could have material consequences for the entity or its customers. The various services offered through the cloud present differing risk profiles, with each cloud provider offering numerous options with varying technologies, controls and responsibility models. These factors add greater layers of complexity and, potentially, a lack of clarity with respect to responsibility, which can challenge effective risk management.

APRA has classified the inherent risk of cloud computing services into three broad categories: low, heightened and extreme.

- For arrangements with low inherent risk (and not involving off-shoring), APRA would not expect an APRA-regulated entity to consult APRA prior to entering into the arrangement.

- For arrangements with heightened risk, APRA would expect to be consulted after the APRA-regulated entity’s internal governance process is completed.

- For arrangements involving extreme inherent risk, APRA encourages early engagement, and will subject these arrangements to a higher level of scrutiny. APRA expects all risks to be managed appropriately, commensurate with their inherent risk. However, for extreme inherent risk, APRA expects an entity will be able to demonstrate to APRA’s satisfaction, prior to entering into the arrangement, that the entity understands the risks associated with the arrangement, and that the entity’s risk management and risk mitigation techniques are sufficiently strong.

| Under CPS 231 Outsourcing, APRA-regulated entities must demonstrate the following: |

|---|

| Ability to continue operations and meet obligations following a loss of service and a range of other disruption scenarios. |

| Preservation of the quality (including security) of both critical and sensitive data. |

| Compliance with legislative and prudential requirements. |

Absence of jurisdictional, contractual or technical considerations that may inhibit APRA’s ability to fulfil its duties as prudential regulator, including impediments to timely access to documentation and data/information.

| Risk management area | Key message |

|---|---|

| Strategy | Strategies should be defined and supported by a clearly articulated architectural roadmap. Strategies should align with the broader business and technology strategies, and include consideration of organisational change and required capability to manage and operate the arrangements. |

| Governance | The APRA-regulated entity’s board, governance committee or other appropriate governance authorities should be informed of material cloud initiatives and be able to form a view as to the adequacy of the risk and control frameworks to manage the arrangement in line with the board risk appetite. |

| Solution selection process | The process for selecting the IT solution (including related software programs and related services) should be systematic, considered and comply with established processes for changing the IT environment. This includes a comprehensive due diligence process to verify the maturity, adequacy and appropriateness of the cloud provider and services selected (including the associated control environment), taking into account the intended usage of the cloud computing service. |

| APRA access and ability to act | An APRA access clause must be included in the cloud provider agreement. This includes access to documentation and information, and the right for APRA to conduct onsite visits of the cloud provider. |

| Transition approach | A cautious and measured approach should be adopted for transitioning to a cloud computing service, particularly where risks are heightened. |

| Risk assessments and security | Entities are expected to conduct comprehensive security and risk assessments of all material cloud arrangements, initially and periodically, and on material change. Controls should be commensurate with the risks involved. |

| Implementation of controls | The implementation of controls by the cloud service provider and the APRA-regulated entity should reflect the entity’s and service provider’s differing levels of responsibility for operating and managing the various cloud arrangements. |

| Ongoing oversight | Entities should develop and maintain ongoing operational and strategic oversight mechanisms that facilitate assessment of performance against agreed service levels, assessment of the ongoing viability of the cloud provider and the service, timely notification of key changes and a timely response to issues and emerging risks. |

| Business disruption | APRA expects that an APRA-regulated entity would continue to meet its obligations regardless of disruptions resulting from a failure of technology, people, processes or cloud provider. |

| Internal audit | Entities should provide assurance to the board that material arrangements are appropriately managed, and that the service provision management framework is effective. This includes assessing the assurance provided from audits initiated by the service provider. |

Common areas of responsibility for the different cloud computing models

| Areas of responsibility | Infrastructure as a Service | Platform as a Service | Software as a Service |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ongoing monitoring for control effectiveness | Customer | Customer | Customer |

| Customer-side information security* | Customer | Customer | Customer |

| Data quality | Customer | Customer | Customer |

| Application management | Customer | Customer | Provider |

| Virtual machines and networks | Customer | Provider | Provider |

| Cloud infrastructure** | Provider | Provider | Provider |

* This includes customer side: user identity and access, interface control, vulnerability and threat management, maintenance of IT asset currency, incident detection and response, configuration management, encryption and key management.

** This includes: data centres, servers, networks, cloud fabric, customer access as well as information security controls such as vulnerability and threat management, incident detection, response and client notification.

Conclusion

The use of cloud computing services represents a significant change to the way technology is employed, and APRA expects cloud usage by its regulated entities will continue to grow. While cloud computing can bring benefits, it also brings associated risks which must be understood and managed effectively if APRA-regulated entities wish to take advantage of this service.

APRA will seek to ensure that regulated entities’ risk management and mitigation techniques are commensurate with their usage of cloud computing services. Consequently, APRA encourages regulated entities that are contemplating using cloud solutions which involve heightened and extreme inherent risks to consult APRA prior to entering into any formal arrangement with a cloud provider.

The private health insurance policy roadmap: Where are we now?

Private health insurers face a dynamic and challenging landscape, characterised by affordability issues and shifting consumer behaviour, evolving community expectations of insurer conduct, changing operational requirements and cyber risks. Private health insurers need the ability to respond to these challenges in strategic and innovative ways to remain sustainable.

Affordability is currently attracting a lot of media attention, as health insurance premiums continue to increase by more than inflation and average weekly earnings, while the private health insurance rebate is declining. The result is that many people are downgrading or not renewing their insurance cover. The percentage of the population covered by private health insurance has fallen from 47 per cent to 45 per cent over the last three years. A large proportion of this reduction has been among the younger, healthier cohort, who are vital to support a community-rated system. As the proportion of younger members declines, premiums will need to increase to make up for the shortfall – potentially exacerbating the issue.

Furthering APRA’s concern is that the data points to the trends around affordability worsening. Some industry stakeholders consider the industry is approaching a ‘tipping-point’, and the prospect of a shrinking, ageing and less healthy population of health insurance policyholders raises questions about the industry’s long-term sustainability. Some insurers have sought to provide leadership in addressing these challenges, but more needs to be done.

APRA’s role as the prudential regulator of private health insurance is to implement measures designed to keep the industry on a sustainable footing. APRA is working to build private health insurer resilience across three key dimensions - risk, governance and capital - and has been doing this in phases.

Phase 1 was completed in 2017 with the extension of APRA’s cross-industry risk management prudential standard to private health insurers.

The PHI Phase 2 governance review was launched in February 2018 to enhance governance, and business planning processes within the industry. The measures were outlined in APRA’s consultation package, titled Governance, fit and proper, audit and disclosure requirements for private health insurers. Submissions were broadly supportive of the package, but did raise four issues for further consideration: director tenure; frequency of audit reports; auditor experience and auditor rotation requirements.

After careful consideration of the submissions, and drawing on APRA’s experience in other sectors, APRA formed the view that the proposals made were appropriate and accordingly no substantive changes were made in the final versions. On the question of APRA’s guidance on director tenure in particular, APRA considers that an increased focus on board renewal and succession planning is critical to enable boards to remain open to new thinking and provide robust oversight.

APRA has now released the following prudential standards and guidance for private health insurers:

- Cross industry Prudential Standard CPS 510 Governance (CPS 510), which replaces the private health insurance-specific standard, HPS 510 Governance. CPS 510 aims to foster boards equipped to anticipate, understand and manage the changing environment and shifting consumer expectations;

- Prudential Standard CPS 520 Fit and Proper (CPS 520), is new to the sector. It requires boards to establish and apply a written policy to ensure the competence and integrity of anyone exercising material influence over the company;

- Prudential Standard HPS 310 Audit and Related Matters (HPS 310), recognises the important role external auditors can play in improving data integrity and prudential compliance;

- Prudential Standard HPS 001 Definitions (HPS 001) includes the new terminology in the standards; and

- Prudential Practice Guide HPG 510 Governance (HPG 510) and Prudential Practice Guide HPG 520 Fit and Proper set out APRA’s expectations of the requirements in the standards.

These changes are designed to equip private health insurers to respond to major challenges, such as affordability, by fostering boards that remain open to change and recognise the strategic context of their decision-making. The strengthened prudential framework will also require responsible persons to have the appropriate skills and knowledge to effectively implement those decisions.

As insurers implement the new requirements, APRA does not want to cause a disorderly transition. Some measures, such as director tenure and the auditor rotation requirements, may require additional transition arrangements in order to facilitate the desired change in an orderly way. This will be addressed through case-by-case discussions between private health insurers and supervisors, where insurers can make a strong case to APRA for different approaches. APRA encourages early engagement by insurers on these matters with their supervisor.

The next step

APRA’s attention will now turn to reviewing the private health insurance capital standards, under Phase 3 of the private health insurance policy roadmap. APRA does not start this process with a view that capital levels in the industry are too high, or that they should be reduced, but notes the crucial role that strong capital levels play in supporting insurer resilience. Through the review process, APRA will consider whether the private health insurance framework should be more closely aligned with the capital framework for the general and life insurance sectors. APRA will engage further with private health insurers later this year and will consult extensively with stakeholders to determine the extent of any industry-specific factors that warrant an alternative approach.

Conclusion

To remain fit for purpose in an increasingly challenging environment, private health insurers will need to lift the bar in their approaches to risk management and governance. The reforms to the prudential framework undertaken by APRA provide a sound starting point, but to realise the full benefits, insurers themselves will need to robustly implement the changes and embed them in their operations. APRA considers this fortification of the three areas of risk management, governance and capital to be a valuable investment in the long-term sustainability of the sector.