APRA Insight - Issue 2 2017

From fund performance to member outcomes: Assessing the superannuation industry

As the superannuation industry evolves, so too must the approach to assessing how RSE licensees are performing. In particular, there must be an adequate focus on assessing the delivery of quality outcomes to fund members (and other beneficiaries), as that is fundamental to an RSE licensee meeting its ongoing duty to act in the best interests of beneficiaries. The delivery of quality outcomes is driven, to varying degrees, by better governance practices, improved competition and efficiency in the industry, greater transparency and a continued focus on the delivery of quality, value for money products and services.

The shifting landscape

The superannuation industry has undergone, and will continue to experience, significant change, including structural and regulatory changes. Whilst the MySuper framework has simplified the default product market to some extent, the superannuation industry and range of products offered have become more complex and, as a result, less comparable.

Public offer funds commonly offer a range of investment options in addition to their default MySuper option, even if the default option dominates the assets held in the fund. These options include accumulation and decumulation (i.e. pension/retirement income) options, which have very different purposes and different tax treatment. They also include options with wide differences in risk/return objectives to suit the varying needs and preferences of fund members, in part reflecting varying demographic characteristics. Over the last ten years, the industry has seen a significantly reduced number of RSEs (from 638 APRA-regulated RSEs with more than four members in 2006 to 225 in 2016) offering a substantially increased (and increasing) number of investment options (from around 14,000 in 2004 to 45,000 in 2016).

These changes mean that it is critically important to understand the operation and performance of the wide range of underlying products and options within superannuation funds that ultimately provide members with retirement outcomes.

The Stronger Super reforms in 2013, including the introduction of MySuper products and the changes to APRA’s data collection for superannuation, have afforded RSE licensees, industry commentators and APRA the opportunity to better assess industry performance based on more detailed, comparable and hence ultimately more meaningful information about the experience of fund members than was previously available. However, there remains further room for improvement in this regard, as APRA had deferred collection of detailed investment performance data on non-MySuper investment options pending finalisation of product dashboard requirements for choice products.

Rethinking fund-level performance

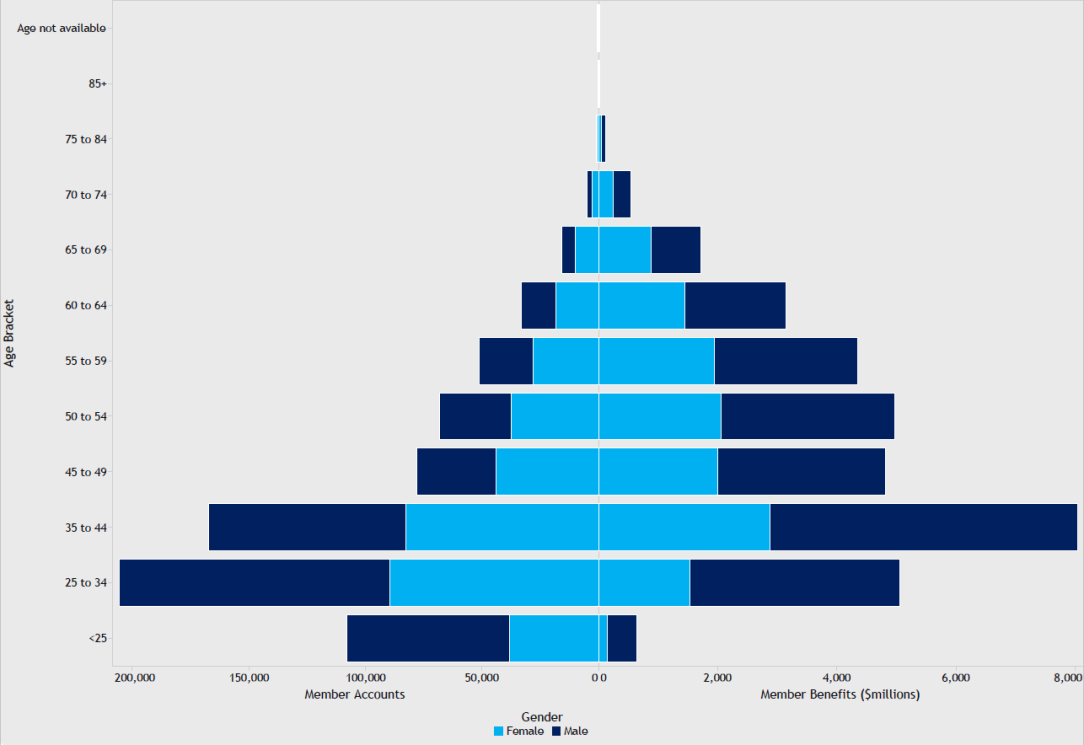

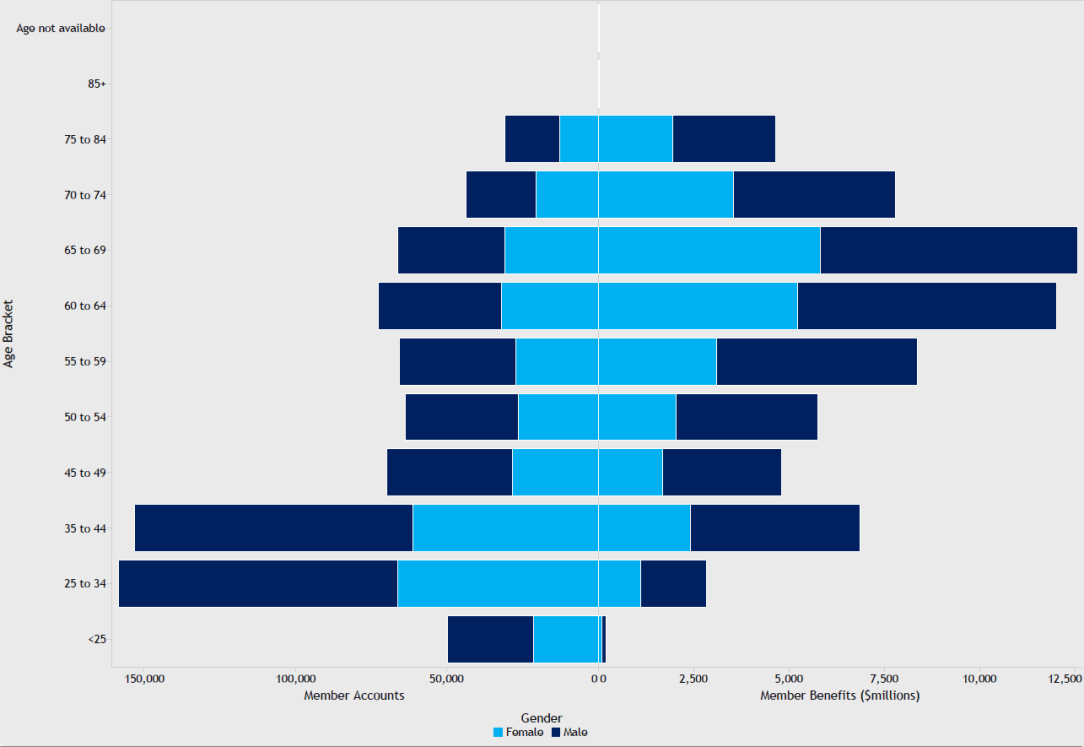

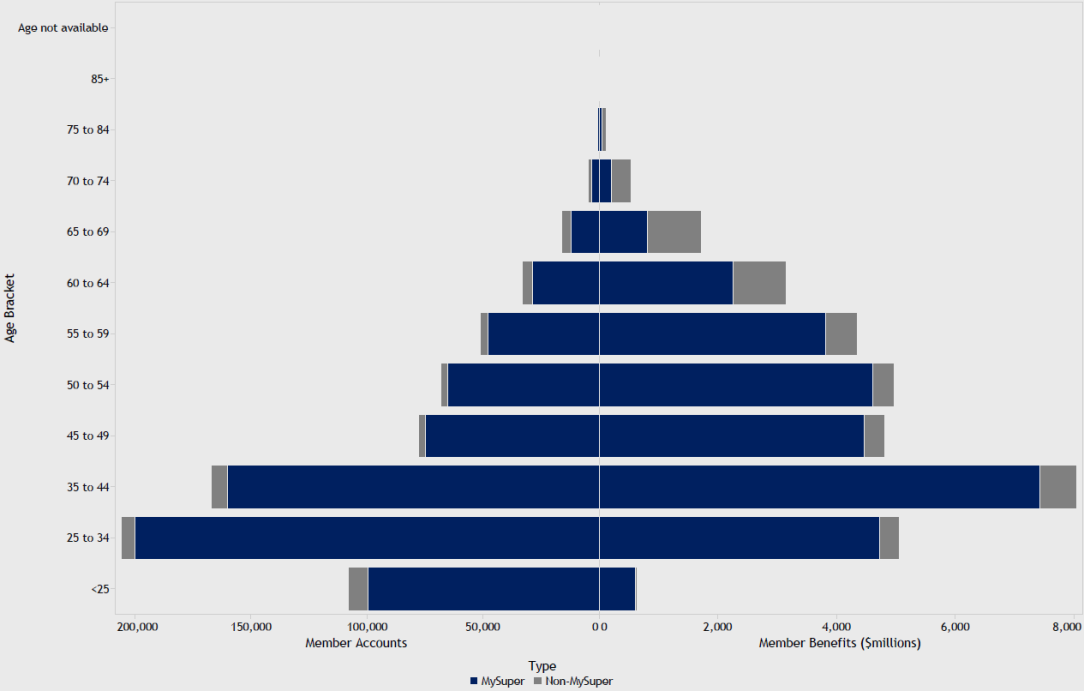

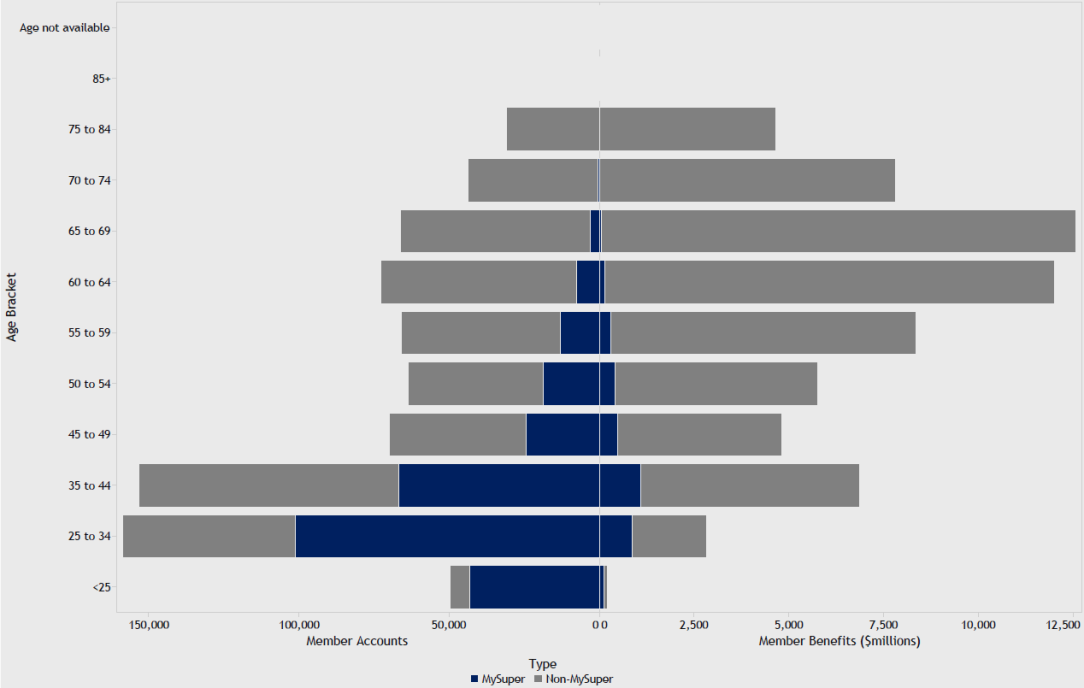

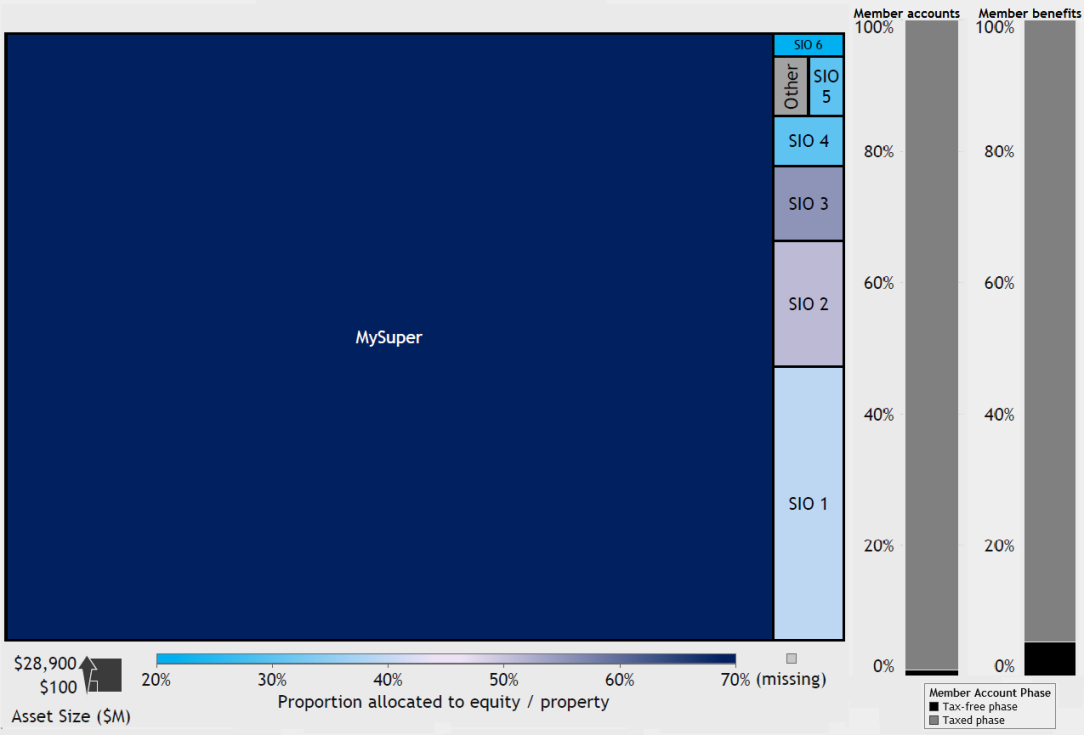

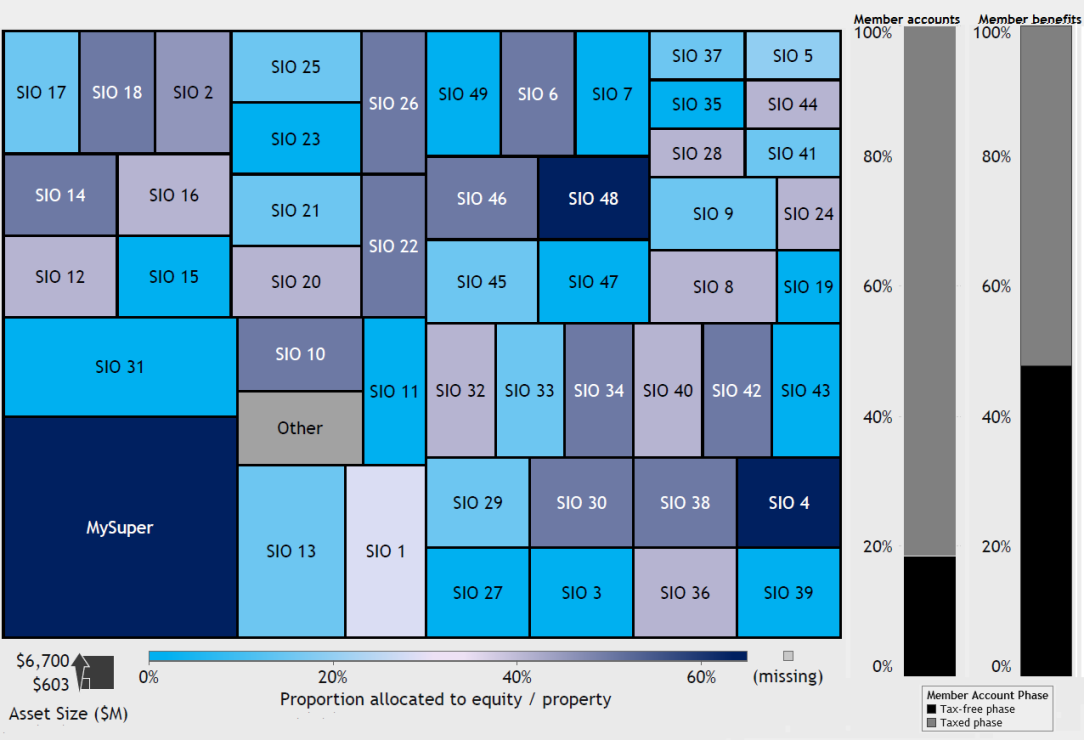

APRA has, since 2009, published a time series of the fund level rate of return (RoR), which provides some information about RSE level performance. However, RSE structures differ significantly, reflecting a number of factors including underlying demographic differences and the proportion of assets held in MySuper vs choice investment options, as illustrated in figures 1 and 2 below1.

Figure 1: Fund A member accounts/benefits by gender

Figure 1: Fund B member accounts/benefits by gender

Figure 2: Fund A Member accounts/benefits by MySuper vs choice products

Figure 2: Fund B Member accounts/benefits by MySuper vs choice products

This wide variance in RSE structures is why APRA continues to emphasise that the RoR should not, on its own, be used to assess the performance of an RSE licensee.

Fund level RoR is not reflective of the outcomes achieved for members as it does not accurately reflect the variation in cash flows and asset values that occurs within the fund. Within most RSEs, members participate in one or more different products. That means that assets generating earnings at the RSE level are the combination of assets held for MySuper products, choice investment products, pension products and also for fund reserves. These different segments typically have very different investment strategies, and hence asset allocations, that reflect their different purposes and risk/return targets. They are also likely to have different fees and costs. This significantly diminishes the utility of the RoR calculation for assessing the quality of outcomes for members, and hence whether or not an RSE licensee is meeting its ongoing duty to act in the best interests of beneficiaries.

Figure 3 compares RSE structures with a different mix of assets underlying MySuper and choice products. The figure illustrates the relative size of various investment options within each RSE, the relative underlying differences in the allocation to equity and property investments for each option and the proportion of assets that relate to pension accounts. This relatively simple comparison highlights the range of options with different return objectives, risk profiles, and liquidity requirements that there may be within an RSE.

Figure 3: Fund A Structure: Example RSE structures (MySuper and select investment options)

Figure 3: Fund B Structure: Example RSE structures (MySuper and select investment options)

The RoR calculation approximates the rate at which an RSE generates earnings on its net assets2. The calculation assumes that all cash flows occur half way through a given year, meaning it can be sensitive to the timing and size of cash flows. The RoR may not, therefore, accurately reflect RSE performance when cash flows are not evenly distributed over the year (as may occur, for example, due to significant payments into or out of the fund as a result of successor fund transfers or transfers of accrued default amounts between funds or products).

Calculating investment performance for a portfolio of diverse assets is complex, and requires accurate measurement of the market value of each asset. Using quarterly or monthly crediting rates to value portfolios was a reasonable approach when contributions or withdrawals were processed less frequently. The move to unit pricing almost universally across the superannuation sector, however, enables daily valuation – this allows the investment performance of individual investment options to be more accurately measured and compared. APRA now collects from RSE licensees and publishes this more accurate measure of investment performance over a quarter (the net investment return) for MySuper products, which better reflects the return earned for members of these products.

Assessing quality outcomes

The assessment of whether a product is delivering quality outcomes for members needs to look at both qualitative and quantitative aspects. It is not just investment performance and fees or costs that should be considered, but also the nature and quality of the benefits and services being provided and the adequacy of the RSE licensee’s governance and risk management frameworks and practices. APRA also expects all RSE licensees to assess the sustainability of their products over the medium to long term. This is particularly important for MySuper products given the potential adverse impact on remaining default members of, for example, declining membership or ongoing negative cash flows with consequent potential impacts on investment strategy and costs.

APRA expects RSE licensees, when assessing the outcomes for members of their products, to consider outcomes primarily based on performance against pre-established targets or objectives. Establishing appropriate targets would include comparison against relevant benchmarks and, where like-for-like comparisons are possible, against peer offerings.

When considering MySuper products, peer comparison is more straightforward than was the case previously for default products as, by their very design and structure, they are intended to be more comparable. There is now (at least) three years of MySuper product data available to support like-for-like assessment of outcomes for these products.

APRA expects that when assessing the extent to which products deliver quality member outcomes, RSE licensees will consider a range of metrics, drawn from both data reported to APRA and information that is available more broadly, including:

- net returns, on an absolute basis and relative to risk/return targets;

- fees and costs; and

- the level and cost of insurance.

- As a supplement to information RSE licensees will have within their businesses, APRA’s published data also provides valuable input for a forward-looking assessment across all products offered by RSE licensees, including:

- net outflow ratios;

- trends in assets and membership; and

- active member ratios.

Using metrics such as those noted above, and others as relevant, APRA has identified a cohort of MySuper products that appear to be providing relatively poor outcomes across most, if not all, of the metrics considered relevant to assessing member outcomes and future sustainability. APRA’s attention is not limited to MySuper products; similar analysis is being undertaken for choice products in the accumulation and pension phases.

APRA’s quantitative assessment is supplemented with supervisory consideration of product characteristics and the strategic and business planning practices of RSE licensees. This includes, for example, consideration of the effectiveness of RSE-level strategies, and the investment strategies for each option/product, in seeking to ensure that the number of investment options and products offered does not lead to unnecessary complexity or inappropriate outcomes for members.

For the cohort of products that has been identified, APRA will initially meet with the board of the RSE licensee to discuss our assessment. These RSE licensees will be required to develop a credible strategy to address the identified shortcomings within a reasonably short period, and to engage more regularly with APRA as part of monitoring progress in implementing that strategy. APRA expects, where it is clear that a product cannot continue to operate in the best interest of its members, RSE licensees will act to ensure a timely and well-managed transfer of the members to another suitable product – which may be within their own operations or provided by another RSE licensee. In some cases this may ultimately lead to the exit of the RSE licensee from the industry.

As part of its ongoing supervision activities, APRA will also be discussing the approach to assessing member outcomes and future sustainability with all RSE licensees.

Upcoming activities

APRA will soon write to the superannuation industry to explain in more depth the assessment process being undertaken as outlined above. The letter will explain how APRA is using each of the metrics to form an assessment of the quality of member outcomes and future sustainability. APRA encourages all RSE licensees to consider this approach, and available information, when assessing the performance and outcomes for their products, with a view to identifying areas of focus for remediation or improvement.

APRA also intends to undertake a post-implementation review of APRA’s implementation of the Stronger Super reforms, including the prudential and reporting frameworks. This will include consideration of the information needed, for choice and pension products in particular, to better support APRA’s supervision and also broader consideration of outcomes for members by RSE licensees and other stakeholders.

1 The figures represent RSE structures that are not uncommon for funds identifying as industry funds and retail funds (Fund A and Fund B respectively).

2 RoR is calculated as net earnings after tax divided by cash flow adjusted net assets. Five and ten year RoRs are calculated as the geometric average of the most recent five and ten year periods. Cash flow adjusted net assets is the sum of net assets at the beginning of the period and half of net flows.

Resolution planning

APRA meets its objectives1 as a prudential regulator through its three core functions: supervision, policy and resolution. The resolution function involves protecting beneficiary interests by ensuring APRA would be able to respond promptly and effectively to manage a failure or crisis in the financial system.

A key lesson from the global financial crisis was that an effective resolution function requires an advanced level of preparedness through contingency planning before a failure or crisis event materialises. ‘Resolution planning’ refers to the process by which APRA works with a regulated institution to develop a plan for how APRA would use its powers to manage the failure of that institution. Resolution planning also includes taking steps, ahead of time, to remove potential barriers to an orderly and effective resolution.

Within the legislative framework in Australia, APRA has a range of statutory powers through which it could intervene to manage a failure or crisis event. In addition, reforms currently being progressed by the Government are expected to broaden and strengthen the scope of these powers, as well as clarify the role of resolution planning in prudential supervision2. This article provides context for these reforms and explains APRA’s current initiatives to develop and enhance its framework for resolution planning.

The importance of planning for failure

APRA does not operate a zero failure prudential regime; to do so would not be optimal as it would require severe limitations to be placed on the risk-taking abilities of APRA-regulated industries and the financial system3. Prudential supervision cannot provide a guarantee against the failure of a regulated institution occurring from time to time and, provided the exits can be managed in an orderly way, such failures should be seen as part of the normal market dynamics of a competitive system.

In this context, if a regulated institution is failing or likely to fail, APRA’s aim will be to minimise losses to beneficiaries, and disruption to the broader financial system, by managing an orderly exit of the institution. By contrast, a disorderly failure would be one in which there is material disruption to the critical economic functions and services that a failed institution provides, resulting in significant impacts on beneficiaries, the financial system and the wider economy.

Given the interconnectedness of financial institutions, and potential for contagion within the financial system, planning for failure is integral to achieving orderly exits. APRA therefore continues to strengthen its focus on crisis planning as part of its supervisory framework. This includes through supervisory review of the recovery plans of regulated institutions (see further below), and through the ongoing assessment of the resolvability of institutions.

APRA’s supervisory philosophy is built on the premise that the primary responsibility for the prudent management of a regulated institution rests with its board and management4. Consistent with this, a key component of crisis preparedness will be the institution’s own recovery plan, which focuses on the actions it can take to respond to a significant stress and restore itself to a financially sound position. APRA recently concluded a review and benchmarking exercise of the recovery plans of large and medium ADIs, and a similar review is planned to commence with large and medium insurers this year5. The existence of strong recovery planning practices should lessen the likelihood that APRA would have to intervene to use its powers to resolve an institution in financial difficulty.

In addition, the Financial Claims Schemes for authorised deposit-taking institutions (ADIs) and general insurers provide an important safety net, which gives confidence to certain beneficiaries that their interests will be protected in the event of a failure or crisis6.

However, for those institutions which provide functions that might be critical in nature, APRA will also require a resolution plan to be developed. ‘Critical functions’7 are those functions provided by an institution, where the sudden failure to provide the function would be likely to have a material impact on financial stability and third parties, give rise to contagion to other financial institutions or undermine the general confidence of market participants. Effective resolution planning aims to avoid disorderly failure by providing a blueprint for APRA to intervene to safeguard an institution’s critical functions during a period of resolution.

Assessing and improving resolvability

The failure or disorderly wind down of a critical function could have a wide range of impacts. In summary, these can be classified as (i) direct impacts on customers and (ii) contagion impacts to the wider financial system or broader economy. Customer impacts could be particularly heightened where a function is provided to certain customer types, such as retail or SME customers, or where an institution provides a particular function for which appropriate and timely alternatives are not available8. An example of contagion impacts could be the failure of a payments or settlement function that affects market liquidity and confidence, leading to systemic impact through interconnections to other financial institutions, third parties and markets.

In developing a viable resolution plan for an institution, APRA needs to consider how it would use its powers to stabilise critical functions in order to minimise the adverse impacts. Therefore, the resolution planning process will involve working closely with the relevant institution to:

- determine what (if any) critical functions the institution might provide;

- map the relevant functions to the institution’s group structure and identify key intra-group dependencies, such as critical shared services on which the functions are reliant;

- use this information to assess the current resolvability of the institution, based on a preferred resolution strategy identified by APRA;

- identify potential barriers to resolution, such as operational complexities or inadequate financial capacity to support the continuation of critical functions;

- agree the steps and timeframes for removing barriers in order to improve the institution’s resolvability; and

- reflect the preferred resolution strategy in an operational plan.

APRA needs to work closely with institutions in the development of resolution plans. Plans will not be ‘set and forget’ but rather are likely to involve an iterative process of improving resolvability over time. In particular, institutions need to provide relevant data and be closely involved in reflecting resolution strategies in operational plans. The process for identifying and removing barriers to resolution must also be a collaborative one, with due account given to the relative costs / benefits and other consequences of the potential prepositioning measures which could be taken.

Conclusion

APRA wishes to avoid the disorderly failure of a regulated institution wherever possible. Planning for failure - from both an industry and regulatory perspective - will continue to be a key area of strategic focus for APRA. Recovery planning is an important component of crisis preparedness and supervisors will expect to see continued improvement in the credibility of institutions’ recovery plans in the near term.

The development of a credible framework for resolution planning is an important strategic initiative for APRA, and will involve working closely with relevant institutions over the next few years. In line with proposed reforms to APRA’s crisis management powers, APRA intends that these requirements will in due course be more formally reflected in the prudential framework.

1 APRA’s strategic plan outlines its objectives which include protecting beneficiary interests and promoting financial stability in Australia. Beneficiaries in this context refers to those creditors of a regulated institution that APRA is tasked with protecting: ADI depositors, insurance policyholders and superannuation fund members.

2 Refer to recommendation 5 of the Financial System Inquiry, Final Report

3 See Byres W (August 2016), ‘Finding success in failure’, speech given at the Actuaries Institute Banking Conference.

4 Pursuant to CPS/SPS 220 Risk Management.

5 In due course, APRA expects that all APRA-regulated institutions will have a recovery plan, or equivalent contingency plan, which is proportionate to their size and complexity. Further information on recovery planning will be made available through supervisory teams.

6 The FCS seeks to provide certain beneficiaries with prompt access to their funds: up to $250,000 per account holder at each bank, building society or credit union; most claims up to $5,000 in relation to general insurers, with claims above $5,000 also covered for eligible policyholders and certain third parties. For further details on how the FCS works, please refer to the FCS page.

7 See the Financial Stability Board’s ‘Guidance on identification of critical functions and critical shared services’.

8 An example of such a critical function would be the builders’ warranty insurance provided by HIH Insurance Limited at the time of its failure, the sudden withdrawal of which caused significant systemic impacts.

APRA and ASIC life insurance claims data collection project

APRA and the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) are jointly undertaking a project to collect data on life insurance claims, which arose in the context of growing community concern about the handling and payment of claims across the life insurance industry.

The objectives of this work are to improve the accountability and performance of life insurers, and facilitate an informed public discussion about the value of insurance and performance of the life insurance industry by collecting and publishing credible, reliable and comparable data. The intention is for this data to be collected and published on an entity-level basis, with sufficient detail to allow meaningful comparisons of insurer performance, and with sufficient context to effectively inform consumers and other stakeholders.

In May 2017, APRA released a discussion paper1 outlining in detail the objectives and approach for the data collection.

Consumer sentiment

Life insurance supports many consumers in their time of need but consumer trust in the industry has been undermined. In 2016, ASIC conducted a review of claims handling across the life insurance industry and released Report 498 Life insurance claims: An industry review2 last October.

The review established that ‘overall, where a decision has been made, 90 per cent of claims are paid in the first instance’, but that at present ‘it is very difficult for consumers and other stakeholders to assess the claims outcomes and performance of the life insurance sector, including trends over time.’ This undermines insurer accountability and consumer trust.

Furthermore, the review found ‘a clear need for better quality, more consistent and more transparent data about insurance claims’. It noted that claims handling performance metrics varied significantly between insurers, and recommended a 'consistent public reporting regime for claims data and claims outcomes, including claims handling timeframes and dispute levels across all policy types'.

A recent PWC survey found that ‘while 78 per cent of Australians view life insurance as important, only 42 per cent believe their life insurer will be there for them in their time of need’3. There is a trust gap and it needs to be improved.

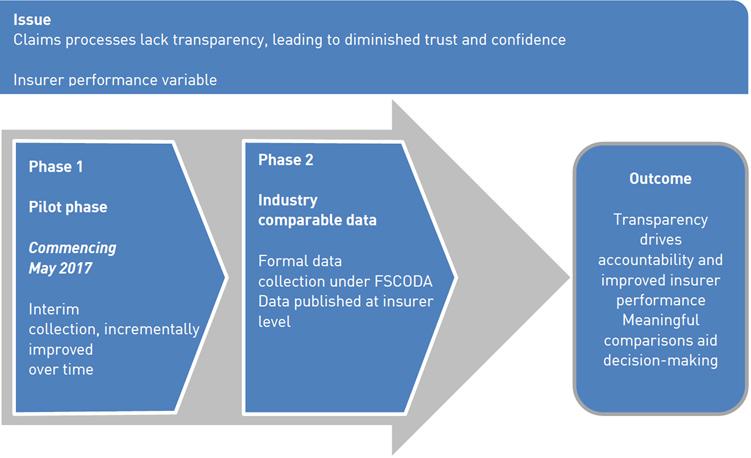

Collection phase

The collection will occur in two phases. The first was launched in May 2017 and will serve as a pilot for the data template and definitions. The pilot phase will continue, while insurers go through the process of aligning their data to the new definitions. The data template and definitions will be iteratively refined, in light of analysis of the data collected and feedback from stakeholders.

In this phase, life insurers that write death, total and permanent disability, trauma and/or income protection/group salary continuance have been requested to complete a reporting template according to specified instructions. The first round of data will cover the 2016 calendar year, and completed templates were required by 30 June 2017. The agencies are aware that many insurers will have difficulty completing all aspects of the template according to the instructions, and that for many, manual workarounds to provide the requested data will be needed. To allow time for necessary improvements to be made, data can be provided on a best endeavours basis in phase one.

Figure 1: Phases of the consultation process

The agencies are collecting data in three key areas:

- Policy data on the in-force numbers of policies, in-force premium income and in-force sums insured;

- Claims data which will include detailed information on the claims received, how they were handled by the insurer, as well as associated claims processing durations; and

- Dispute data in respect of those claims which are subject to an internal and/or external dispute resolution process, as well as litigated disputes

The data collected will cover a number of key dimensions, including cover types and distribution types, and can be used to generate metrics such as claims admittance/decline rates, claims and disputes processing durations and dispute ratios. No entity-level data will be published in phase one.

In the second phase, a formal, legally enforceable reporting collection will be developed drawing on the experience with the pilot exercise under phase 1. It will follow a similar approach to other collections administered by APRA, with reporting standards under the Financial Sector Collection of Data Act 2001 (FSCODA). For clarity, each reporting standard will include reporting forms with clearly defined instructions, as well as specified reporting periods, due dates and data quality arrangements. In addition, it will utilise APRA’s existing data submission processes, including data quality checks.

Publication phases

A further part of the second phase will be the development of publications to support the objectives of this project. APRA expects different users to have different expectations of the content of the publications. What is useful and meaningful for consumers may differ significantly from what, for example, market analysts may be looking for. Publications will need to be carefully designed to recognise and balance these varying needs and priorities. The agencies will consult on the design of publications as they are being developed.

There are two distinct ways of presenting the data:

- An industry-level publication providing data on an aggregate basis, which gives the reader a broad overview of the performance of the Life Insurance industry.

- An entity-level publication providing data on an insurer-by-insurer basis, which provides an understanding of how individual insurers are performing. This approach is also consistent with ASIC's use of data to analyse emerging risks and potential consumer harm.

Importantly, although the data is primarily being collected for publication, not all data that is collected will necessarily be published. ASIC and APRA may use some of it for their own analysis.

Confidentiality

Under section 56 of the APRA Act, data submitted to APRA under FSCODA is protected information. The section 56 protection applies to all data submitted to APRA under both Phase 1 and Phase 2. APRA can release data to ASIC, as necessary to achieve the objectives of this collection, but the data will continue to be protected information under section 56.

APRA is generally able to publish aggregate industry-level data without restriction. In keeping with its intention to improve accountability of the industry and inform public discussion about the performance of the life insurance industry, however, it will ultimately be necessary to publish data at an entity level as well. To support entity-level publication, APRA will consult on determining certain data to be non-confidential, taking into account the benefit to the public from the disclosure of the data and any detriment to commercial interests that the disclosure may cause.

Life claims data and legacy

APRA has spoken a number of times about the need to address the issues caused by legacy issues within the life insurance industry (that is, aspects of their operations that are no longer current, but remain in place as a legacy of earlier market conditions and practices). Legacy systems, processes and products are contributing to the problems experienced by insurers in providing credible, reliable and comparable data to support this data collection and other similar collections. Making the improvements necessary to support this data collection will require investment on the part of insurers but should improve the ability of insurers to respond to changing external demands and support management of the business.

Ultimately, this project has the potential to make lasting improvements to the life insurance industry, with both consumers and insurers benefitting from a more accountable, transparent and accessible market.

1 https://www.apra.gov.au/life-claims-data-collection

2 http://asic.gov.au/regulatory-resources/find-a-document/reports/rep-498-life-insurance-claims-an-industry-review/

3 March 2017 – PWC ‘Future of Life Insurance’